What do you think?

Rate this book

186 pages, Paperback

First published October 23, 2018

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000...

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000...

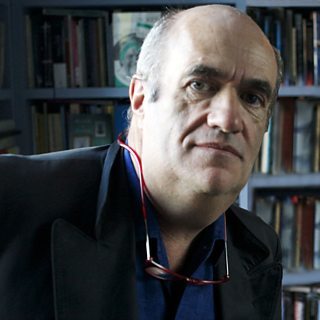

1/5: In today's episode Tóibín takes a literary walk around Dublin, stopping off at a variety of landmarks immortalised in the works of some of Ireland's most famous writers. At the same time he reflects on his own writing life.

1/5: In today's episode Tóibín takes a literary walk around Dublin, stopping off at a variety of landmarks immortalised in the works of some of Ireland's most famous writers. At the same time he reflects on his own writing life. 2/5: Tóibín is in Oscar Wilde's cell at Reading gaol where he is reflecting on the life and influence of William Wilde, the great writer's father.

2/5: Tóibín is in Oscar Wilde's cell at Reading gaol where he is reflecting on the life and influence of William Wilde, the great writer's father. 3/5: William Wilde is engulfed in a court case which, strangely, foreshadows the famous trial which had such devastating consequences for his son, Oscar, some thirty years later.

3/5: William Wilde is engulfed in a court case which, strangely, foreshadows the famous trial which had such devastating consequences for his son, Oscar, some thirty years later. 4/5: Tóibín's gaze turns to John B. Yeats, father of the literary giant, W.B. Yeats. It turns out that the brilliant conversationalist and impoverished artist was a source of exasperation, but also of inspiration to his son, and here Tóibín tells us why.

4/5: Tóibín's gaze turns to John B. Yeats, father of the literary giant, W.B. Yeats. It turns out that the brilliant conversationalist and impoverished artist was a source of exasperation, but also of inspiration to his son, and here Tóibín tells us why. 5/5: Tóibín turns to the romantic and occasionally erotic correspondence between John B. Yeats and Rosa Butt, when the pair were in their sixties. He then reflects on the influence that the father's boyish romance had on the writings of his son, the literary giant W. B. Yeats.

5/5: Tóibín turns to the romantic and occasionally erotic correspondence between John B. Yeats and Rosa Butt, when the pair were in their sixties. He then reflects on the influence that the father's boyish romance had on the writings of his son, the literary giant W. B. Yeats. 1877 caricature of Queensberry in Vanity Fair.

1877 caricature of Queensberry in Vanity Fair.

My father was still in his early forties, a man who had received a university education and had never known a day’s illness. But though he had a large family of young children, he was quite unburdened by any sense of responsibility towards them. His pension, which could have taken in part the place of the property he had lost and been a substantial addition to an earned income, became his and our only means of subsistence. (p.166)

He is domineering and quarrelsome and has in an unusual degree that low, voluble abusiveness characteristic of Cork people when drunk… He is lying and hypocritical. He regards himself as the victim of circumstances and pays himself with words. His will is dissipated and his intellect besotted, and he has become a crazy drunkard. He is spiteful like all drunkards who are thwarted, and invents the most cowardly insults that a scandalous mind and a naturally derisive tongue can suggest. (p. 167)

I was very fond of him always, being a sinner myself, and even liked his faults. Hundreds of pages and scores of characters in my books came from him… I got from him his portraits, a waistcoat, a good tenor voice, and an extravagant licentious disposition (out of which, however, the greater part of any talent I may have springs) but, apart from these, something else I cannot define. (p.173.)