One doesn't have to agree to all the theories he evokes, but he does point out interesting questions regarding our way of interpreting artworks.

questions raised :

est-ce que toutes les oeuvres à l'époque (avant le XXe siècle) avaient un but moralisant?

il y a toujours plusieurs façons d'interpréter une oeuvre...

fav quotes :

"comment se fait-il qu'au moment d'interpréter certaines oeuvres, nous puissions être aussi loin l'un de l'autre? Je ne prétends pas que les oeuvres n'auraient qu'un seul sens et qu'il n'y en aurait donc qu'une seule 'bonne' interprétation." (p.11)

"tu sembles à tout prix, à certains moments, vouloir interposer entre toi et l'oeuvre, une sorte de filtre solaire qui te protégerait de l'éclat de l'oeuvre et préserverait les habitudes acquises dans lesquelles se fonde et se reconnaît notre communauté académique." (p.11-12) ; il ne faudrait donc pas regarder une oeuvre en cherchant comment elle explique une théorie / une morale /etc

"Ce n'est pas parce que ces textes existent, ce n'est même pas parce qu'ils auraient été publiés en même temps que le tableau était peint qu'ils contribuent nécessairement à expliquer ce tableau. Ce serait trop simple. Il peut exister, au même moment dans une même société, des points de vue ou des attitudes contradictoires." (p.14)

"Tout ce qui est inhabituel n'est pas nécessairement allégorique. Ça peut être sophistiqué, paradoxal, parodique, je ne sais pas." (p.15)

"je n'ai pas eu besoin de textes pour voir ce qui se passe dans le tableau.[...] On dirait que tu pars des textes, que tu as besoin de textes pour interpréter les tableaux, comme si tu ne faisais confiance ni à ton regard pour voir, ni aux tableaux pour te montrer, d'eux-mêmes, ce que le peintre a voulu exprimer." (p.23) ; il critique ainsi la méthode employé par plusieurs historiens de l'art qui cherchent la représentation X dans les oeuvres à la fois de faire le contraire et observer puis analyser et comparer.

"il n'a laissé aucune trace dans les oeuvres d'artistes contemporains. Autrement dit, à peine peint, il disparaît de la circulation. Étonnant tout de même, pour un tableau d'un tel maître..." (p.25) ; a nouveau il souligne le fait qu'il faudrait penser au contexte de l'oeuvre, sa façon non seulement de création mais aussi son lieu d'exposition

"Je n'ai ni texte ni documents d'archives pour prouver ce que j'avance et, donc, ce n'est pas historiquement sérieux. Mais je crains, moi, que ce sérieux historique ne ressemble de plus en plus au "politiquement correct", et je pense qu'il faut se battre contre cette pensée dominante, prétenduement historienne, qui voudrait nous empêcher de penser et nous faire croire qu'il n'y a jamais eu de peintres "incorrects"." (p.26)

-x-

le regard de l'escargot

"il fallait qu'il pût y trouver un sens acceptable aux yeux de ses commanditaires - et de lui-même. Mais la savante n'a pas expliqué ce qu'il fait là, au tout premier plan du tableau, sous notre nez. Et pour cause : ce n'est pas le rôle de l'iconographie. Elle n'a pas à nous sire pourquoi le peintre l'a mis à cet endroit, ça échappe à ses compétences." (p.34)

"je ne crois pas non plus à la "géométrie secrète" des peintres. L'esprit de géométrie règne plus souvent chez l'interprète que chez l'artiste." (p.38) ; faudrait faire ainsi gaffe à la surinterprétation

"ça leur montrait qu'on peut réfléchir quand on regarde un tableau, et que réfléchir n'est pas nécessairement triste." (p.39)

"Il est sur son bord, à la limite entre son espace fictif et l'espace réel d'où nous le regardons." (p.42) ; il ne faut pas oublier que dans un tableau il y a toujours deux espaces à réfléchir sur car la peinture en soi est une surface plane représentative et qui évoque le geste créatif de l'artiste.

"il signale le lieu d'entrée de ce regard dans le tableau." (p.44) ; toujours penser à l'interaction de l'oeuvre avec le spectateur

"L'escargot de Cossa n'est pas un trompe-l'oeil puisqu'il est peint sur le tableau et ne surgit pas de son espace. [...] Autrement dit, comme le vase de Lippi, comme l'escargot de Cossa, la sauterelle de Lotto fixe le lieu de l'entrée de notre regard dans le tableau. Elle ne nous dit pas ce qu'il faut regarder, mais comment regarder ce que nous voyons." (p.47-8)

"elle [la sauterelle de Lotto] est sortie de l'image pour mieux nous y faire entrer. C'est ce que Mauro Lucco a appelé la "perméabilité" qu'elle suggère entre le monde du tableau et le nôtre." (p.50) ; pourrait je appeler l'emploi de vrais fleurs ainsi?

-x-

l'oeil noir

"Bruegel prenait manifestement et résolument le contre-pied de cette tradition" (p.60) ; l'art c'est toujours soit basé sur le consensus soit sur la dispute

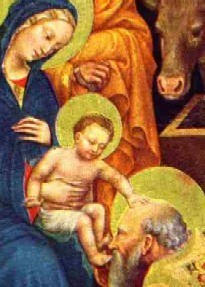

"Mais il a fallu attendre 1460 pour trouver le premier roi noir. Il est surpris d'apprendre la raison de cette nouveauté. Le Noir ayant traditionnellement une valeur négative, diabolique, dans la peinture chrétienne, il y tenait le rôle de l'esclave ou du bourreau. Son accession au rang prestigieux de roi mage a de quoi surprendre, sinon même choquer. [...] On le savait depuis longtemps et, pour les théologiens, la noirceur du troisième roi ne faisait aucun doute - alors même qu'on ne la rencontre jamais en peinture." (p.71-2) ; faut toujours regarder le centre du tableau car c'est cela le point le plus important d'une composition [le plus souvent, attention!]

"chez Gaspard, le luxe de l'habit royal devient ostentatoire, cet éclat étant sans doute à la fois autorisé et renforcé par le caractère exotique de la figure, permettant les fantaisies de formes, de matières et de couleurs les plus inventives [...] Ensuite, Gaspard est le plus jeune. Depuis un certain temps déjà, les Mages correspondaient aux 'trois âges de la vie'" (p.74)

"La circoncision prend dans ce contexte une importance considérable : c'est la première fois que le Dieu incarné verse, pour l'humanité, son 'très précieux sang' et c'est par elle, comme le déclare un prédicateur devant le pape Sixte IV, qu''il se révéla authentiquement incarné'." (p.79)

"Beau paradoxe : la peinture est là pour montrer que la foi n'a pas besoin de preuves, visuelles ou tangibles." (p.83)

"la figure du roi noir est désormais, depuis longtemps, trop courante pour signifier un lieu géographique particulier. Devenue banale, elle n'a plus de signification particulière ; elle se contente d'évoquer, à moindres frais, l'universalité de la révélation chrétienne." (p.89)

-x-

la toison de Madeleine

"pour peindre, il faut un pinceau et, un pinceau, c'est du poil. [...] Donc, on a toujours peint à poils. Et ne dites pas que je joue sur les mots : pinceau, qu'est ce que ça veut dire? Hein? D'où ça vient, pinceau? Ça vient du latin et ça veut dire petit pénis. Oui, monsieur, petit pénis, penicillus en latin, c'est Cicéron qui le dit, pinceau, petite queue, petit pénis." (p.119)

"C'est ce que les psys appellent la prise en considération de la figurabilité : quand vous ne pouvez pas vous représenter quelque chose, quand c'est interdit, vous substitutez autre chose qui y ressemble," (p.120)

-x-

la femme dans le coffre

"Si l'art a eu une histoire et s'il continue à en avoir une, c'est bien grâce au travail des artistes et, entre autres, à leur regard sur les oeuvres du passé, à la façon dont ils se les sont appropriées." (p.136) ; intéressant à comparer avec Kandinsky qui dit que chaque oeuvre est le fils de son temps...

"[Panofsky] dit qu'une description 'purement formelle' devrait ne voir que des éléments de composition 'totalement dénués de sens' ou possédant même une 'pluralité de sens' sur le plan spatial. [...] cette identification immédiate, préalable à toute analyse, d'éléments formels à des objets précis, qu'on se dépêche de nommer, empêche de comprendre le travail du peintre et, finalement, fait passer à côté du tableau." (p.140-1) ; comme le professeur a dit, il faut savoir la méthode de Panofsky mais ne pas l'employer dans sa totalité

"on ne devrait pas dire que la [Vénus d'Urbin] est dans un palais parce que l'unité du tableau n'est pas une unité spatiale. Il y a deux lieux, juxtaposés et tenus ensemble par la seule surface du tableau. [le tableau est incohérent]" (p.146-7) ; l'implication que c'est la surface, le support que fait la liaison de la composition est un thème très récurrent dans l'art contemporain...

"pointe de fuite - qui correspond à la position de notre regard face au tableau - et le pointe de distance - qui indique la distance à laquelle nous sommes, en théorie, situés par rapport au tableau et détermine la rapidité de la diminution apparente des grandeurs dans la profondeur." (p.148)

"Comme disent les Anglais, elle est moins nude que naked, moins nue que dénudée. Elle le sait mais n'en éprouve aucune mauvaise conscience. Elle ne connaît pas ce sentiment de honte qui fait toute la différence entre la nudité d'avant et celle d'après le Péché originel" (p.157) ; cela montre l'importance du vocabulaire employé

"dans les années 1860, Manet travaille sur la 'convention primordiale' de la peinture : un tableau est fait pour être regardé." (p.162)

"construire une surface qui regarde le spectateur. Manet a annulé toute perspective. Le tableau n'a aucune profondeur. Il est toute surface, et ce parti est confirmé par une minuscule transformation." (p.166)

"Narcisse est l'inventeur de la peinture parce qu'il suscite une image qu'il désire et qu'il ne peut ni ne doit toucher. Il est sans cesse pris entre le désir de l'embrasser, cette image, et la nécessité de se tenir à distance pour pouvoir la voir. C'est ça, l'érotique de la peinture qu'invente Alberti, [...] C'est exactement ce déplacement, ce retrait du toucher pour le voir que la Vénus d'Urbin nous impose par sa mise en scène. La servante agenouillée touche mais n'y voit rien, nous voyons mais nous ne pouvons pas toucher et, pourtant, la figure nous voit et se touche." (p.172-3) ; c'est la définition d'une image scoptique (?)

-x-

l'oeil du maître

"plutôt que de prétendre en vain fuir l'anachronisme comme la peste, tu es convaincu qu'il vaut mieux, quand c'est possible, le contrôle pour le faire fructifier." (p.180) ; il faut considérer qu'on porte toujours un jugement de notre époque lors des analyses