What do you think?

Rate this book

65 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2006

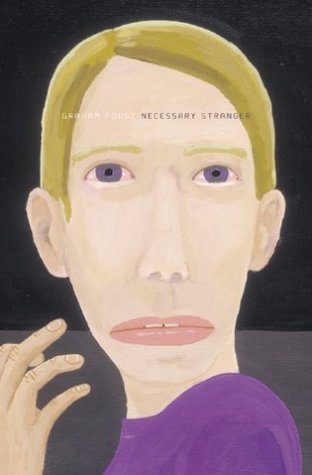

It's worth trying to catch out mid-tempo Foust, however, because it's possible to admire his skill while holding out some reservation about the project, and I suspect that my preference for Necessary Stranger, the third of Foust's (now) four books is a minority report. The folks who like this sort of thing seem to prefer it where else it's not so lived-in as here. The implicit claim, in the opening quote above, that the speaker is in pain, I suspect appeals to many more than it appeals to me. I take it as it is, and only wonder how such statements get into poems, and why. Foust, too, sets himself up as a critic of the sincerity he presumes is only that of "a person". However, the love poems in this volume speak to the midwestern pastoral that is Foust's most frequent mode, a jargon of authenticity taken for granted when the twenty-somethings of the Vietnam War era, from Larry Levis' The Wrecking Crew to Saint Geraud's Auto-necrophilia to Frank Stanford's The Singing Knives all worked out the cliches of that mode which was thrown into crisis by the Iowa revolt of Grenier, Watten and co. (Perhaps I will not be forgiven for the space/time metonymy of thinking it all happened at Iowa, but if we're to keep the subject poetry and music, which is Foust's gambit, not mine, then the pastoral is always-already and you're crazy if you don't think "Iowa City," as Foust names one poem here, figures significantly.)

The lessening in Foust's preferred litotes trope chastens the cliche while paying homage to the mode: "Late and unancient, inexact | as hands, I would move | as if by choice into my life," Foust tells us in "Number One Hit Song," and if I'm not too innured by the title's pastoral quip, then the volume pays off on the claim of having found a language that "moves as if by choice into" the poet's "life." The burden of the poet's belatedness, not just in relation to the midwestern surrealists invoked above, but also in relation to that realm of folk culture, including music, that was their Sixties context (where the thought of having a "Number One Hit Song" launched a thousand poetic ships) emerges in Foust's insistence on the representational crispness of seeing-into which goes into seeing. For Foust a poem is just a little slip of language that ties the psychic "real" to the world's objects in a way that resists the linguistic surfeit of pop opacity which makes him, to return to mid-tempo, "uncertain." The faith in that relationship between language's representational capacity and the psychic "real" is the premise it's easy to resist when it's insisted on in a certain "jargon" -- to resort, again, to Adorno's trope. I would defend this particular Foust title as his most distinguished because it feels most canny in its acknowledgement of such resistance.