What do you think?

Rate this book

400 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1972

Society in America was always trying, almost as blindly as an earthworm, to realize and understand itself; to catch up with its own head, and to twist about in search of its tail. Society offered the profile of a long, straggling caravan, stretching loosely toward the prairies, its few score of leaders far in advance and its millions of immigrants, negroes and Indians far in the rear, somewhere in archaic time…One could divine pretty nearly where the force lay, since the last ten years [the 1860s:] had given to the great mechanical energies—coal, iron, steam—a distinct superiority in power over the old industrial elements—agriculture, handiwork, and learning...(Henry Adams)

Jay Gould is the mightiest disaster which has ever befallen this country. People had desired money before his day, but he taught them to fall down and worship it. They had respected men of means before his day, but along with this respect was joined the respect due to the character and industry which had accumulated it. But Jay Gould taught the entire nation to make a god of the money and the man, no matter how the money may have been accumulated.(Mark Twain)

The whites who administered Native American subjugation claimed to be recruiting the Indians to join them in a truer, more coherent worldview—but whether it was about spirituality and the afterlife, the role of women, the nature of glaciers, the age of the world, or the theory of evolution, these white Victorians were in a world topsy-turvy with change, uncertainty and controversy. Deference was paid to Christianity and honest agricultural toil, but more than few questioned the former, and most, as the gold rushes, confidence men, and lionized millionaires proved, would gladly escape the latter. So the attempt to make Indians into Christian agriculturists was akin to those contemporary efforts whereby charities send cast-off clothing to impoverished regions: the Indians were being handed a system that was worn out...(Rebecca Solnit)

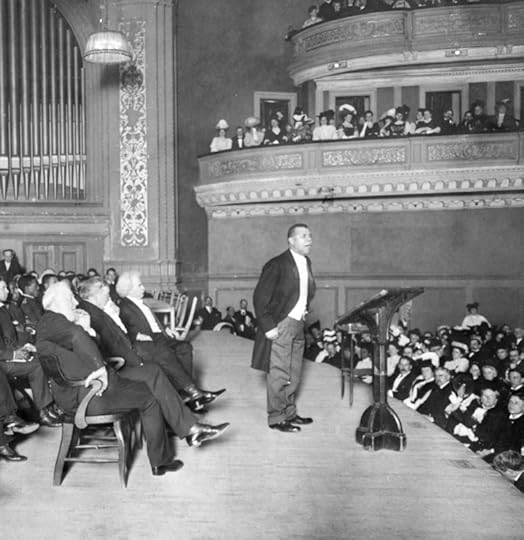

...blacks had virtually nothing to do with making Washington a black leader. The death of Frederick Douglass only a few months before the Atlanta Address not only left a vacuum for someone to fill, but marked the end of an era in which the old fighter for human rights had personified the aspirations of the race. But it was white people who chose Washington to give the address, and white people’s acclaim that established him as the negro of the hour. Southern conservatives in charge of the Atlanta Exposition choose Booker Washington rather than any one of a dozen Negroes at least as prominent, because they regarded him as a “safe” Negro counselor, one whom they wanted to encourage, and his speeches in Atlanta in 1893 and before the Congressional committee in 1894 were reassurances of his conservatism. The Southerners sought a black man who would symbolize that Reconstruction was over, and one they could consider an ally against not only the old Yankee enemy but the Southern Populist and labor organizer. They wanted a black spokesman who could reassure them against the renewal of black competition and racial strife. And Northern whites as well were in search of a black leader who could give them a rest from the eternal race problem. They, too, were ready to declare an end to the Civil War and Reconstruction, and sought an intersectional truce. They were ready for an alliance of Northern and Southern capital and for political alliances across sectional lines. Booker T. Washington’s racial Compromise of 1895, as August Meier notes, “expressed Negro accommodation to the social conditions implicit in the earlier Compromise of 1877.” As often in his career, Washington’s rise coincided with a setback of his race.