What do you think?

Rate this book

320 pages, Paperback

First published August 22, 2017

The family is raised, the work’s done. That can’t be it, can it? There’s ten or twenty years left over, as it were. We’ve cut the life of our cloth wrongly. It doesn’t fit …. I have a sense of drift. I want to do something with the time I have left. Other than watch you drink

He believed that everything and everybody in the world was worthy of notice, but the person beside him was something beyond that. To him her presence was as important as the world. And the stars around it. If she was an instance of the goodness in this world then passing through by her side was miracle enough

And did you get whatThis poem, "Late Fragment" by Raymond Carver, is just about the last thing he ever wrote. Bernard MacLaverty quotes it near the end of his beautiful novel, and it distills the essence of the entire book. But it comes at a moment of despair; any transcendence is hard won and must be taken partly on faith. The spiritual arc of the book and its necessary incompletion are both perfect. Having said that, I could end my review. But won't; there is much else to say.

you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

beloved on the earth.

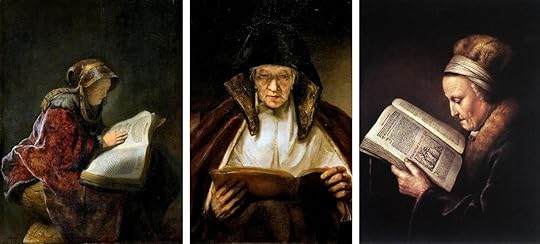

There was a crowd gathered around it. It was huge, big as a hoarding, a great slash of browns and yellows and reds. Two figures, a man and a woman on the edge of intimacy, or perhaps just after, about to coorie* in to one another. Hands. Hands everywhere. A painting about touch. Stella joined the crowd and wormed her way to the front. Gerry watched her bite her lip as she gazed. She became aware of Gerry watching her. He excused himself and threaded his way to her side.Stella sits down to rest while Gerry wanders off. On an opposite wall, she sees a large painting of a woman reading. Later, she tries to buy a postcard of it, but they are sold out. The assistant offers her a different version. "There are many old women reading," she says. And indeed there are: two by Rembrandt and one by Gerrit Dou at least. I find it interesting that MacLaverty should devote a full page to the picture of the beginning of a marriage, but treat as commonplace the subject of a woman nearing the end of one. Threescore years and then… what?

'Well?'

'There's a great tenderness in him,' she said. 'You can see that he cherishes her.'

She wanted to live the life of her Catholicism. This was where her kindness, if she had any, her generosity, her sense of justice had all come from. And her humility, she must not forget humility. Catholicism was her source of spiritual stem cells. They could turn into anything her spiritual being required.Stem cells, of course, belong to the embryo; they are all possibility, looking forward. Stella's crisis is as much a spiritual as a marital one. While nearly all of Gerry's monologues look backwards—anything beyond the immediate present being obliterated by his excessive drinking—she looks forward to a future she cannot see, asking questions that have no easy answers. What is her purpose in life? What is her debt to God, and how may she repay it in practical terms?

There was a brick archway which led to a dark passage. She hesitantly walked its dry length, hearing her own footsteps echoing. The passageway led out into a space which took her breath away. The notion of being born came to her. […] Grass, winter trees, a ring of neat ancient houses with their backs to the world, all looking inwards—like covered wagons pulled into a circle—creating their own shelter. An inner court or Roman atrium. In the centre of the green space stood a Christ-like statue facing a red-brick church. It was the same place she had seen on her computer screen at home. And the silence was the same. The passageway she had come through had edited out the noise of Amsterdam—the trains, the trams, the cars, all gone. As if to emphasise the quiet, some sparrows cheeped within the enclosure of houses.The place is not named at first, but I recognized it: the Begijnhof, the ancient community of Beguines, or secular nuns committed to a life of faith and service, though without taking final vows. Stella's several visits there, alone or with Gerry, are touching but also heartbreaking.

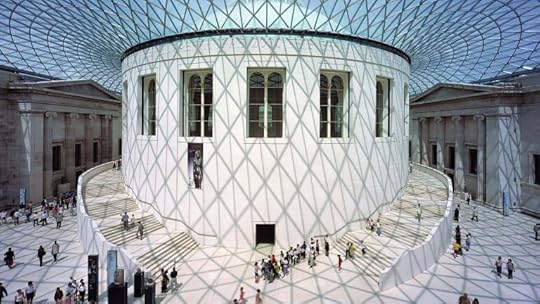

A thing that really took his breath away was Norman Foster's roof over the Great Court of the British Museum—the audacity and brilliance of it. The approach inside the building from a periphery of darkness into the thrilling light at its centre—the largest covered square in Europe—was utterly wonderful. If it was about anything, architecture was about shedding light.Looking for a photo, though, I was equally struck by the cylindrical structure in the middle, which relates to a building in Ireland that Gerry worked on, Burt Chapel in Donegal by the architect Liam McCormick. And to its inspiration, the circular Iron Age fort of Grianan Aileach, further up the hill, a marvelous rhyming of three round objects.

But Stella was more interested in the view. Give or take some trees and a road or two, she said, it was what you would have seen two thousand years ago. With one slow turn of the head you could see the counties of Donegal, Derry and Tyrone, with Lough Swilly and Lough Foyle in the middle of it all. It made her feel glad to be Celtic. Silence in such a place, at such a height, is hard to come by because the wind is always there bluffing your ears into thinking there is no noise. Maybe the bleat of a sheep and no sheep to be seen. She put her hand in the air to find the wind's direction. Stella. A star with her hair blowing. Eclipsing all else. Her hand in the air.======