What do you think?

Rate this book

485 pages, Hardcover

First published February 5, 2019

It was only logical that there were also Catholic and non-Catholic pudenda. Although Adrian had got out of the habit of thinking of such things, he allowed himself to distinguish briefly between a modest shrinking Catholic kind and another kind that was somehow a little the worse for wear.

‘There are three vows – poverty, chastity and obedience. Their purpose is to perfect a man spiritually.’ Adrian was embarrassed, but he offered up his discomfort to God and told himself he was acquiring the virtue of humility.

The doctor said, ‘Poverty and obedience too? They drive a hard bargain, don’t they?’

The last of his three temptations had been his scheme for a life of debauchery beginning with his pursuit of female students at Melbourne University. The trouble had started on the beach when Adrian was doing his best to guard his eyes.

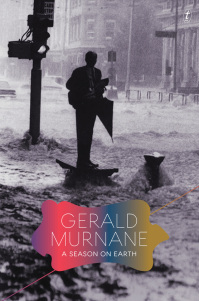

The image on the cover of Gerald Murnane's A Season on Earth is immediately recognisable to Melburnians of a certain age. A quick Google search reveals its provenance: the photo is by Neville Bowler from The Age newspaper in 1972 when the CBD in flood was front page news. Chosen by the inimitable W H Chong for the cover image, this photo of a man alone, stranded high and dry yet apparently calm, is just perfect for this book...

The image on the cover of Gerald Murnane's A Season on Earth is immediately recognisable to Melburnians of a certain age. A quick Google search reveals its provenance: the photo is by Neville Bowler from The Age newspaper in 1972 when the CBD in flood was front page news. Chosen by the inimitable W H Chong for the cover image, this photo of a man alone, stranded high and dry yet apparently calm, is just perfect for this book... As Murnane explains in the introduction, A Season on Earth has history. It was originally published in 1976 as A Lifetime on Clouds by Heinemann – in truncated form with just two of the four sections from the original manuscript. Indeed this the form in which I bought the 2013 Text Classics edition at the Boyd Community Library in Southbank. I had gone to hear Murnane in conversation with Andy Griffith, who wrote the introduction. (Although the book is now available in its entirety, I shan't be jettisoning A Lifetime on Clouds because I like the introduction. And I wish I'd asked Murnane to autograph it when I had the chance!)

As Murnane explains in the introduction, A Season on Earth has history. It was originally published in 1976 as A Lifetime on Clouds by Heinemann – in truncated form with just two of the four sections from the original manuscript. Indeed this the form in which I bought the 2013 Text Classics edition at the Boyd Community Library in Southbank. I had gone to hear Murnane in conversation with Andy Griffith, who wrote the introduction. (Although the book is now available in its entirety, I shan't be jettisoning A Lifetime on Clouds because I like the introduction. And I wish I'd asked Murnane to autograph it when I had the chance!)‘Reading Murnane, one cares less about what is happening in the story and more about what one is thinking about as one reads. The effect of his writing is to induce images in the reader’s own mind, and to hold the reader inside a world in which the reader is at every turn encouraged to turn his or her attention to those fast flocking images.’

After he had set the table for tea, Adrian read the sporting pages of The Argus and then glanced through the front pages for the cheesecake picture that was always somewhere among the important news. It was usually a photograph of a young woman in bathers leaning far forward and smiling at the camera.

If the woman was an American film star he studied her carefully. He was always looking for photogenic starlets to play small roles in his American adventures.

If she was only a young Australian woman he read the caption ('Attractive Julie Starr found Melbourne's autumn sunshine too tempting to resist. The breeze was chilly, but Julie, a telephonist aged eighteen, braved the shallows at Elwood in her lunch hour and brought back memories of summer') and spent a few minutes trying to work out the size and shape of her breasts. Then he folded up the paper and forgot about her. He wanted no Melbourne typists and telephonists on his American journeys. He would feel uncomfortable if he saw on the train one morning some woman who had shared his American secrets only the night before. (p.16)