“a state of permanent ebullience”

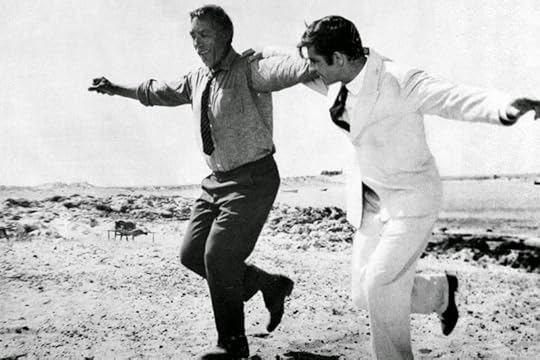

On a hot April afternoon in Lucknow, India, about 55 years ago, an American friend of mine handed me “The Greek Passion”, one of the great novels by Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis. I had never heard of him, nor had I yet read more than a half dozen novels by any great writer. I was still sunk in non-fiction or sci-fi and pop novels. I read the book and immediately, Kazantzakis became my favorite writer. I read “Zorba the Greek”, “Freedom or Death”, “Report to Greco”, another minor novel and a travel book. If you mentioned him in America, all you got was “who?” I ran out of steam, a certain fatigue set in, as it sometimes will. I abandoned my hero for forty years until I got around to reading this most-unusual biography which smacks of autobiography, but then---not really.

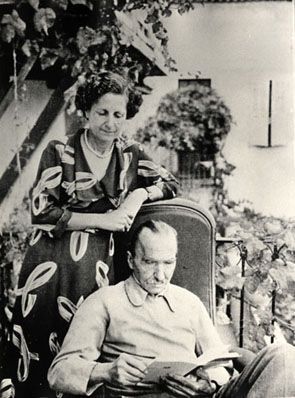

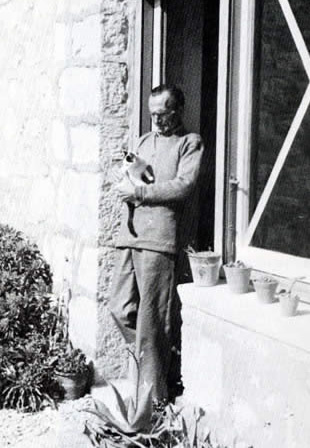

What am I talking about? Kazantzakis, born in 1883 to a Cretan family, no doubt wrote many letters to friends and lovers before he met Eleni Samios. He also filled many a notebook with his thoughts. The two became inseparable, but unfortunately due to illness (Eleni) and the travels of the always-impecunious Nikos, they were forced to communicate by letter in that age before email and iPhones. That’s why there were eventually a huge stock of letters from Nikos which you may read if you get hold of this book. They married after many years of togetherness and during WW II holed up on Aegina, a small island not far from Athens. Later, the duo were forced out of Greece because Kazantzakis had leftist sympathies, had once been a Communist and was looked upon favorably (for a time) in Moscow. The more they lived together in a European exile, the fewer letters they wrote, not unnaturally, so the latter part of the book contains more letters to friends or literary colleagues, plus memories added by Eleni (Helen) who compiled this whole book.

I am a New Englander, if Jewish, and grew up avoiding open displays of feeling, trying to be rational at all times, counting displays of temper and emotion as lapses. Not Kazantzakis. Reading his letters is like chewing your way through an ocean of rich chocolate fudge, or throwing bad spaghetti against the wall!

“The nearest sound becomes gigantic. Words with us are like bombshells, a hidden and frightening power, and we liberate it. The words “bread”, “God”, “fish”, “stone”, “sea” explode in our hearts. When it rains and snows and I walk bareheaded, alone on a mountain, or by the edge of the sea, I feel that the whole world is drowned and that the curse of God, like a cataclysm, has risen up to my neck. But on the surface of the water, my head floats, containing all the seeds of good and evil….” (p.87)

“I think of you all the time, every moment, divining all your sorrows, weaknesses, vacillations, violent desire—your whole individual adventure is growing inside me into a universal horror and futility. And at the same time, all the rhythm of the world is becoming incorporated, assuming a countenance, voice and sweetness in your own pale, determined face.” (p.119)

“And now throughout this journey another Siren—the sweetest and most faithful of them all, la Mort—has often overwhelmed me. If I could only die! If I could only die! There could be no greater happiness for me, I think. Because I love this earth too much, the air, woman, thought, the sea—and I cannot get my fill of them.” (p.148)

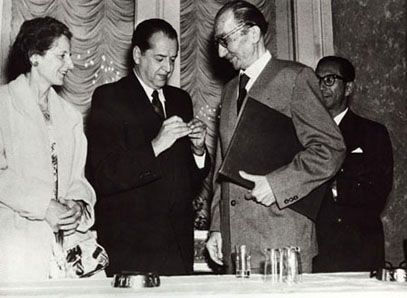

He scorns “poor little rational rationalities” (p.506). If you feel the same, you’re gonna love this book, these romantic letters full of emotion, fruit and wine. But while I still like his novels, I got rather tired of poor Nikos, who worked most of his life without many honors, persecuted by his own government and Church, and without much money either. The man was a very hard worker with very little love of material reward. He wrote school textbooks, plays, operas, poems, and re-wrote the Odyssey for modern times. He was a good man too. All of this. But I also respect people who try to see things the way they are, not the way they wish they could be. Despite Stalin and the brutalities of Soviet Communism, he traveled through the USSR in the 1920s and found it good. Still in Siberia, he wrote that he was in Manchuria, “in the middle of China”, and found the Chinese scarcely human. He could wax poetic about his African ancestry, of which no proof was ever found. Outside of Europe, he was a lost soul, full of the worship of exoticity, true to his super-romantic soul. Exaggeration and disregard of facts ruled the roost. As he got older, he calmed down somewhat, he was nominated several times for the Nobel, but did not get it; ill health began and he died at the age of 74 in Germany.

By reading this book you will learn a lot about a famous writer, but you’d better like fudge. Disappointingly I found out nothing about the thoughts and writing process that led to his great novels, which are not mentioned till after page 400 and then, only briefly. However, “The Greek Passion” is still one of the best novels I’ve ever read.