What do you think?

Rate this book

144 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1965

Perfect worlds do not exist. There are only the funny, strange, weeping, singing, truncated, and imperfect universes created by the gods of paintbrush and musical instruments, the gods who infuse their creations with their own blood, their own soul. When he looks at these worlds, the true Lord of Hosts, the creator of the universe, probably cannot help but smile mockingly.

[...]

We have the right to ask the divine mocker this question: in whose image and likeness was humanity created? In whose image were Hitler and Himmler created? It was not men and women who gave Eichmann his soul; men and women merely made an Obersturmbannfuhrer’s uniform for him. And there were many other of God’s creations who covered their nakedness with the uniforms of generals and police chiefs, or with the silk shirts of executioners.

We should call on the Creator to show more modesty. He created the world in a frenzy of excitement. Instead of revising his rough drafts, he had his work printed straightaway. What a lot of contradictions there are in it. What a lot of typing errors, inconsistencies in the plot, passages that are too long and wordy, characters that are entirely superfluous. But it is painful to cut and trim the living cloth of a book written and published in too much of a hurry.

And so we leave the village.

But when you look at these black and green stones, you realise at once who cut them. The stonecutter was time. This stone is ancient; it has turned black and green from age. What shattered the mighty body of the basalt were the blows struck by long millennia. The mountains disintegrated; time turned out to be stronger than the basalt massifs. And now all this no longer seems like a vast quarry; it is the site of a battle fought between a great stone mountain and the vastness of time. Two monsters clashed on these fields; time was the victor. The mountains are dead, fallen in battle. They have been felled by time just as mosquitoes, moths, people, dandelions, oak and birch are felled by time. Defeated by time, the dead mountains have been turned to dust. Their black and green bones lie scattered on the field of battle. Time has triumphed; time is invincible.

All this leads me to think that this world of contradictions, of typing errors, of passages that are too long and wordy, of arid deserts, of fools, of camp commandants, of mountain peaks coloured by the evening sun is a beautiful world. If the world were not so beautiful, the anguish of a dying man would not be so terrible, so incomparably more terrible than any other experience. This is why I feel such emotion, why I weep or feel overjoyed when I read or look at the works of other people who have brought together through love the truth of the eternal world and the truth of their mortal “I”.

True goodness is alien to form and all that is merely formal. It does not seek reinforcement through dogma, nor is it concerned about images and rituals; true goodness exists where there is the heart of a good man. A kind act carried out by a pagan, an act of mercy performed by an atheist, a lack of rancor shown by someone who holds to another faith -- all these, I believe, are triumphs for the Christian God of kindness. Therein lies his strength.Again and again, I find myself reading passages that are the equal of the best I have read anywhere.

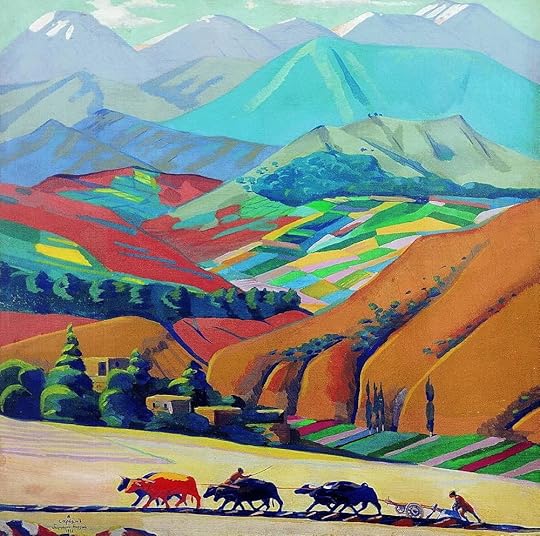

"But the supreme human gift is beauty of soul; it is nobility, magnanimity, and personal courage in the name of what is good. (97)Vasily Grossman possessed this gift. I fell in love with him, to put it dramatically, after reading his magnificent novels Life and Fate and Everything Flows (the former, especially, is very great and far too little read). I decided to read An Armenian Sketchbook next, which is his account of the time he spent in Armenia in 1961, working on a translation of an Armenia novel into Russian. It is a travel diary, memoir, self-portrait, and personal testament all blended together, written shortly before he died of cancer (and perhaps with the knowledge, at some level already, that he would not live long). Grossman recounts his time in Armenia, the people he met there, and the places he visited. The Sketchbook is a touching and personal work; Grossman gets carried away with his descriptions here and there, but he makes up for it with passages of real beauty. His humanity shines through in many places, and some of his reflections left me close to tears; I think it is a rare gift for a writer to make you miss him.