This book could be easily put to the stage (OK, a liberal stage), as Greenwell paints every scene before diving into the inevitable return of Mitko (in person, or in thought). This book does not feel like fiction - the story sounds far too real. The subtleties of the Bulgarian language (formal vs informal) grace most pages and add greatly to the understanding of the tone of each conversation. It is these very small things that I loved so much about reading this book.

The book's opening chapter is strong enough that I'm not sure how I found this book on the shelves of my public library. (This might be tough 'on stage'). But these scenes do not dominate the narrative. The unnamed teacher has stories of his childhood in the book that tell us of his earliest desire for boys his age, and the serious parental, step-parental, and parents-of-parents problems that formed him. He is openly gay to his school and students in a country where this is done in secret. His openness to himself lets his desires always crumble, with the best intentions, when Mitko comes to buzz the door and and then work his charm. There truly was no remedy.

It is the simple plot of this book that works its magic in me, personally. The ending is perfectly matched to this story.

I started reading the book, and looked up a few quotes on Goodreads. They sounded good, but did not leap out at me. Once I now KNOW where these quotes occur in the book, I get so much more emotional when I read them. My favorites:

“Sometimes we talked the whole night long, as one does only in adolescence or very early in love. I was happy, but also I felt an anxiety that gnawed at me and for which I could find no cause, that gnawed at me more deeply precisely because I could find no cause.”

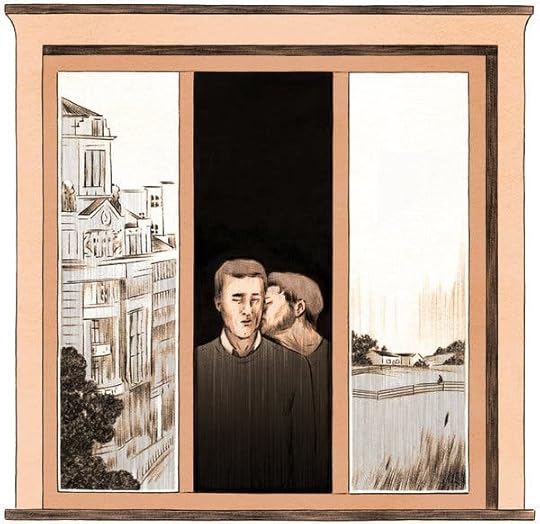

“K. hung his arm around my neck. It was a casual gesture but one I wasn’t used to, and I was almost frightened by the happiness that overtook me, that filled me up and charged me and at the same time carried a thread; it was too unrestrained, there was nothing to keep it in check. I felt solid again as I walked with him, more certain of myself than I had been for years, with his arm around my neck and my own slung at his waist We knocked against each other but what did it matter, there was no one to see us, we moved with an awkward freedom but a freedom nonetheless.”

"Maybe they were a mistake, my years in this country, maybe the illness I had caught was just a confirmation of it. What had I done but extend my rootlessness, the series of fall starts that became more difficult to defend as I got older? I think I hoped I would feel new in a new country, but I wasn’t new here, and if there was comfort in the idea that my have the troll I niece had a cause, that if I was ill-fitted to the place there was good reason, it was a false comfort, a way of running away from real remedy. But then I didn’t truly believe there was a remedy, I thought as I stepped down from the platform into the snow, walking into the boulevard, and how I could regret the choices that had brought me, by whatever path, to R., any more than I could regret those that had led to Mitko and to moments that flared in my memory, that I knew I would cherish whatever their consequences."

“Making poems was a way of loving things, I had always thought, of preserving them, of living moments twice; or more than that, it was a way of living more fully, of bestowing on experience a richer meaning."

“He had always been alone, I thought, gazing at a world in which he had never found a place and that was now almost perfectly indifferent to him; he was incapable even of disturbing it, of making a sound it could be bothered to hear.”

“Love isn’t just a matter of looking at someone, I think now, but also of looking with them, of facing what they face.”