What do you think?

Rate this book

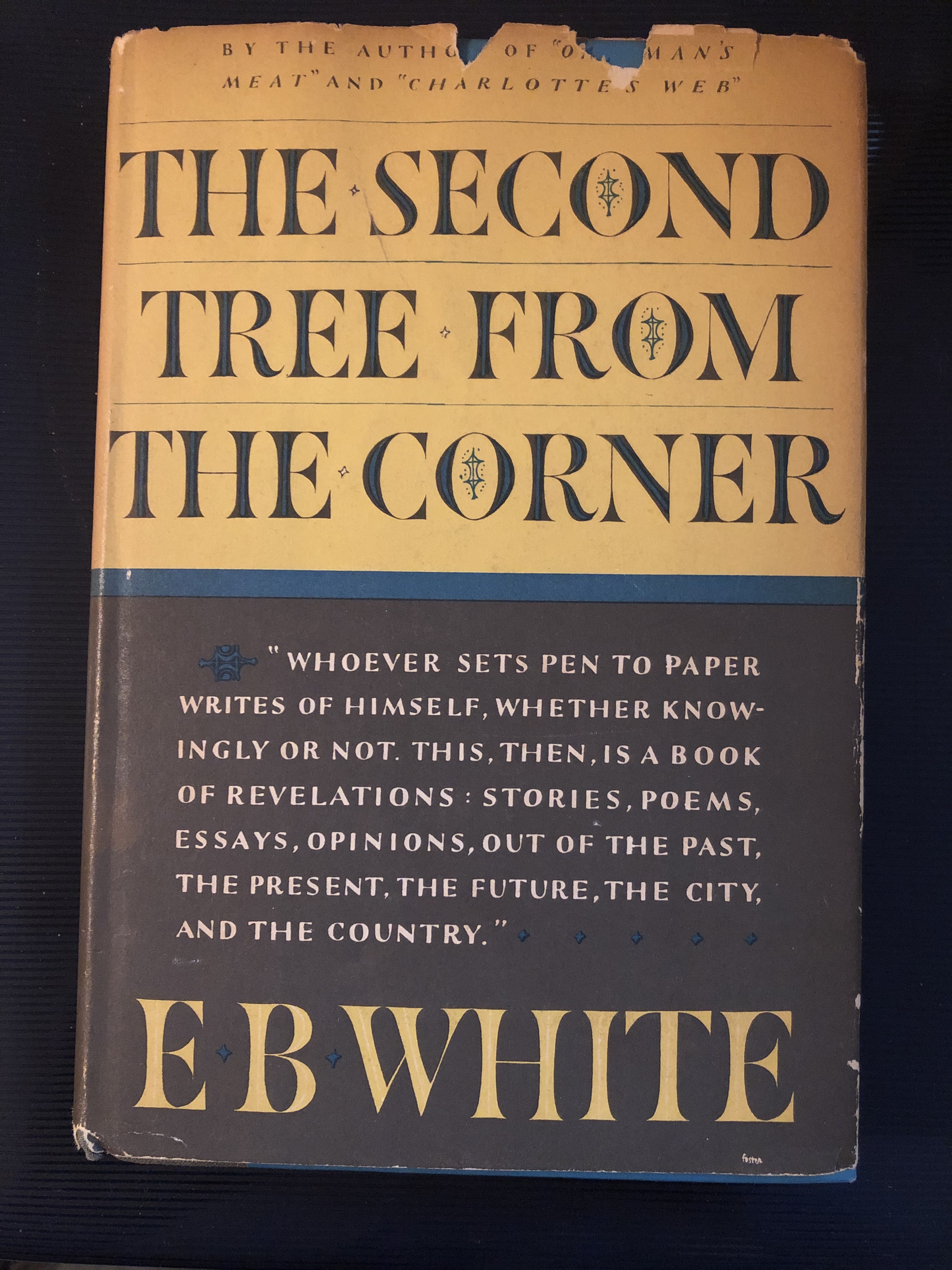

253 pages, Hardcover

First published January 28, 1954

L.D. writes: Is there any likelihood that the temporary physical condition a man is in would have an effect on his offspring? In other words, should a man hesitate about becoming a father during the time he is suffering from hay fever? - Health column in the Chicago Tribune.

This is a question many a man has had to face, alone with his God. Sensitivity to pollen, the male element of flowers, is at once an exalted and a pitiable condition and inevitably suggests to a prospective progenitor the disquieting potentialities inherent in all propagation. Like father like son is the familiar saying: big sneeze, little sneeze. There is little doubt that allergy to hay, so deep-seated, so shattering, is inheritable; and it is just as certain that a sensitive man, during the season of his great distress, is as eager for life and love as in the periods when his mucosae are relaxed. We cannot conscientiously advise any man to abstain from fatherhood on a seasonal, or foliage, basis. The time not to become a father is eighteen years before a world war.

The Newark police arrested a very interesting woman the other day - a Mrs Sophie Wienckus - and she is now on probation after being arraigned as disorderly. Mrs Wienckus interests us because her 'disorderliness' was simply her capacity to live a far more self-contained life that most of us can manage. The police complained that she was asleep in two empty cartons in a hallway. This was her preferred method of bedding down. All the clothes she possessed she had on - several layers of coats and sweaters. On her person were bankbooks showing that she was ahead of the game to the amount of $19,799.09. She was a working woman - a domestic - and, on the evidence, a thrifty one. Her fault, the Court held, was that she lacked a habitation.

'Why didn't you rent a room?' asked the magistrate. But he should have added parenthetically '(and the coat hangers in the closet and the cord that pulls the light and the dish that holds the soap and the mirror that conceals the cabinet where lives the aspirin that kills the pain).' Why didn't you rent a room '(with the rug that collects the dirt and the vacuum that sucks the dirt and the man that fixes the vacuum and the fringe that adorns the shade that dims the lamp and the desk that holds the bill for the installment on the television set that tells of the wars)?' We feel that the magistrate oversimplified his question.

Mrs Wienckus may be disorderly, but one pauses to wonder where the essential disorder really lies. All of us are instructed to seek hallways these days (except school children, who crawl under desks), [The US expectation of nuclear attack against them colours much of White's writing in this sort of way] and it was in a hallway that they found Mrs Wienckus, all compact. We read recently that the only hope of avoiding inflation is through ever increasing production of goods. This to us always a terrifying conception of the social order - a theory of the good life through accumulation of objects. We lean toward the order of Mrs Wienckus, who has eliminated everything except what she can conveniently carry, whose financial position is solid, and who can smile at Rufus Rastus Johnson Brown. We salute a woman whose affairs are in such excellent order in a world untidy beyond all believe.

The Dream of the American Male

Dorothy Lamour is the girl above all others desired by the men in Army camps. This fact was turned up by Life in a routine study of the unlimited national emergency. It is a fact which illuminates the war, the national dream, and our common unfulfillment. If you know what a soldier wants, you know what Man wants, for a soldier is young, sexually vigorous, and is caught in a line of work which leads towards a distant and tragic conclusion. He personifies Man. His dream of a woman can be said to be Everyman's dream of a woman. In desiring Lamour, obviously his longing is for a female creature encountered under primitive conditions and in a setting of great natural beauty and mystery. He does not want this woman to make any sudden or nervous movement. She should be in a glade, a swale, a grove, or a pool below a waterfall. This is the setting in which every American youth first encountered Miss Lamour. They were in a forest; she had walked slowly out of the pool and stood dripping in the ferns.

The dream of the American male is for a female who has an essential languor which is not laziness, who is unaccompanied except by himself, and who does not let him down. He desires a beautiful, but comprehensible, creature who does not destroy a perfect situation by forming a complete sentence. She is compounded of moonlight and shadows, and has a slightly husky voice, which she uses only in song or in an attempt to pick up a word or two that he teachers her. Her body, if concealed at all, is concealed by a water lily, a frond, a fern, a bit of moss, or by a sarong - which is a simple garment carrying the implicit promise that it will not long stay in place. For millions of years men everywhere have longed for Dorothy Lamour. Now in the final complexity of an age which has reached its highest expression in the instrument panel of a long-range bomber, it is a good idea to remember that Man's most persistent dream is of a forest pool and a girl coming out of it unashamed, walking toward him with a wary motion, childlike in her wonder, a girl exquisitely untroubled, as quiet and accommodating and beautiful as a young green tree. That's all he really wants. He sometimes wonders how this other stuff got in - the instrument panel, the night sky, the full load, the moment of exultation over the blackened city below....