What do you think?

Rate this book

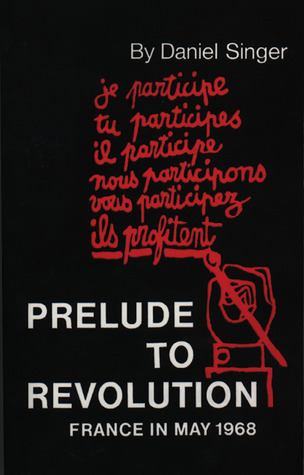

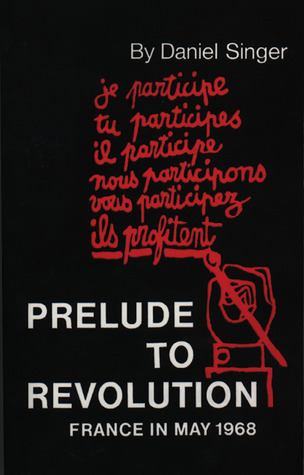

504 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1970

That in most countries five per cent of the population owns three quarters of a nation's wealth, that everything is designed to preserve the interests of this minority, that the owners of capital, their associates, and their servants determine the rhythm of our work, shape our lives, condition the pattern of our behavior — this hardly concealed dictatorship is taken for granted and treated as a realm of freedom. Any outburst against this repressive society is branded as violence.

A gate broken at the London School of Economics, a lecture interrupted at the Sorbonne, a building occupied at Columbia, let alone a factory occupied by the workers- these are subjects for hysterical headlines and bouts of indignation. Violence is not measured by the amount of force used or the degree of coercion exercised. It is measured by its conformity to the law. It is virtue if it helps to prop up the established order, and a horrible vice when directed against it.

Pick up your paper, switch on your television set, and you will find countless examples of such double standards.