What do you think?

Rate this book

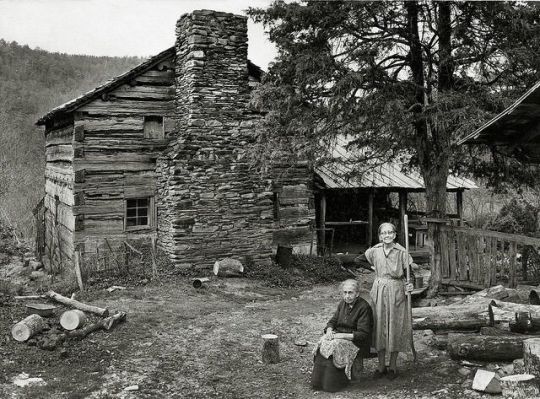

In Backwoods Witchcraft, Jake Richards offers up a folksy stew of family stories, lore, omens, rituals, and conjure crafts that he learned from his great-grandmother, his grandmother, and his grandfather, a Baptist minister who Jake remembers could "rid someone of a fever with an egg or stop up the blood in a wound." The witchcraft practiced in Appalachia is very much a folk magic of place, a tradition that honors the seen and unseen beings that inhabit the land as well as the soil, roots, and plant life.

The materials and tools used in Appalachia witchcraft are readily available from the land. This "grounded approach" will be of keen interest to witches and conjure folk regardless of where they live. Readers will be guided in how to build relationships with the spirits and other beings that dwell around them and how to use the materials and tools that are readily available on the land where one lives.

This book also provides instructions on how to create a working space and altar and make conjure oils and powders. A wide array of tried-and-true formulas are also offered for creating wealth, protecting one from gossip, spiritual cleansing, and more.

227 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 2019

Author Jake Richards has illuminated a remote and mostly hidden corner of Appalachian hill culture in this volume. Here is his premise for his book Backwoods Witchcraft: Conjure & Folk Magic From Appalachia: “We have our own way of faith, food, dress, music, and magic. We have our own lands and hills and trails….and it’s all ours, all that we can see. We may not be proud of some things, but that doesn’t mean we’ll divorce it. From our struggles and problems to our faith and culture, this is Appalachia. We are Appalachia.

“This culture relied on folk magic and medicine for centuries, when nary a preacher or doctor could be found. It lifted and placed curses, healed wounds inside and out, gave faith and hope to people, and, most importantly, endured. But this tradition is at a crossroads: live on or pass on. Either this work continues and lives, or it gets forgotten and breaks down more over time with each passing generation until the heirs of Appalachia have never seen the magic and faith of their forefolks.” (Jake Richards, Backwoods Witchcraft, p. 206).

I have great respect for any person’s chosen religious beliefs. Having been raised in a family of evangelical protestants, far be it from me to cast aspersions on anyone else’s beliefs.

But I have to draw a distinction between religious beliefs and superstition. When one discards the dogma of twenty-first century organized religion, I find little to distinguish between modern religious beliefs and practices and pure superstition. There’s not that much difference between the rites and rituals of twenty-first-century organized religion and the steps that Jake Richards recites as being required to invoke or dissolve “spells or curses” by Appalachian mountaineers. Indeed, there is no practical difference between the (Christian) ritual involved in the serving of “the Holy eucharist” (aka “The Lord’s Supper”), which is ceremoniously waved about, broken into bits, and then distributed to a select and highly exclusionary group of believers (one can share the Eucharist only if the supplicant has previously performed the rituals and repeated the particular words (spells) prescribed by the particular sect to be declared eligible to participate by the church authority) and the backwoods conjure ritual to “remove ill luck” (“[W]ash your current change of clothes with salt and vinegar and then burn them. Take the ashes to a crossroads at midnight and scatter them when the wind blows. Leave without looking back and go a different way home than you came…I recommend going to a crossroads far from your home.”) (p.194).

It’s hard for me to keep a straight face when I hear a Christian, a Muslim, a Jew, or any other type of believer struggles to distinguish between his particular chosen form of religious ritual and worship versus what Jake Richards describes as “Appalachian conjure and witchcraft.” It is enlightening to witness a proselytizer’s discomfit as he struggles to explain that, while his own personal beliefs are holy and special, the beliefs of others (in folk magic or any other type of religious ritual) are superstitious hokum.

With that said, I have little praise to offer Jake Richards’ book Backwoods Witchcraft: Conjure & Folk Magic From Appalachia.

I live, and have lived for most of my life on the side of a mountain in East Tennessee. That’s located in the dead center of the heart of Appalachian hill country.

It is widely understood that there are countless plant and animal compounds that source useful medicines. But I’ve never met anyone - anyone - in this neck of the woods who believes that folk magic is anything other than an amusing relic from a time before modern medicine was accessible among the remote and largely inaccessible hill communities. Indeed, a reading of the spells and curses which author Jake Richards recites from his hill-folk ancestors demonstrates that there are two different kinds of advice interspersed among his granny-woman’s old notes and records: those rooted in science, and those based upon superstitious beliefs.

Some of the advice of hill-folk root doctors is firmly based in science. Indeed, midwives/granny women/root doctors were unquestionably the best and most knowledgeable sources of medical knowledge available as to the healing powers of plants and natural resources. For example, the book’s section which is subtitled “Folk Recipes and Remedies” recites the following recommended treatment for sores and wounds: “For sore hands or feet, soak them in vinegar, salt, and warm water for thirty minutes.” (p.201). Well duh. This treatment is obviously a primitive antiseptic bath, and it is still perhaps as good a remedy for treating sores or wounds as any remedy that modern medicine has uncovered.

But note this: the book’s same section of remedies includes less practical treatment options for other ailments. Here’s what the author’s research recites as the treatment for bedwetting: “Place a Bible beneath the bed while saying, “In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, as the waters of Jordan stood, so shall the waters of (name).”

To treat sleepwalking, “...place a Bible at the head of the bed and a bucket of water at the foot.”

My favorite treatment in this whole book is the one offered to attract a lover: “For new love, give them wine or whiskey in which you’ve soaked your toenails for three days, from Wednesday to Friday. Strain it on Saturday morning. This will win over anyone.” (p.196).

I was especially interested in the author’s remedies for legal problems. Jake Richard’s family was either a litigious bunch or else the family tree was full of miscreants. I state this based on the numerous entries on spells to evoke favorable treatment in a courtroom. For instance, the author suggests eating the root of the Trillium plant to “keep the law away”: “Also known as Little John or Low John, trillium root was chewed the morning one had to go to court to gain favor with the judge. Harvest the roots in the Spring on a Friday, and hang them up in a bundle to dry, to keep the law away. You’ll need to feed them every month by dabbing whiskey on each stem while saying your prayers.”(p.169)

Fortunately, if for some reason eating trillium root did not keep the sheriff far away, the book offers a method to invoke special protection in case one had to appear before a judge: “Carry items for good luck when going to court, such as a peepstone, four-leaf clover, etc. You can also sprinkle salt in your shoes to make you “slicker than glass” so you’ll get by just fine. According to my mother, you should also take a toothbrush and a change of solid white clothes. This prevents you from going to jail because you’re already prepared.” (p.195).

The author even includes a chapter on the types of tools and supplies needed to work this magic. Some of the purposes for the tools listed make perfect sense. For instance, the author’s prescribed list of tools include a shovel (which makes it easier to dig) and a pair of gloves (for protection from getting stuck on plants with thorns, such as roses or thistle blooms).

However, not all of the uses for specific tools seem quite as efficacious. The author’s next recommended tool is a knife. Here is his first recited reason as to why a knife is a necessary tool: “When a bad storm is approaching, go to the south side of the house and drive the hilt of a knife into the ground with the blade pointing up and facing away from the house. This is said to cut the storm or tornado in half.” (pp.140-141).

One of my favorite book series was the Foxfire Book series by Elliot Wigginton and the students at tiny Rabun Gap High School deep in remote Appalachia. Several of the Foxfire books contained sections that more cover the same ground on the subject of folk medicine and folk magic that Jake Richards has undertaken in Backwoods Witchcraft: Conjure & Folk Magic From Appalachia. But there are two distinct differences: (1) Foxfire published this information forty years before Jake Richards took up the subject; and (2) Foxfire presents much if not most of the folk remedies as quaintly colorful but wholly ineffective, while Backwoods Witchcraft counts the same remedies as a useful part of the practitioner’s tool kit.

And I must say in conclusion that I’m highly skeptical about the efficacy of seducing another person by steeping one’s toenail clippings in a potion you then serve to your beloved, especially if the strainer used to remove the toenails lets one slip through.

This review took longer than usual for me to write, for it took me longer to process. I guess I’ll just call the book “thought provoking,” and I’ll be done with it.

My rating: 7/10, finished 6/22/22. (3653).