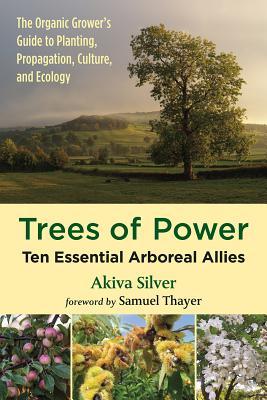

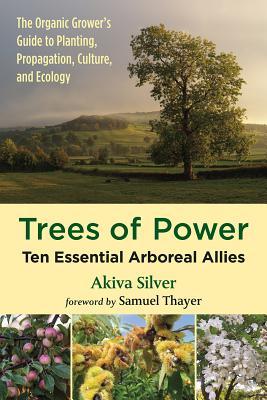

If the world could be changed through sheer enthusiasm, Akiva Silver would have transformed it already. Of course he has changed his corner of the world. He runs a tree nursery in Upstate New York where he plants trees, sells trees, harvests fruits and nuts for sale. But he envisions so much more: a world where trees are valued everywhere, where trees and humans are partners, where trees rain down bushels of fruits and nuts with less labor and fewer pesticides than are required for annual monocultures. The soil will be held in place, and not lost to erosion as happens with annual tilling of crops. Carbon will be sunk into the ground. Livestock will graze under the trees, eating fallen nuts and leaves. Butterflies and bees and birds will flourish. Children will play in the shade.

This is both a practical and a spiritual vision. On a spiritual plane he urges us to acknowledge that humans and trees, and likewise all plants and animals, are all joined together in the great thing called life, we are all leaves on the same tree, fingers on the same hand. On a practical basis, he recognizes that everyone has to eat and make a living. He constantly offers ideas for ways a person can use trees as a source of income. And he offers very detailed instructions for how to cut a graft, how to overwinter seeds without them getting moldy, how to keep birds and rodents from eating your seedlings.

The book begins with a philosophical (yet practical) introduction explaining how he came to be the tree person he is, how he believes that trees are sentient beings, and they respond to us as we help them. He also addressed the issue of environmentalist burnout. With so many complex problems facing our world, how do people who love nature keep from being depressed? After all, we can’t solve everything. For Silver, hope comes with just getting busy doing the work. He would rather be outdoors with the trees than writing grant proposals or lobbying governments.

The next section of the book is the how-to section. How to run a tree nursery. How to improve the soil with swales and berms. Scarification and stratification of seeds. Air pruning of roots. How close together to plant. Layering, grafting, coppicing, mulching, mowing, providing pollinators, discouraging voles. If you don’t plan to propagate your own trees, you will probably zone out during some of this. If you do, it will be a gold mine of information.

The next section lists his choice of ten trees that he considers some of the most beneficial. (The ten trees are chestnut, apple, poplar, ash, mulberry, elderberry, hickory, hazelnut, black locust, and beech.) For each tree he lists their good points and their limitations. He describes some of the varieties available, and the strengths and weaknesses of each. He tells what diseases and pests are a problem, and how to manage them. He tells about their history, and his experience with each, and all the possible good uses they could be put to, and their potential for the future. And get ready for the superlatives: the most generous fruit-giver, the best firewood in the history of firewood, the greatest magnet for all kinds of wildlife.

Silver is a man in love, and a man on fire with optimism. Hickory nuts may be hard to shell, but someone can come up with a machine. We can do it, if we just give it more attention. This enthusiasm is infectious. With every tree Silver described, I thought, yeah, I gotta get one of those (or two, or three, for pollination). I also enjoyed the times he was testy bordering on snarky, like when he complained about mulberry trees that were bred to be sterile, fruitless males. He said, “Sometimes I just don’t understand people. Why would anyone want a mulberry that doesn’t make fruit? That would be like having a car that doesn’t drive, or a pen that doesn’t write.” Silver’s opinions are not always the same as the prevailing wisdom. For instance, with trees such as the chestnut or ash, which are threatened with extinction because of disease, we should not plant less of them, but we should plant more, because that is how we may discover the disease resistant ones. And about black locust, he says that many people hate them, and some governments ban them as invasive, he said they don’t crowd out other species, but restore degraded land to fertile soil so that other hardwoods can flourish there again, and also black locust lumber is always in hot demand because of its durability.

But I could go on and on, and that’s probably enough. I should go out and plant something now.