For thirty-nine years, from 1960 to 1999, female community thrived at the [Radcliffe] Institute. The complete merger of Harvard and Radcliffe in 1999 created one major change over the 1970s partial merger: out of the ashes of The Radcliffe Institute was borne the Harvard-Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study open to all genders. In a moment this rich community supportive of mature women and their creativity and scholarship was gone.

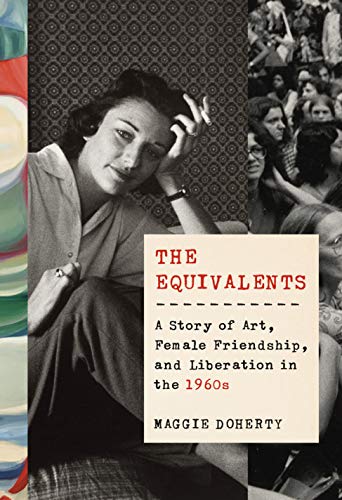

In 1960, Polly Bunting, the new president of Radcliffe College, founded The Radcliffe Institute on an idea: when provided with institutional support and intellectual community, [women] artists, writers, and scholars will produce better work than they would on their own. This was not an undergraduate program, but one designed for women who had at least a college degree, maybe even advanced degrees and some creative success, but due to the Cold War emphasis on women being wives and mothers to the exclusion of all else, their creativity was stifled, even abandonned. Doherty here gives us not only a history of the Institute itself, but the truth of that idea through the bios of 5 of its first fellows known as 'The Equivalents'. There were of course flaws to the program generally reflecting both the prejudices and expectations of the times and those in charge -- it was initially expected only mature married white privileged women in the Boston area would be considered -- but it evolved as seen by many who soon passed through the program such as Alice Walker. The institute fellows received financial support in the form of grants, a private office, access to libraries and classrooms of Harvard and Radcliffe over a 2 year period.

The Equivalents were poets Anne Sexton and Maxine Kumin, writer Tillie Olsen, sculptress Marina Pineda, and artist Barbara Fink. They were friends and collaborators. Sexton and Kumin edited each others work, Fink provided cover art and illustrations for certain volumes of poetry, a Pineda Oracle statue sits still in the Radcliffe Yard at Harvard. All went on to great fame and success, awards and even Pulitzers, their 2 year fellowships at the Institute providing necessary dedicated time to pursue their art and studies. There stories are compelling.

Doherty thankfully provides us with in depth bios of each of these women, though Sexton, Kumin and Olsen dominate. Many others pass through who are not part of the institute but provided important roles: Sylvia Plath, Betty Friedan, Robert Lowell, Elizabeth Hardwick and Alice Walker to name but a few. It is through all these stories and the historical events in the background of these women's lives and the Institute that we see the genesis and evolution of the women's movement, beautifully rendered here, including the various divisions that rapidly occurred primarily based in class and race as well as privilege and what exactly feminism and liberation required for each group.

I was thoroughly engaged in reading this the entire time, readily picking it back up to read another chapter or two. It was also nostalgic to a degree. I was a child in the 60s but when I entered Barnard College as a freshman in fall 1973, I very much was one of the first generation of women who followed and benefited from the path forged by all these women, allowing me to take classes in 'women's studies', write a thesis on the political writings of a French female author, even pursue a profession on my terms that earlier only a tiny number of women entered, and even fewer with agrarian backgrounds.

It's good that I ended up reading this at this particular time when it feels as if so many advances fought for are being stripped away because it has made me remember that we still have come a long way and hold on to much. We just can't ease up and stop pushing, demanding, and fighting for a second.

This book was written during the Trump presidency and published in spring 2020. It's been under the radar, likely due to pandemic, though also probably because no one has heard of The Radcliffe Institute. I certainly did not know about it or the impact it had. If you are interested in writing, poetry, feminism, women's history, education and educational history, any of these women, the intellectual world of Boston and its suburbs in the 60s and 70s, and even mental illness and suicide among writers and poets, you must read this.