What do you think?

Rate this book

345 pages, Kindle Edition

First published July 28, 2020

In the Bible, the apocalypse is not the final battle between good and evil—that is Armageddon, a word derived from an ancient military stronghold on a trade route linking Egypt and the Middle East. An apocalypse is a revelation—literally an uncovering—about the future that is meant to provide hope in a time of uncertainty and fear.The above was quoted from the book. But in Olson’s Twitter feed he offers a slightly different take.

The title is The Apocalypse Factory: Plutonium and the Making of the Atomic Age. To be clear, apocalypse refers to the threat of nuclear war, not to the site itself.Most of us, if asked, could probably identify the Manhattan Project as the national undertaking that produced the atomic bombs used in World War II, and as the Ur prototype for every future absolutely-positively-got-to-do subsequent development drive, to be referred to forever as A Manhattan Project for [insert your national need here]. Many people, certainly those of my (boomer) generation, can easily recall seeing film clips of that first test explosion in New Mexico, and probably later tests that vaporized large portions of Pacific islands. But if we, as a group, were to be asked where the material that fueled those terrible explosions came from, I doubt that a majority would know. It was manufactured, primarily, in Hanford, Washington.

I’ve been getting ready to write this book pretty much my whole life. I grew up in the 1960s in Othello, Washington, a small town in the south-central part of the state just over a ridgeline from a mysterious government facility called Hanford. We knew that Hanford was involved in the U.S. nuclear weapons program. Some people in town knew that it manufactured a substance called plutonium. But it was the Cold War. It was best not to ask too many questions. In 1984 I visited Hanford to write a story for Science 84 magazine, and by the end of the trip, I had decided to write a book about the place. Thirty-six years later, the book is done. - from the NASW interviewThis is a story of war, science, politics and people. It is a story of what was known, what knowledge was needed to move forward, whether known or not, a story of personal ambition and national requirements under the direst of circumstances, a story of patriotism and risk. Yes, we know how it all turned out, but maybe did not know where the turns were that needed to be made to ensure that outcome, maybe had less of an idea about who was involved, what they worked on, where, and why. And maybe did not know what blind alleys were entered before a clear route was constructed.

”I knew that the effort would be expensive, that it might seriously interfere with other war work. But the overriding consideration was this: I had great respect for German science. If a bomb were possible, if it turned out to have enormous power, the result in the hands of Hitler might enable him to enslave the world. It was essential to get there first, if an all-out American effort could accomplish the difficult task.”Even before it was known if a bomb could be made at all, it was known that there were materials that would be needed for it, and at a large scale.

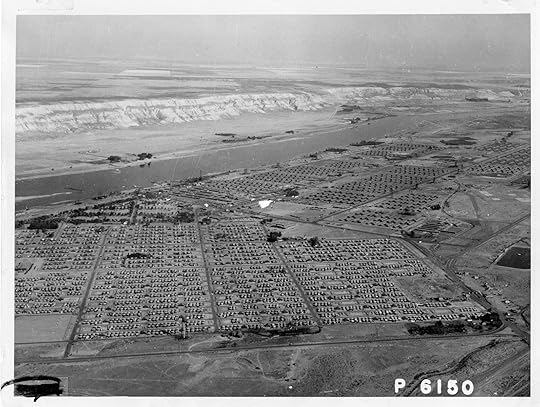

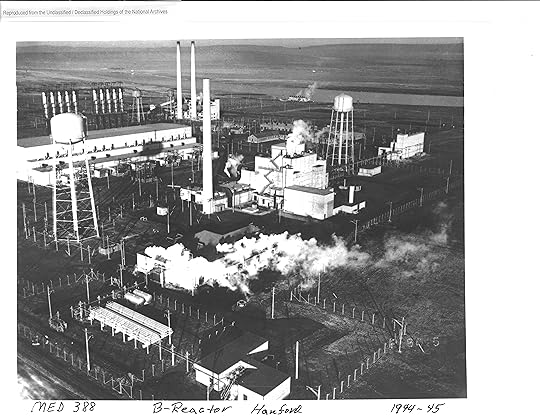

December 16, 1942 found Col. Franklin T. Matthias…and two DuPont engineers headed for the Pacific Northwest and southern California to investigate possible production sites. Of the possible sites available, none had a better combination of isolation, long construction season, and abundant water for hydroelectric power than those found along the Columbia and Colorado Rivers. After viewing six locations in Washington, Oregon and California, the group agreed that the area around Hanford, Washington, best met the criteria established by the Met Lab scientists and DuPont engineers. - from The Atomic Heritage FoundationOlson writes of the displacement of locals that took place. Part of the project entailed housing tens of thousands of new Hanford workers. Five years before Levittown, the United States government built the first standardized suburb. Of course, it came with a surveillance state attached, and provided endless fodder for conspiracy theorists and science-fiction writers with diverse notions of an Oddville sort of place. (All hail the Glow Cloud) He tells of the construction of the first nuclear reactor, and many that followed, and the enormous buildings that were used for chemically extracting plutonium from the product of the reactors. We learn about the environmental degradation that resulted and the eventual acceptance of responsibility for cleaning up. (without, of course, adequate funding to do the job completely, now estimated to require $300 to $600 billion)

The most recent studies indicate that a nuclear exchange of even 50 Nagasaki-type bombs would produce climate changes unprecedented in recorded human history and threaten the global food supply. A large-scale exchange of nuclear weapons would so reduce temperatures that most of the humans who survived the initial bombing would starve. Many people are concerned today that climate change poses a threat to human civilization but the most certain and immediate threat still resides in the nuclear weapons sitting in missile silos, bombers, and submarines around the world.