What do you think?

Rate this book

127 pages, Hardcover

First published October 1, 2009

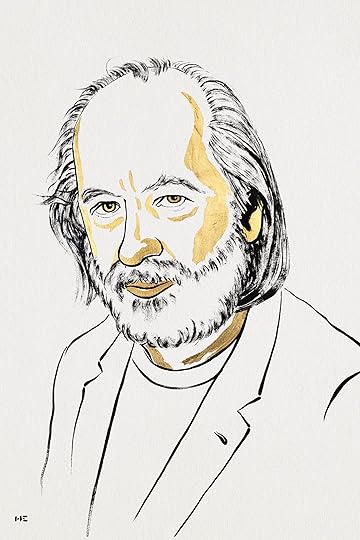

This story by the Hungarian master of the apocalypse, who won the International Man Booker Prize, is about a former German professor who spends his days in a Berlin tavern. He unexpectedly receives an invitation to Extremadura, an isolated and sparsely occupied part of Spain, to write about their potentially prosperous future. However, a strangely worded sentence in an ecological article that he reads in preparation for the trip triggers an unforeseen sequence of events, which leads him to dig further into a search for the last wolf in the countryside. - a translation of the Estonian language synopsis.

his feeling of anxiety was more pressing, more intense, more insistent, than the sense of emptiness that constituted his very being

[he] had written a few unreadable books full of ponderously negative sentences and depressing logic in claustrophobic prose, a series of books in fact… his hopelessly complex, thoughts and sentences.

as soon as you abandoned thought and tried simply to look at things, thought cropped up again in a new form, a form from which, in other words, there was no escape whatever man thought or did not think, because he remained the prisoner of thought either way

[he] had instead locked Extremadura in the depths of his own cold, empty, hollow heart, and that ever since then, day after day, he had been rewriting the end of José Miguel’s story in his head.