The one lesson I can best take away from some of my recent readings is that I should let things simmer for a while before giving a rating. The usual Julie-knee-jerk reaction hasn't been working well, as is evidenced by this one. When I closed the book on it last night, I thought, that was a very good book; yet when I came to pen these lines this morning, I had to say, that was an exceptionally good book -- from which I took away many important things, not the least of which is how to read differently. So, overnight, it soared from 4 to 5 stars, hitting its zenith while working its sinuous way deep into my psyche while I slept.

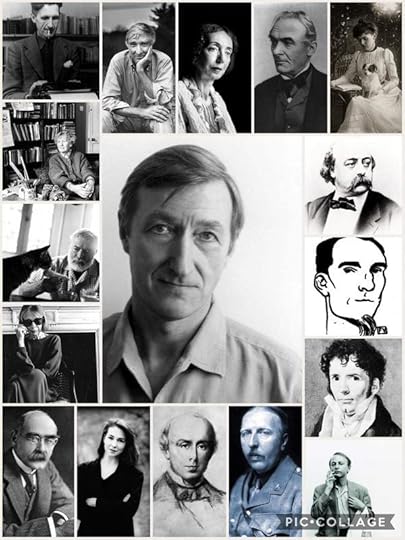

I knew Barnes was my-kind-of-writer by his opening sentence: I have lived in books, for books, by and with books; That's all I needed to read before I settled that I was his-kind-of-reader. In the most understated fashion, the preface is an ode to the written word -- an absolutely exquisite long paragraph of affirmations of bookdom, bookhood, bookness. And so the epode comes:

The American writer and dilettante Logan Pearsall Smith once said: "Some people think that life is the thing, but I prefer reading." When I first came across this, I thought it witty; now I find it -- as I do many aphorisms -- a slick untruth. Life and reading are not separate activities. The distinction is false (as it is when Yeats imagines the writer's choice between 'perfection of the life, or of the work'). When you read a great book you don't escape from life, you plunge deeper into it. There may be a superficial escape -- into different countries, mores, speech patterns -- but what you are essentially doing is furthering your understanding of life's subtleties, paradoxes, joys, pains, and truths. Reading and life are not separate but symbiotic. And for this self-discovery, there is and remains one perfect symbol: the printed book.

With such an auspicious start, I was horrified that his first essay should be on the perceptiveness of Penelope Fitzgerald. I groaned inwardly and thought I just might skip that one. (Admittedly, the only P Fitz I've read is Offshore, but that was seemingly enough to scar me for life, and which I put in my execrable list here on GR.) What a surprise to find that P Fitz is not at all who I thought her to be, based on my one reading experience. (I will not comment further on the humour, or irony, of that statement.)

Quite apart from her writing, Fitzgerald sounds like the kind of woman I would have liked to have had over for tea, discussing all manner of things; and in the end, she sounds so much more perceptive about life than I could have ever imagined. In effect, she is my-kind-writer, judging by Barnes's essay. Why did I hate her so much? Did I have my blinkers on that day? Was it an anti-P-Fitz kind of day? ... for certainly, I have those. Just like Eeyore, I have my anti days, in which everything is bleak and everything is execrable.

I pride myself on being perceptive and open minded about the books I read, but it seems not quite as much as I thought. [And of course, we all know what happens when pride comes into the picture. You tend to fall and twist your ankle on the cobblestones.] Since Barnes could presumably read my mind on the idea of 'bookdom', in his preface, I gave him the benefit of acquired knowledge and determined that I should give P Fitz another try. From his point of view, she is positively delightful. I'll have to find out how I could have been so wrong.

My mental re-alignment made this book a joy to get through. It's almost like he knew P Fitz would be my stumbling block; as if he were saying, If I can get through to her on this one, the rest is smooth sailing. And it was. For I connected with him absolutely on Clough and Orwell; on FMF and Kipling; on the art of translation and on Wharton and Updike. Others I didn't know like Fénéon and Moore. Chamfort is tangential and Houllebecq doesn't interest me in the least, but that's only a minor digression. And I recognized, just like Barnes did, the importance and magic of Hemingway's shorter fiction.

Throughout these essays, I was recognizing the touchstones of my life, and measuring them against what Barnes was saying. I was realizing that Barnes was quite a perceptive reader, and writer, much like the afore-mentioned P Fitz, whom I had avoided for no other reason than perhaps it was an Eeyore kind of reading day.

After reading The Sense of an Ending for instance, I had avoided him even though, quite unlike P Fitz's rating of execrable, I had given him four glowing stars for his novel. What I had found problematic with his work was that it said nothing -- absolutely nothing -- to me, but that he wrote beautifully. What was the value in that? So, I gave him 4 happy stars and went merrily on my way, not thinking about him again.

But it turns out that Barnes has indeed a lot to say:

Novels are like cities: some are organised and laid out with the colour-coded clarity of public transport maps, with each chapter marking a progress from one station to the next, until all the characters have been successully carried to their thematic terminus. Others, the subtler, wiser ones, offer no such immediately readable route maps. Instead of a journey through the city, they throw you into the city itself, and life itself: you are expected to find your own way. ... Such novels are not difficult to read, since they are so filled with detail and incident and the movement of life, but they are sometimes diffiuclt to work out. This is because the absentee author has the confidence to presume that the reader might be as subtle and intelligent as [she] is.

Perhaps I have been too used to reading those novels with the "readable routes". (One of my favourite souvenirs from my travels still remains the colourful London Tube map from the early 90s, for its depiction of transportation-nirvana.) Perhaps I'm not used to immersing myself in the "little nothings" of such novels, which in the end are the "little nothings" which make up the bigger part of life.

I'm not being coy or saying I don't understand those novels, and gee-whiz what a dunderhead I am; I'm simply saying that too often, I dismiss them with an almost contrived stubbornness, because they are too simple in presentation. There is that pride sneaking in again, that says, "Pshaw, I already know this. And someone has written an entire novel about it. Well, what a waste of time that was." When I should be saying ... Ah, stop for a moment, and listen to your heart beat. The rhythm is beautiful. Its simplicity is obvious ... but my god, isn't it magnificent?"

All this and more can be gleaned, through Mr. Barnes's window.