What do you think?

Rate this book

368 pages, Paperback

Published September 5, 2019

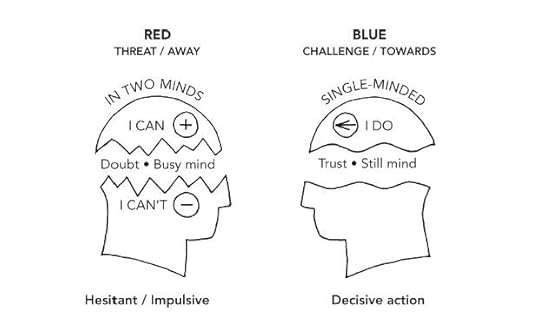

Here are 10 reasons why I strongly believe in the RED–BLUE mind model:

1. It works. It wouldn’t exist if people didn’t feel it had significantly helped them. (Nor would this book!)

2. I use it myself (all the time). My best and worst moments – as a parent, footballer, clinical director or speaker – all relate back to my use (or non-use) of the model in my own life.

3. It’s for all of us. I have seen the best in the world get mentally better – and worse – in different moments. I have also seen those in the mid-range, and those with everything against them, get mentally better – and worse – in different moments. Everyone is on the same RED–BLUE page.

4. It’s practical. I’ve met experts who know more about the theory behind the brain than I ever will, but just like the rest of us, they’re still held back in their performance when it comes to putting it into practice. No amount of theory can alter that.

5. It changes lives. It has encouraged people, time and again, to venture into more challenging areas, which have proved to be personally significant, and occasionally life-changing.

6. It provides balance. In every performance environment I’ve experienced there is an opportunity to be exceptional in the technical aspects of that field and the mental elements, but few are exceptional at both. Even in those fields seemingly ruled by technology, human elements still have their say – and often the final word.

7. It’s easy to use: People quickly pick up on the main RED–BLUE ideas and make them work, because the model is intuitive.

8. It works for young and old. I’m not an expert in child psychology, but (as you’ll see) ten year olds have picked up the model and run with it; and I’ve seen people of advanced age change their philosophy even after a lifetime of unhelpful mental habits.

9. It’s enjoyable. It takes what for many is an unwelcoming area – performing under pressure – and turns it into a personally relevant road map.

10. It surprises people. It surprises – and even shocks – experienced performers when they suddenly realise that they have been trying to ‘get better’ most of their lives by trying to become more comfortable when they perform, guided by an unspoken assumption that this is the only or best way forward. The idea that significant opportunity exists in the space of becoming more effective when they are uncomfortable can come as a revelation.