What do you think?

Rate this book

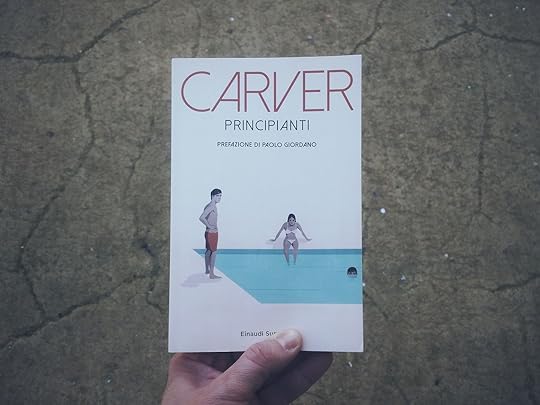

296 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2009

«A man without hands came to the door to sell me a photograph of my house»

Yes, the protagonist of "Viewfinder", one of the shortest novel of this collection, has two hooks for hands. And the first edition of this collection of novels suffered the same fate of those amputations: dramatically reduced by Carver's editor, Gordon Lish. Probably Lish's intention was to ride the wave of minimalism that was popular those days. But this is frowned upon by Carver:

«I don't like it. There is something in that "minimalist" looking like a miserable picture, or a hasty execution. And I don't like it»Impossible to think, hasty execution is the complete opposite of the meticulous Carver's writing, who struggles in his novels for the best choice of words. However, to be honest, Lish makes also good choices in his revisions, as emphasized by Carver in some letters to the editor. But in the same letters there is also some desperation, the despair of an author assisting to the mutilation of his work, the distortion of what he perceives as the primary sense of his novels.

These deep reduction generate What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, first edition of this collection. But what we talk about when we talk about love, then? Carver admits we're all "beginners" in love. But one thing is for sure: Carverian love is a very thin one, be it the love between two partners or the one of the parents for their children.

Last entry: in these novels there's never a well-defined ending. Carver focuses on the description of a situation leading towards the epilogue, but the ending is choosen by the readership. And each time, the ending that Carver let me imagine brings me a sense of unease, a little hopelessness that makes me know how Raymond Carver has a way with the words.

Vote: 8

«Un uomo senza mani si è presentato alla porta per vendermi una foto di casa mia»

Si, perchè il protagonista di Mirino, uno dei racconti più brevi di questa raccolta, possiede degli uncini al posto delle mani. Lo stesso destino di questi arti amputati lo hanno subito nella loro prima edizione tutti i racconti di questa raccolta: tagliati in larga parte per opera del suo editor, Gordon Lish. Probabilmente le intenzioni di Lish erano quelle di cavalcare l'onda del minimalismo in voga all'epoca. Etichetta di minimalista che però non è vista di buon occhio da Carver:

«Non mi piace. C'è qualcosa in quel minimalista che dà l'idea di una visione misera e di un'esecuzione frettolosa. E non mi piace»Figuriamoci, esecuzione frettolosa è proprio l'opposto del modo di scrivere meticoloso di Carver, che fa della scelta del vocabolo giusto una questione essenziale. Tuttavia, ad essere sincero, Lish è anche efficace in alcune sue scelte, come sottolinea Carver stesso in alcune sue lettere all'editore. Dalle stesse lettere trapela però anche una certa disperazione, lo sconforto di un autore che vede mutilate le sue opere con uno stravolgimento di quello che lui percepisce come il senso primario di quello che ha scritto.

Da questi profondi tagli nasce Di cosa parliamo quando parliamo d'amore, prima edizione di questa raccolta. Ma di cosa parliamo quando parliamo d'amore? Carver ammette che siamo tutti principianti, in amore. Una cosa è certa: l'amore carveriano è estremamente labile. Sia esso l'amore di due compagni o quello dei genitori per i figli.

Ultima nota: non c'è mai un finale definito, in questi racconti. Carver si concentra sulla vicenda, sulla descrizione di una situazione che conduce verso un epilogo. Però il finale se lo scelgono i lettori. E ogni volta, il finale che Carver mi lascia immaginare mi procura un senso di disagio, una piccola disperazione che mi fa capire che Raymond Carver con le parole ci sa fare maledettamente bene.

Voto: 8