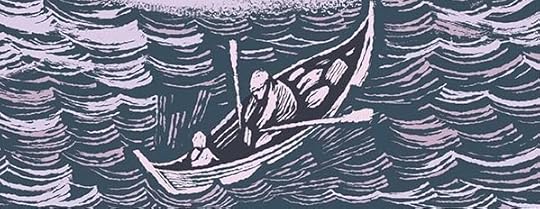

Winter begins with a storm. They call it the First Winter Storm. There have been earlier storms, in August and September, for example, bringing sudden and merciless changes to their lives.

The First Winter Storm, on the other hand, is quite a different matter.

It is violent every single time and makes its entrance with a vengeance, they have never experienced anything like it, even though it happened last year. This is the origin of the phrase "in living memory", they have simply forgotten how it was, since they have no choice but to ride the storm, the hell on earth, as best they can, and erase it from their memories as soon as possible.

[..]

The sight of her father is the worst. Had Ingrid not known better she would have thought he was afraid, and he never is. Islanders are never afraid, if they were they wouldn't be able to live here, they would have to pack their goods and chattels and move and be like everyone else in the forest and valleys, it would be a catastrophe, islanders have a dark disposition, they are beset not with fear but solemnity.

The Unseen by Roy Jacobsen is set in the first half of the 20th Century (although there is little to date the novel), on the fictional Barrøy island off the coast of Norway in the Helgelandskysten area.

It is a little under one kilometre from north to south, and half a kilometre from east to west, it has lots of crags and small grassy hollows and sells, deep coves cut into its coast and there are long rugged headlands and three white beaches. And even though on a normal day they can stand in the yard and keep an eye on the sheep, they are not so easy to spot when they are lying down in he long grass, the same goes for people, even an island has its secrets.

The fisherman-cum-farmer Hans Barrøy [is] the island's rightful owner and head of its sole family, comprising his strong-willed wife Maria, born on a neighbouring island, Hans's widowed father Martin, no longer head of the family which he represents, his much younger sister Barbro, a hard worker but rather backwards, and his young daughter Ingrid, three when the novel opens but already troubling her father with wisdom beyond her years, and who he anxiously watches for signs of the one-child-in-a-generation affliction from which he aunt suffers:

"Tha laughs at ev'rythin' nu," he says, reflecting that she knows the difference between play and earnest, she seldom cries, doesn't disobey or show defiance, is never ill, and she learns what she needs to, this disquiet he will have to drive from his mind.

Life on the island is elemental and hard. Hans has to leave his family for several months each year to join a fishing boat, in which he proudly has a full share of the proceeds, as well as (unbeknowest) to his family drawing on bank loans, in order to finance the costs of maintaining the island and, in particular, his own ambitious plans to extend their house and build a proper pier. Much of the building material still comes from flotsam, jetsam and driftwood: Whatever is washed up on an island belongs to the finder and the islanders find a lot. In those days there was no oil-wealth funded Nordic model providing support to the islanders:

As the terrain is so open and exposed someone might well up with the bright idea of clothing the coast in evergreen, spruce or pines for example, and establish idealistic nurseries around Norway and start to ship out large quantities of tiny spruce trees, donating them free of charge to the inhabitants of smaller and bigger islands alike, while telling them that if you plant these trees on your land and let them grow, succeeding generations will have fuel and timber too. The wind will stop blowing the soil into the sea, and both man and beast will enjoy shelter and peace where hitherto they had the wind in their hair day and night; but then the islands would no longer look like floating temples on the horizon, they would resemble neglected wastelands of sedge grass and northern dock. No, no one would think of doing this, of destroying a horizon. The horizon is probably the most important resource they have out here, the quivering optic nerve in a dream although they barely notice it, let alone attempt to articulate its significance. No, nobody would even consider doing this until the country attains such wealth that it is in the process of going to wrack and ruin.

Hans expects to live out his life on the island but Barbro wants to find a role in service on the mainland. Nobody can leave an island. An island is a cosmos in a nutshell, where the stars slumber in the grass beneath the snow. But occasionally someone tries. (in the original: Ingen kan forlade en ø, en ø er et kosmos i en nøddeskal med stjernerne sovende i græsset under sneen.")

Concerned at her being mistreated and abused - her first putative employer manages to refer to her as "the imbecile" three times as she shows them the room Hans's sister is to share with the other maid - Hans keeps insisting Barbro returns to the island until she takes matters, and the oars of the family boat, into her own hands, but even then she eventually finds her way back.

Hans Barrøy had three dreams: he dreamed about a boat with a motor, about a bigger island and a different life. He mentioned the first two dreams readily and often, and to all and sundry, the last he never talked about, not even to himself.

Maria had three dreams too: more children, a smaller island and - a different life. Unlike her husband she often thought about the last of these, and her yearning grew and grew as the first two paled and withered.

But it is Ingrid, still biologically a child, who, as the seasons turn and the cycle of life progresses, has to take on the island and their dreams.

The novel has been translated by the deservedly renowed Don Bartlett, translator of the excellent Karl Ove Knausgård, Per Petterson and Lars Saabye Christensen as well as the best-selling Jo Nesbø and Jostein Gaarder. Although this, as well as Jacobsen's previous novels and novels by Erlend Loe, has been co-translated by Don Shaw.

The translation generally lives up to Bartlett's very high standards, although the attempt to render the dialect of the locals into English fell a little flat for me, with lines such as

"My word, hvur bitty it is. A can scarce see th' houses"

and

"By Jove, A can see th' rectory too"

Norwegian literature is perhaps my favourite in Europe - with authors such as Dag Solstad and Jan Kjærstad, as well of course as Hamsun, to add to the aforementioned Karl Ove Knausgård, Per Petterson and Lars Saabye Christensen - and this novel adds another name to that impressive list.

I would hope to see this on the MBI shortlist.

It is always the person who has been away who gains the greatest pleasure from knowing time stands still.