What do you think?

Rate this book

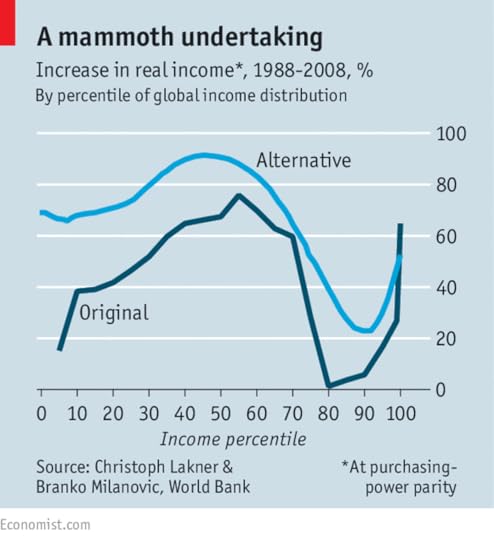

Ce livre de Branko Milanovic est devenu un classique à l'échelle mondiale, cité dans tous les débats sur les inégalités, notamment pour son graphique en forme d'éléphant, très largement commenté ces dernières années. Enfin disponible pour le public francophone, il permet de prendre la mesure des inégalités globales, et de connaître les périls qui menacent nos démocraties.

Ce livre dresse un panorama unique des inégalités économiques au sein des pays, et au plan mondial. Avec un talent pédagogique certain, il met en évidence les forces " bénéfiques " (accès à l'éducation, transferts sociaux, progressivité de l'impôt, etc.) ou " néfastes " (guerres, catastrophes naturelles, épidémies, etc.) qui influent sur les inégalités. Il identifie les grands gagnants de la mondialisation (les 1 % les plus riches des pays riches, les classes moyennes des pays émergents) et ses perdants (les classes populaires et moyennes des pays avancés).

Ce travail, fruit d'une analyse empirique sur une longue période et à grande échelle, permet notamment de comprendre les évolutions majeures de nos sociétés, comme les dérives ploutocratique aux États-Unis et populiste en Europe. En effet, Branko Milanovic est plus qu'un très bon économiste : tirant profit d'une culture historique et politique impressionnante, il montre l'imbrication des facteurs économiques et politiques (par exemple, pour expliquer les guerres ou les révolutions). Car tout n'est pas joué. Aux réactions défensives contre une mondialisation impérieuse, l'économiste préfère l'offensive, n'hésitant pas à réhabiliter l'État dans son rôle distributif, et à prôner une politique migratoire originale, ouverte et réaliste.

Devenu un classique dans de nombreux pays, cité dans maints débats, notamment pour son célèbre graphique en forme d'éléphant, cet ouvrage est enfin disponible pour le public francophone. Une lecture édifiante.

405 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 2007

Milanović argues that the cycle is broken now - or rather that there's a new model, where development (income growth) now means steady inequality rising in the post-industrial era (4).

Milanović argues that the cycle is broken now - or rather that there's a new model, where development (income growth) now means steady inequality rising in the post-industrial era (4).[S]ocial separatism [or c]lass bifurcation has many implications: politically, the middle class becomes increasingly irrelevant; production shifts toward luxuries, and social expenditures change from being directed toward education and infrastructure to policing. (198-9)Moreover, accidents of birth are starting to eclipse the American Dream's potential for economic mobility (216).

While the political system remains democratic in form because the freedom of speech and the right of association have been preserved and elections are free, the system is increasingly coming to resemble a plutocracy. (199)

mak[ing] access to the best schools more or less equal regardless of parental income and, more importantly, to equalize the quality of education across schools. (222)

The great winners have been the Asian poor and middle classes; the great losers the lower middle class of the rich world" (p20) (...)

They [globally very rich] too are the winners of globalization, we call them the "global plutocrats". (p22) (...)

44 percent of the absolute gain has gone into the hands of the richest 5 percent of people globally, with almost one-fifth on the total increment received by the top 1 percent (p24)

Will inequality Disappear as Globalization Continues?

No. The gains from globalization will not be evenly distributed.

"in 1820 only 20 percent of global inequality was due to differnce among countries. Most of global inquality (80 percent) resulted from differences within countries; that is, the fact that there were rich and poor people in England, China, Russia, and so on. It was class that mattered. (...)

By the mid-twentieth century, 80 percent of global inequality depended on where one was born (or lived, in the case of migration), and only 20 percent on one's social class. (p128)

decision (based on economic criteria alone) about where to migrate will also be influenced by the expectation regarding where he may end up in the recipient country's income distribution, and thus about how unequal the recipient's country's distribution is. Suppose that Sweden and the US have the same mean income. If a potential migrant expects to end up in the bottom part of the country's distribution, then he should migrate to Sweden rather that the US: poor people in Sweden are better of compared to the mean than they are in the US, and the citizenship premium, evaluated in the lower parts of the distribution, is greater. The opposite conclusion follow if he expects to end up in the upper part of the recipient country's distribution: he should then migrate to the US.

This last result has unpleasant implications for rich countries that are more egalitarian: they will tend to attract lower-skilled migrants who generally expect to end up in the bottom parts of the recipient countries' income distributions. (p135)

"capitalism has moved from being a system with complete separation between capital and labor incomes to a variant where the correlation between the two was negative (those who had labor incomes had very little capital income) to the "new capitalism," where this correlation is positive" (p186).

Larry Bartels finds that US senators are five to six times more likely to respond to the interests of the rich than to the interests of the middle class. Moreover, Bartels concludes, "there is no discernible evidence that the views of low-income constituents have any effect on their senators' voting"behavior." (p194)

Globalization makes increased taxation of the most significant contributor of inequality -namely, capital income- very difficult (p217)

International Migration Outlook 2013 (OECD), the most comprehensive study of the costs and benefits of migration in Europe, finds that, on average, an immigrant household contributed €2,000 more in taxes than it received in benefits" (footnote 41, p206)