What do you think?

Rate this book

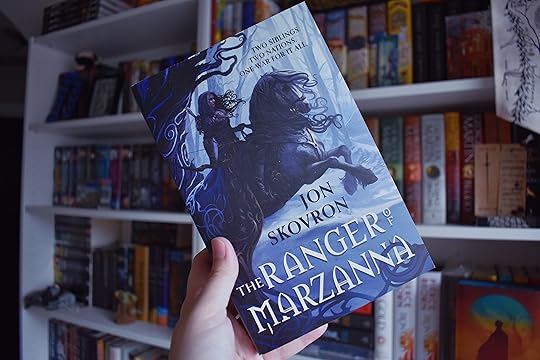

486 pages, Paperback

First published April 21, 2020

“Every father longs to save their child from the suffering they themselves endured. And I won’t lie and tell you there won’t be suffering somewhere along this path. But there is always suffering. On any path. That is an unavoidable part of life, regardless of what you choose to do with it. Suffering is what makes us who we are.”

“Apparently one could survive a jump from sixty feet into a wagon filled with straw, but not without great cost.”

That being said, there’s still a relatively solid foundation beneath the top level issues. The book follows two siblings who have been forced to stand at odds against one another by their different political beliefs. Sonya is committed to liberating her homeland, Izmoroz, by any means necessary. She’s pledged herself to Lady Marzanna, goddess of death, in pursuit of this goal. In exchange for the Lady’s gifts, she finds herself being slowly but surely stripped of her humanity. Each boon the Lady grants comes at a price.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t entirely impressed with how that price was presented. While Sonya has a few brief moments of horror at the way her inner, animalistic nature manifests, it does not seem to impede her day to day life much at all. Generally, it actually helps her. It felt less like a price and more like a change, which I found to be less compelling.

Her brother, Sebastian, has a very different view of how Izmoroz should be run. He’s embraced the empire that conquered them, and has joined their army as a sorcerer. He wields powerful elemental magic. Where Sonya loses her humanity through her magic, Sebastian loses his piece by piece as the empire demands ever more heinous acts from him.

Within the writing, the two characters are differentiated primarily by their mode of speech. Sebastian exists within the upper echelons of society, rubbing elbows with the nobles and upper crust. Their speech is flowery, purple, and frankly feels awkward and forced. I was not a fan. It felt… juvenile. He's supposedly smart, well-read, and intellectual, but repeatedly ignore the subtext of actions and words in real life.

His sister's actions had made reconciliation impossible. But he reminded himself that even if he had lost his sister, and barely recognized his mother in looks or speech, he had a new family: the noble Commander Vittorio, the wily General Zaniolo, the stalwart Rykov, his loyal men, and of course the beautiful and gentle Galina Odeyevtseva, who comforted him when the burdens of leadership grew heavy.

Sebastian's fiancee, Galina, was arguably the most compelling character in the novel. As it progressed, I was pleased to see her get additional screen time. She and her father have been dedicated to preserving Izmorozian culture for ages; although she's not a native resident, she recognizes the horrors of imperialism that have been inflicted on the land. Initially, she views Sebastian as an opportunity to take their conquerers down from the inside with him by her side. Gradually, these hopes are dashed... and she resolves to use her connection with him to betray the empire and support the Izmorozian uprising. She manipulates the other members of the army, hiding behind a facade of feminine naiveté.

"And to what do we owe the rare pleasure of your feminine charms?" he asked.

"Merely a longing to see my beloved. He has just returned from a mission that took him away from me for several days and I simply could not wait until supper to see him. You know how weak willed and impetuous womenfolk can be, General."

Sonya, in contrast with both Sebastian and Galina, spends most of her time among small, rural villages. She’s committed to working alongside the people. Her dialogue is peppered with modern slang and phrases. In text, it’s made clear that this is meant to represent peasant vernacular. For me, though, it felt jarring and out of place. It was a lot like how I speak to my friends. It’s not a way of speaking that I associate with a fantasy world.

If I had been more invested in the characters and better understood their motivations, I think I would have enjoyed their rivalry much more. As it was, it seemed to lack soul. I didn’t really have a particular reason to care much about Izmoroz, didn’t really understand what motivated Sonya, and Sebestian often just seemed like he was awful for the sake of it. This could have been interesting and compelling if the author had dug a little deeper and done something a bit more original than a black-and-white imperialists-vs-natives story.

The Ranger of Marzanna needed a little more depth and a little more polish. It has some great elements, but I regret to say that they don’t quite live up to their potential. On the whole, the book was aggressively mediocre.

More reviews on my blog, Black Forest Basilisks.

Hunters might strike with efficiency, thereby sparing their prey undo pain and suffering, but creatures of the wild did not take into account such things. And certainly Lady Marzanna, Goddess of Winter and Death, was not a creature that could ever be tamed.

She was doing the work she had vowed to do as a Ranger, protecting the people of Izmoroz and undermining the empire that had outlawed the worship of the great Lady Marzanna.

What a terrible thing was love. What a dreadful weapon it could become.

”Just as the fate of all snow is tho melt, the fate of all mortals is to die.”