What do you think?

Rate this book

256 pages, Mass Market Paperback

First published January 1, 1955

"Rumphius says that they're quite beautiful."

"Yes," said the officer, "a strange poisonous green, with long blue streamers, and the sails are sort of transparent with a coloured edge."

"A crystal sail edged with purple or violet."

"Yes," the officer agreed, a bit astonished.

"Like a jewel, Rumphius said."

"Yes," there was a flicker of enthusiasm in the blue eyes, "yes, that's true!"

Glorious, someone said.

And Suprapto continued, " I guess the sails aren't very big–"

"Now, how could they be big? Without the streamers these jellyfish aren't big themselves–the sails aren't bigger than–" the officer looked around for something to compare them with: his own firm hand, and then the slim dark hand which the Javanese held on his knee. He didn't touch it, but he pointed at it, his fingers moving under the knuckles, "a bit larger than the width of your hand perhaps."

Suprapto looked where the other had pointed–his own thin hand.

"Yes," he said in his even, toneless voice, "I realized that those sails are small–not big,"

For a short moment it caused him an almost inhuman pain.

She knew that a bay and rocks and trees bending over the surf cannot relieve sadness—can sadness be relieved, or can one only pass it by, very slowly?In my reading over the past decade, I have really come to trust the reissues of the New York Review of Books—works of fiction, predominantly foreign, that have undeservedly slipped out of circulation. They do for older literature what the Europa Press does for contemporary: open the reader's eyes to a wide range of geographical locations, subjects, and narrative approaches. There are many hits but few misses, and even the oddball books that are hard to classify are fascinating in their oddness.

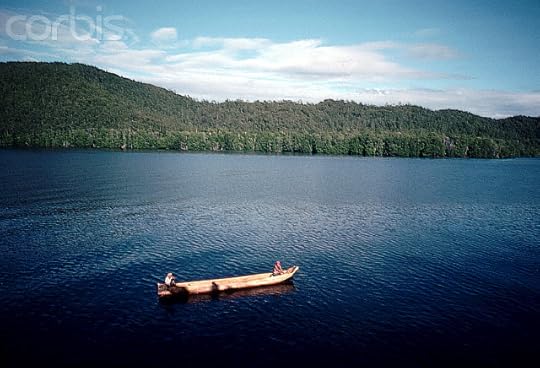

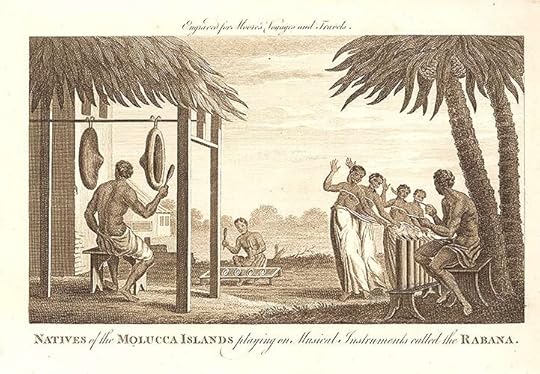

The Ten Thousand Things is a novel of shimmering strangeness—the story of Felicia, who returns with her baby son from Holland to the Spice Islands of Indonesia, to the house and garden that were her birthplace, over which her powerful grandmother still presides. There Felicia finds herself wedded to an uncanny and dangerous world, full of mystery and violence, where objects tell tales, the dead come and go, and the past is as potent as the present.