What do you think?

Rate this book

5 pages, Audiobook

First published January 1, 2015

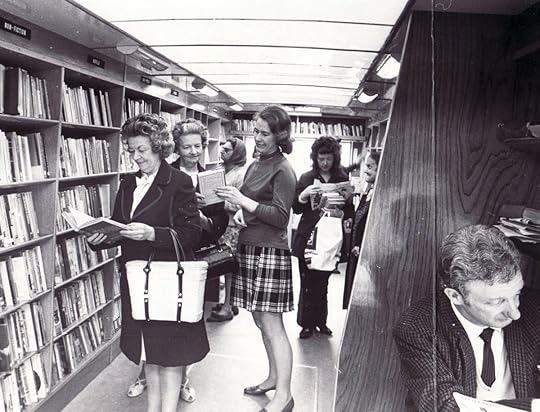

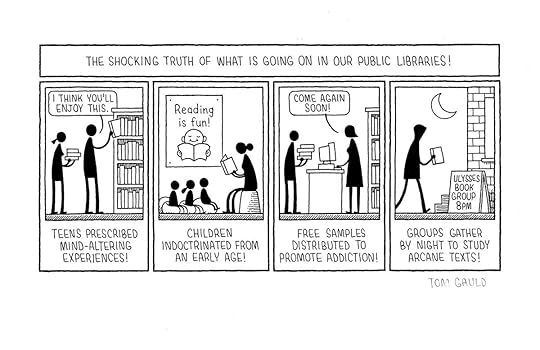

‘Libraries save the world. A lot, but outside the narrative mode of heroism: through contemplative action, anonymously and collectively. For me, the public library is the ideal model of society, the best possible shared space, a community of consent—an anarcho-cyndicalist collective where each person is pursuing their own aim….through the best possible medium of the transmission of ideas, feelings and knowledge: the book.’

Library

that beautiful new build

opened by mark twain

a clean, well-lighted place

the ideal model of society

soon to be sold

put a price on that

on bleak house road

curve tracing

the library sunlight

the making of me

the infinite possibilities

…a scheme where you got points for taking out books and when you reached a certain number of points the prize was that you got to help the librarian tidy up the shelves. We all wanted to do that.Shades of Tom Sawyer! Or this, which I think I can quote complete:

Miriam Toews told me about how once, a couple of years ago, when she will sitting reading at a desk in Toronto's public library, she saw her own mother come in and sit down in one of the sunlit seats by the windows. Her mother, without noticing her daughter there, settled down, stretched out and fell asleep.But what about Ali Smith's actual stories? I don't think I have read any short fiction from her before, only the novels How to Be Both and The Accidental, both of which I enjoyed a lot, so I didn't know what to expect. Only these didn't seem to be normal stories, so much as scattered pages of a memoir about the writing life, almost all in the first person. Of course, I know that the "I" in the story is not necessarily I, Ali Smith, the writer; indeed there were one or two where clearly the I was male. But there is a kind of loose consistency between the various I's: born in Inverness, educated at Cambridge, partnered then separated, possibly partnered again.

She sat where she was and watched her mother sleep.

A library assistant approached her mother. She saw this assistant reach out a tentative hand and give her mother a shake.

Her mother didn't wake up.

The assistant stepped back, stood as if thinking about it for a moment, then left her mother sleeping in the library sunlight.

I'd been reading him since I was sixteen, when I chose a dual copy of St. Mawr / The Virgin and the Gypsy for a school prize, mostly because I knew if would discomfit the Provost and his wife, who annually gave out the prizes; Lawrence was still reasonably notorious in Inverness in the 1970s. (It makes me laugh even now that the prize sticker inside my paperback says I'm being awarded for Oral French.)Then there is her interest in language. "Last," a story about a rescuing a wheelchair-bound woman marooned on a train that has been shunted into a siding, is constantly interrupted by musings on the changing meanings of words. "Good Voice" starts as a piece about disappearing regional accents, then turns into a stream-of-consciousness cocktail of phrases from WW1 poetry. "And So On," a commissioned piece for a collection on the theme of death, contains an amusing anecdote about a trip to Greece with a friend who kept getting strange looks for people when she asked the way to the sea. If modern Greek is anything like the ancient variety, it would be easy to understand how the friend might confuse "thalassa," the word for sea, with "thanatos," the word for death.

He is most famous, it says here, for his poems about girls, love, spring, flowers. Fair daffodils, we weep to see / ye haste away so soon. Then, then, methinks, how sweetly flows / That liquefaction of her clothes. How Roses Came Red. To a Bed of Tulips. To Violets. To Meadows. To Primroses Filled with Morning Dew. To Daisies, Not to Shut so Soon.And then the way she ends:

I'd fill every toaster that ever stopped working, got thrown out, got buried in landfill. I'd fill all their slots with wild colours and flowerheads. I'd fill that old shop with the smell of this earth.=======