What do you think?

Rate this book

290 pages, Paperback

First published August 1, 1997

"With the fiftieth anniversary of the war’s end approaching, I found myself feeling outraged and betrayed when not only our national museum, the Smithsonian Institution, but some American historians as well attempted to change the history of the war in the Pacific. Suddenly I was hearing that Americans had been the aggressors and the Japanese had been the victims. The exhibit of the Enola Gay originally proposed by the Smithsonian—an exhibit that would be viewed by millions of Americans who would undoubtedly accept it as a factual representation of the war— was for me the final insult to the truth. To quote from the script of that planned exhibit: “For most Americans, this war . . . was a war of vengeance. For most Japanese, it was a war to defend their unique culture against Western imperialism.”

I had occasion to read not only the original script of that planned exhibit but several of the rewrites that followed. They grossly minimized casualty estimates for an invasion of the Japanese mainland, one of the factors that had driven President Truman’s decision to drop the bombs. They placed greater emphasis on alleged Allied racism against the Asians than, for example, on the hundreds of navy men who had been entombed in the USS Arizona at the bottom of Pearl Harbor. Some of those men were trapped for days before they died. Forty-nine photographs were to be exhibited showing the suffering Japanese victims of the war, and only three photographs of wounded Americans. This selection of exhibits was puzzling, given that the history of the war in the Pacific was also synonymous with Corregidor,

Bataan, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and Saipan. It was a history of Japanese prisoner of war camps—sites of unspeakable inhumanities—of kamikazes, and of the infamous medical experiments conducted by Japanese doctors on live prisoners of war. Were Americans, one might ask upon learning all the

facts, compelled to be brutalized until the Japanese were ready to say, We’ll stop?"

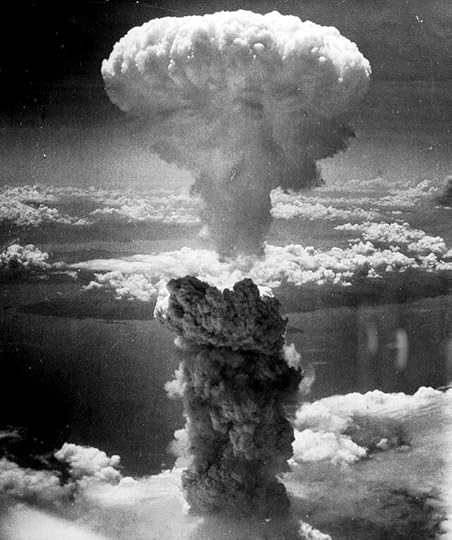

"LeMay had a solution, which Paul Tibbets had recommended several months earlier. Instead of high-altitude bombing, he would send hundreds of B-29s in at 8,000 feet at night. Each airplane would carry thousands of pounds of incendiary bombs filled with napalm, which would incinerate entire Japanese cities and the war industries located in them. The tactic would take advantage of the mostly wooden structures built in Japan and the fact that the Japanese had concentrated their major war industries in the hearts of most of their large cities.

LeMay’s goal was not to bomb civilians. He wanted to destroy Japan’s industrial capacity. The night before a mission his pilots would drop leaflets over target cities warning civilians that the bombing was imminent and they should evacuate. If his plans were to bomb two cities, leaflets would be dropped over four. The Japanese military, however, with the assent of the political leaders, explicitly kept the civilians in harm’s way. When Kyoto first appeared on a list of bomber targets, LeMay expressed opposition. He preferred Hiroshima because of its concentration of troops and factories."

"The firebombings were horrific. City after city was incinerated. The fires, started by the napalm and fueled by the burning wooden structures, consumed all the available oxygen in the area. The lack of oxygen would cause a vacuum that generated high-velocity winds that would implode, further intensifying and spreading the ever-consuming fires.

Temperatures exceeded 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit. The napalm itself was an insidious weapon because it could not be extinguished. It splattered and stuck to any surface it struck: a building, a house, a person.

In mid-March the campaign reached its apex. On the night of March 9, 334 B-29s struck Tokyo, blanketing the city with firebombs. Tokyo was reduced to rubble. It was the single most destructive bombing in history— 125,000 wounded, 97,000 dead, over a million left homeless. In a ten-day period in March, thirty-two square miles of Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe were leveled.

The Japanese fought on..."

"...In April it became clear that a final assault on the mainland of Japan would be necessary. The Japanese showed no inclination to surrender. In fact, as American forces drew closer to the mainland, the Japanese military became even more fanatical and suicidal. As brutal as the battle for Iwo Jima had been—leaving 21,000 Americans wounded and over 6,000 marines, soldiers, and sailors dead for an eight-square-mile hunk of rock— Okinawa revealed an even more vivid and chilling window on things to come. Just 325 miles off the coast of Japan’s southern island of Kyushu, Okinawa was the site of the last and largest amphibious invasion of the war.

Defending it, the Japanese fought for almost three months in a hopeless struggle. Virtually all of the Japanese troops fought to the death—110,000 of them. Taking the island required half a million men. Almost 50,000 of them—marines, airmen, sailors, and soldiers—were wounded or killed.

The Japanese had also introduced another terror to the hell that had become the Pacific: the kamikaze, “the Divine Wind.” Young flyers willingly committed suicide by diving their bombladen aircraft into our fleet so that they could kill as many Americans as possible in one single effort. By their glorious sacrifice, they were promised eternal life. Their orders were more religious than military: ‘The death of a single one of you will be the birth of a million others. . . . Choose a death which brings about a maximum result.”

For centuries Japan had been a closed militaristic society. In five hundred years it had never lost a battle. The code of the samurai guided its destiny. During World War II not a single Japanese military unit surrendered. Bushido, “the way of the warrior,” was not only ingrained in the psyche of every Japanese fighter, it was also codified in the Japanese Field Service Regulations, which made being taken alive a court-martial offense. This was the culture and the mind-set we faced..."