What do you think?

Rate this book

319 pages, Hardcover

First published November 19, 2019

struggling with a particularly thorny chapter of John Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Like many men in England who fancied themselves of a certain class and intellectual capacity, he owned a copy; like most of those copies, the majority of the signatures in his had never been split by a blade. Sitting on his shelves, the volume had come to seem to him over the years like a fraudulent prop. It squatted there in accusation; it called him a pretender.This novel teaches us that we are all pretenders, in a way, when we claim to have access to the univocal truth. But it also affirms Howard's instincts: it is via honest intellectual struggle that we get just a little bit closer to the truth—which is much more easily done in the realms of science and medicine (as difficult as that may be in the particular case of trying to figure out how a woman could possibly give birth to rabbits) than it is in our personal lives.

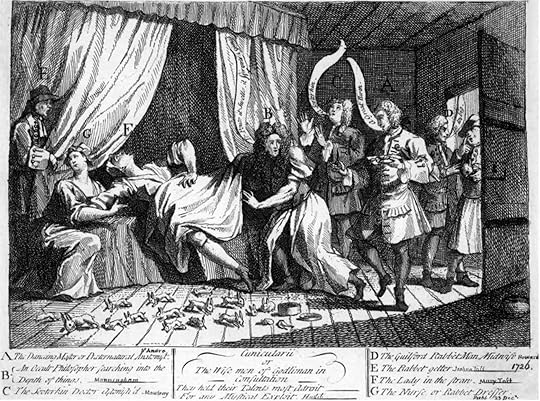

“I will grant you this one concession,” said Lord P——. “Any reasonable man would admit that we have no way of perceiving truth other than our eyes and ears and memories and instincts. And so the truth must, in the end, be a matter of consensus. By the time you arrived, the three surgeons had already formed that consensus, which even your title did not equip you to dispute. Just as the surgeon who took on the case before you would have found himself arrayed against two more of his profession."Truth, however provisional, politically-motivated, approximate, and consensual, still awaits these men, "at the end of inquiry" (as another, earlier pragmatist once said)—whenever that is. Sure, the Enlightenment dispelled much darkness. But that was just the start. Much darkness and perversion remained on the streets of London, and remains. And the Enlightenment is born of a piece with finance capitalism and racism—the Bank of England, founded just 30 years earlier, witnessed a spectacular crash after the South Sea Bubble burst in 1720, but that doesn't make much of an impact on the well-to-do in this novel, who rapaciously seek out ever more degrading entertainments, and who regale each other in a Coffee-House called The Blackamoor cos, don't you know, there are so few people of colour in London that they are more than exotic—they're very good for business.

[…]

“Recall your Locke,” Manningham said. “If a statement be not self-evident, there must be proof. We have, all four of us, delivered rabbits, or rabbit parts, from Toft with our own hands. But the evidence of our experience is limited—the inner workings of her body are a mystery to us, as is testified to by the competing hypotheses about Toft’s condition. Is this the work of God, or is it caused by some other physical abnormality, or are both of these the case? We cannot say conclusively.”

Thus the grass my horse has bit; the turfs my servant has cut; and the ore I have digged in any place, where I have a right to them in common with others, become my property, without the assignation or consent of any body. The labour that was mine, removing them out of that common state they were in, hath fixed my property in them.This humble servant begs Mr. Locke's "property" to do what it will with me, but to leave the horse alone, and maybe persuade its Master to put down his Locke, and take up Moll Flanders. Or Mary Toft, Rabbit Queen

In 1726, in the town of Godalming, England, a woman confounded the nation's medical community by giving birth to seventeen rabbits. This astonishing true story is the basis for Dexter Palmer's stunning, powerfully evocative new novel.I couldn't possibly reject an invitation like that...

There is no rarer and more precious comfort than this: when a man who is the sole possessor of a truth, and who feels himself misunderstood by all the world, looks into another man's eyes and finds, at last, that another believes what he believes, and he is no longer alone.The word Baroque might even apply.

—p.96