What do you think?

Rate this book

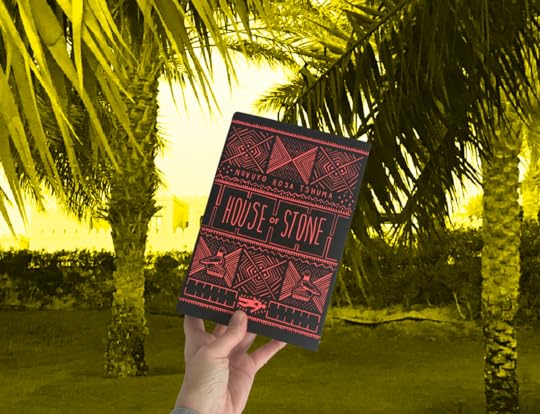

384 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2018

I’m the one who’s survived and he’s the one who’s disappeared, thanks to those mad antics of his. Poof! Like a spoko. He too was gobbled up by one of those police vans the day of the Mthwakzi rally, and has not been regurgitated since.

Like Bukhosi, I doubt I’ll ever see Dumo again. It was he who taught me that a man could remake himself by remaking his past. So when Abednego said I was like a son to him and that he would, from then on, call me his surrogate son, I felt a swell of pride and the prick of opportunity. Perhaps, as my surrogate father’s son, I can be blessed with sole familial affection and, in this way, finally powder away the horrors of my own murky hi-story bequeathed to me by parents I never knew.

Isn’t this the hi-story Bukhosi always wanted to know, before he went missing? For which he got a beating whenever he asked our father ‘Baba, what happened in the ’80s, what was the Gukurahundi?

That was the Gukurahundi, Bukhosi. It was the lead rain of our new country, Zimbabwe, sent to wash away us, the chaff. It was the state-sponsored murder of twenty thousand of your kin. How was our father to tell you that? How was he to tell you that within that number were the only two people he ever really loved?

“We speak about the Liberation War all the time. But when it comes to the genocide, it is always a matter of shutting it down,” she says, adding that by not addressing the psychological, social and communal issues, by not acknowledging people have died, healing cannot begin.

Did that Reverend Nobody really think he could take me on? Did he really think he could come out as the hero in all of this, mooching off my hard work, destroying my relations with my surrogate family.

“And now, the valour of our people and the glory of the Mthwakazi Nation lives on not in any history book, or in any official account, where we are nothing but savages without culture, without history or glory or anything worth mentioning or passing on,” she said, pressing her hand to her chest. “I heard the stories from my father, passed down to him by his father, my grandfather, and which I shall one day pass down to my children.” (p.53)

But Zamani does not know his lineage. He was brought up by Uncle Fani after the death of his mother, and the imposed collective silence about the atrocity in which she died means that he does not even know how she died, or more ominously, who his father was. Abed does not know who his father was either, and the suggestion that it might be a neighbouring white farmer sends him into alcoholic rages and violence against his wife Agnes. These people are emblematic of the way Zimbabwe’s violent pre- and post-colonial history is at odds with its ancient tribal traditions.

To read the rest of my review please visit https://anzlitlovers.com/2019/01/05/h...