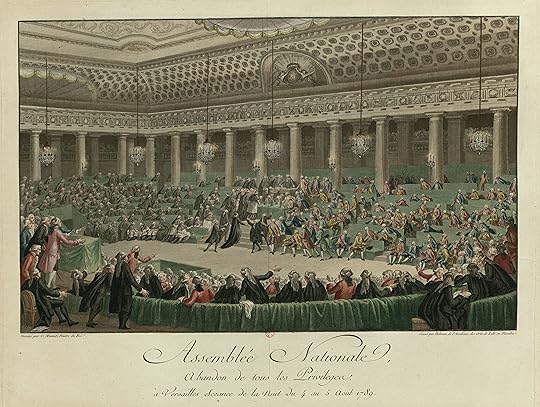

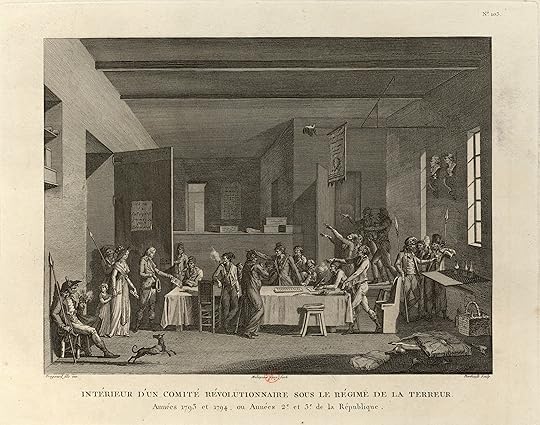

During the French Revolution, the government created a new calendar, which dated years from the beginning of its rule. It renamed the days and the months, and even instituted a new clock. This is because the partisans of the Revolution wished to create the impression of a radical rupture with the past. Through an close analysis of the Revolution's history, especially its intellectual foundations, Furet convincingly demonstrates that this impression of radical novelty was an illusion. According to Furet, pre-revolutionary France was essentially "a republic in the guise of an absolute monarchy," since power was in practice distributed among many agents. The makers of the Revolution retained, and even magnified, the idea of centralized, absolute power, but attempted to transfer this to "the people," conceived in the abstract. But the citizens are not a monolithic body, but, rather, a collection of groups and individuals. The only way in which they could hold, or appear to hold, such power was as embodied in a single person. For a while Robespierre became, in effect, the monarch of France, and soon after that position was taken over by Napoleon, who became far more powerful than the beheaded king had ever been. The major structural change was only that the monarchy was integrated into a predominantly bourgeois, rather than a primarily feudal, social order. The old formula was reversed, and France became "an absolute monarch in the guise of a republic." The changes in the calendar were only used for a very short time, but we still often date the "modern era" from the French Revolution. But if, as Furet maintains, there was no lack of continuity with the preceding period, modernity itself may be, as Bruno LaTour has argued, an illusion.