What do you think?

Rate this book

138 pages, Paperback

First published October 22, 2015

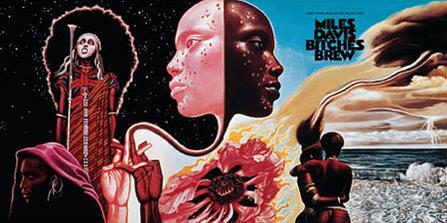

it will never be the same again now, after in a silent way and after BITCHES BREW. listen to this. how can it ever be the same? i don't mean you can't listen to ben. how silly. we can always listen to ben play funny valentine, until the end of the world it will be beautiful and how can anything be more beautiful than hodges playing passion flower? he never made a mistake in 40 years. it's not more beautiful, just different. a new beauty. a different beauty. the other beauty is still beauty. this is new and right now it has the edge of newness and that snapping fire you sense when you go out there from the spaceship where nobody has ever been before. - excerpted from Ralph J. Gleason’s liner notes* for the original double LP edition of Bitches Brew. These were intentionally written in lower case letters.