#Binge Reviewing my previous Reads # Comics and Graphic Novels

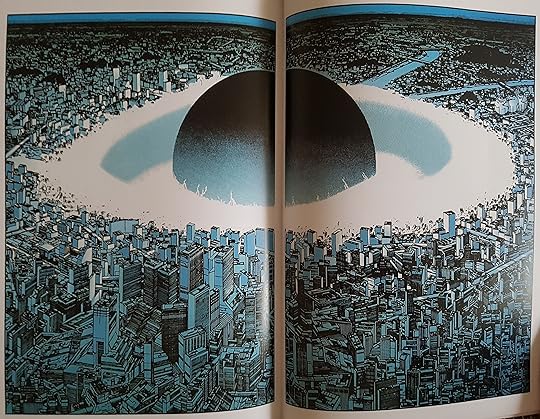

By the time you reach Akira, Vol. 3, you feel as though the Tokyo that once existed has completely vanished, not only physically but psychologically. Katsuhiro Otomo doesn’t just continue his story here; he detonates it, unleashing chaos on such a scale that it feels like the manga itself is mutating along with its characters. The aftermath of Akira’s psychic explosion dominates the volume — the ruined cityscape is no longer just a setting, but a character in itself, an enormous open wound upon which new mythologies, new hierarchies, and new nightmares are written. It is here that the narrative of Akira pivots from dystopian cyberpunk into something more apocalyptic and messianic, blurring the line between political allegory and metaphysical speculation.

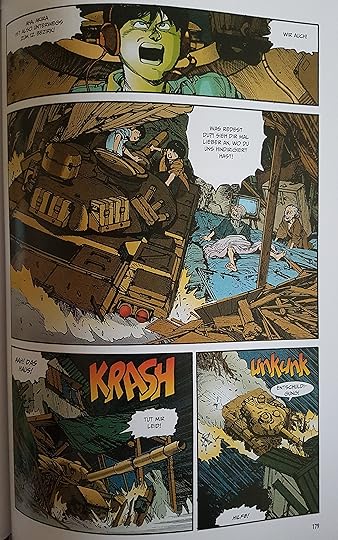

The power struggles that begin to crystallize in this volume are fascinating. Kaneda, always the brash and reckless punk, finds his narrative orbit increasingly pulled toward Tetsuo, who by now is becoming something beyond human. Their friendship, which started as a familiar delinquent camaraderie, is mutating into a cosmic rivalry, the kind of archetypal conflict that manga and myth thrive on. Tetsuo’s evolution — his physical body becoming unstable, his mind succumbing to bursts of incomprehensible psychic force — is both terrifying and strangely tragic. He’s a boy caught in a storm of power, and Otomo makes you feel the inevitability of his unraveling.

At the same time, the government and military remnants, desperately trying to contain the catastrophe, resemble rats scrambling across the wreckage of a sinking ship. Colonel Shikishima emerges here not merely as a soldier but as a complex figure, torn between his authoritarian instincts and his genuine concern for Akira and the children. He is one of the great paradoxes of Otomo’s cast: both ruthless and oddly paternal, capable of ordering mass destruction while at the same time showing tenderness toward the psychic children who embody both promise and doom.

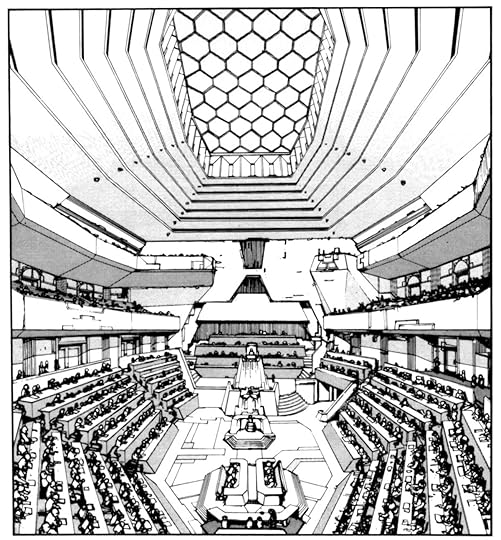

What makes Volume 3 especially powerful is how Otomo sharpens the thematic stakes. The narrative is no longer simply about biker gangs, government conspiracies, or even military corruption. It becomes a meditation on power itself: how it destabilizes the human body, how it corrodes institutions, how it reorders entire societies in its wake. Akira himself remains eerily silent throughout, an almost godlike void around which others project their hopes and fears. Religious cults form around him, treating the boy not as a weapon but as a messiah. This religious turn adds a chilling dimension to the story: Akira ceases to be about survival in a ruined city and instead becomes about the birth of a new order — and the terror that accompanies revelation.

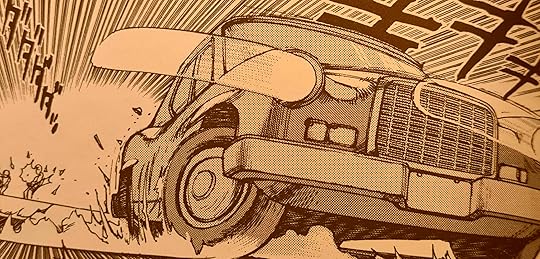

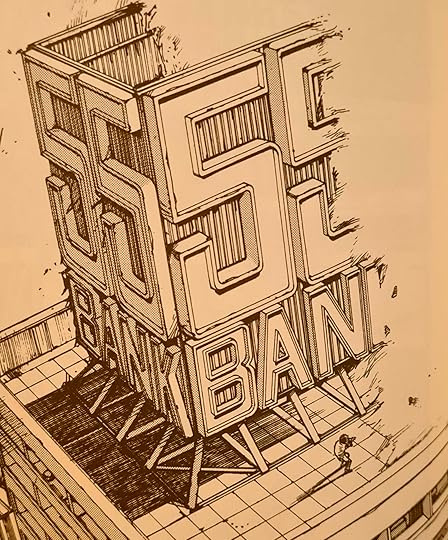

Visually, this volume is jaw-dropping. Otomo’s draftsmanship reaches new levels of density: the ruins of Neo-Tokyo are etched with obsessive detail, every collapsed building and twisted beam rendered with apocalyptic grandeur. His action sequences retain their kinetic brilliance, but it is the quiet panels — the children in their sterile rooms, the cultists gathering with their fanatical eyes, the shadows across Tetsuo’s increasingly grotesque form — that linger in the mind. Otomo is a master of pacing, alternating frenetic chaos with moments of eerie stillness, so that when violence erupts, it feels almost unbearable.

There’s also something very Japanese in this imagery, and very contemporary for the 1980s context in which Otomo was working. The shadow of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the trauma of nuclear devastation, the anxieties of the Cold War — all these pulse through the wreckage of Akira. But Otomo is not content with allegory. He pushes toward something mythic, situating Akira and Tetsuo in the lineage of apocalyptic figures from across cultures. They are both gods and demons, children and destroyers, symbols of uncontainable energy that could just as easily create a new world as annihilate the old.

In Kaneda’s swagger and refusal to bow to despair, one sees a stubborn, almost punk resilience — a refusal to let the world collapse into fatalism. But in Tetsuo, one sees the nightmare of unchecked desire, of the human will fused with power beyond comprehension. The two together dramatize the paradox of modernity: technology and energy that promise progress but threaten extinction, friendship and loyalty twisted into rivalry and destruction.

What’s particularly striking in this volume is how Otomo allows ambiguity to flourish. No one is entirely hero or villain here. The colonel, as mentioned, is both oppressor and protector. The children, for all their innocence, are also weapons of unimaginable destruction. Tetsuo is monstrous, but also pitiable. Even Kaneda’s loyalty has an undertone of recklessness that may doom everyone. The city itself is the perfect stage for this moral ambiguity: a wasteland where old structures have collapsed and new cults, new armies, new alliances are struggling to be born.

By the end of Vol. 3, one feels as though the narrative has entered an entirely new phase, no longer cyberpunk in the narrow sense but a cosmic, almost biblical saga. The reader is left both exhilarated and unsettled: what can possibly come after this? Otomo’s genius lies in making us feel the sheer scale of the world he’s building — the sense that this is not just the story of a gang or a city, but the story of humanity standing at the edge of its own mutation.

Akira, Vol. 3 is thus not simply a midpoint in a manga series; it is the place where Otomo’s masterpiece shifts from dystopian drama into apocalyptic myth. It asks questions that go beyond its setting: what happens when human power outstrips human morality? Can institutions or friendships survive the blast of godlike energy? Or is destruction the only possible future? These questions haunt every page, and the fact that they remain unanswered is precisely what makes the story so gripping.

Most recommended.