What do you think?

Rate this book

368 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2002

Denying [CP]…will allow the passage of laws getting them out of undue influence in politics…Federal, State and local governments will be able to enforce laws, if the citizens want, that require corporations to operate to the benefit of the states and the communities in which they are incorporated and do business.Not sure of every aspect of that but it is certainly an intriguing concept and one that I think warrants further discussion. It certainly seems like it might be very worthwhile as long as it applies equally to trade unions and other associations.

That war- finally triggered by a transnational corporation and its government patrons trying to deny American colonists a fair and competitive local marketplace-would last until 1783This is a ridiculous statement. The East India Trading Company WAS the British Government. This was not a company using its influence to get the British Government to make decisions on its behalf. It was the British Government making decisions that benefited itself and using the East India Trading Company as a vehicle because the King and almost every member of Parliament was a shareholder in the company.

Let me explain to you how this works: you see, the corporations finance Team America, and then Team America goes out... and the corporations sit there in their... in their corporation buildings, and... and, and see, they're all corporation-y... and they make money.Much of it does indeed come across as the kind of crude anti-right, anti-corporate propaganda cleverly satirized by Trey Parker and Matt Stone. In the background, though, I could hear the young Joan Baez singing a verse from All My Trials:

If living were a thing that money could buyThe book may be unsubtle anti-corporate propaganda; but most of it, I fear, is true.

You know the rich would live, and the poor would die.

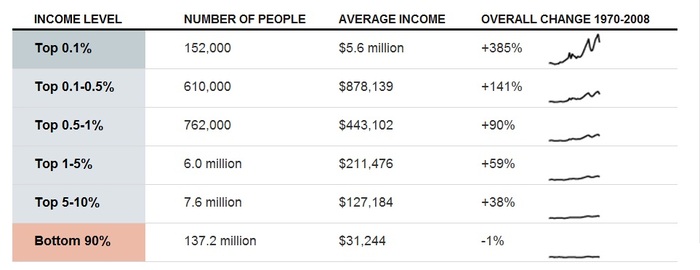

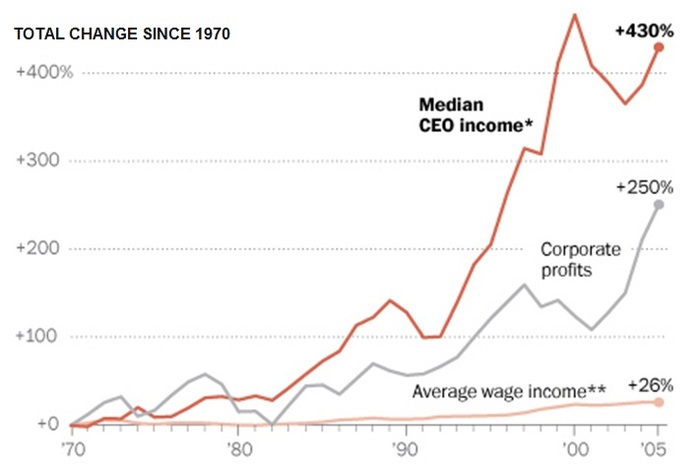

…extremes of wealth can unfairly reduce the economic opportunities and political rights of everyone else, according to sociologists. The wealthy, for example, can afford better private schools for their children or acquire political might by purchasing campaign advertising or making campaign donations.Now, you might want to say that, yeah, these people are smart, they work hard yadda yadda yadda. So, they deserve what they make. Fair enough. But do they deserve to see their salaries go up by 4 times when corporate profits have only gone up by 2.5 times?

…

In world rankings of income inequality, the United States now falls among some of the world’s less-developed economies.… According to the CIA’s World Factbook, which uses the so-called “Gini coefficient,” a common economic indicator of inequality, the United States ranks as far more unequal than the European Union and the United Kingdom. The United States is in the company of developing countries—just behind Cameroon and Ivory Coast and just ahead of Uganda and Jamaica.

…

…late last year, economists Bakija, Cole and Heim completed their massive analysis of income tax returns. Little noticed outside academic circles, their research focused on the top 0.1 percent of earners. From those tax returns, they could glean a taxpayer’s occupation, which is self-reported. Using the employer’s tax identification number, the researchers found the industry they were employed in.

…

“Basically, executives represent a much bigger share of the top incomes than a lot of people had thought,” said Bakija, a professor at Williams College, who with his co-authors is continuing the research. “Before, we just didn’t know who these people were.”

The prevalence of the corporation in America has led men of this generation to act, at times, as if the privilege of doing business in corporate form were inherent in the citizen; and has led them to accept the evils attendant upon the free and unrestricted use of the corporate mechanism as if these evils were the inescapable price of civilized life, and, hence, to be borne with resignation.

Throughout the greater part of our history a different view prevailed.

Although the value of this instrumentality in commerce and industry was fully recognized, incorporation for business was commonly denied long after it had been freely granted for religious, educational, and charitable purposes.

It was denied because of fear. Fear of encroachment upon the liberties and opportunities of the individual. Fear of the subjection of labor to capital. Fear of monopoly. Fear that the absorption of capital by corporations, and their perpetual life, might bring evils similar to those which attended [immortality]. There was a sense of some insidious menace inherent in large aggregations of capital, particularly when held by corporations. 309