So, midway through the first chapter of this book, I realized that it was probably going to creep me out. Moreover, I resolved to only read it during the daytime, as it was definitely not good preparation for a trip to dreamland. Forget about cinematic zombies and vampires, this book has the real thing, across multiple species, and raises some awkward questions about humans and free will. Not good topics for late night thinking.

The author began with an article on toxoplasmosis gondii, a parasite that has a complex life cycle. It goes from rats, to cats, to cat feces, and then back to rats. Two of these steps are pretty easy, but one of them is harder because rats have a natural instinct to avoid cats. Of course, perhaps a cat will eventually catch it anyway, but perhaps not, and that's a chance that toxoplasmosis gondii is not going to take.

Instead, it alters the behavior of the host rat. Instead of avoiding the smell of cat urine, it begins to seek it out. Obviously, a rat which seeks out the smell of cat urine is a lot more likely to end up eaten by a cat, than one which avoids it. It all makes sense, from the point of view of toxoplasmosis gondii. It doesn't make so much sense from the point of view of the rat, but it appears that toxoplasmosis gondii gets into the brains of their hosts, and alters their neurons in a way to make them act against their own interests.

This is creepy enough, but it turns out that toxoplasmosis gondii are able to live in humans as well. We don't end up eaten by cats all that often (nowadays), but it appears that at least sometimes we end up changing our behavior as well. In addition to impacting our ability to smell cat urine (which is an oddly gender-dependent effect), it alters our willingness to take risks. People with toxoplasmos gondii infections do not normally end up showing obvious signs, but it has been linked to increased levels of depression, suicide, schizophrenia, and even traffic accidents.

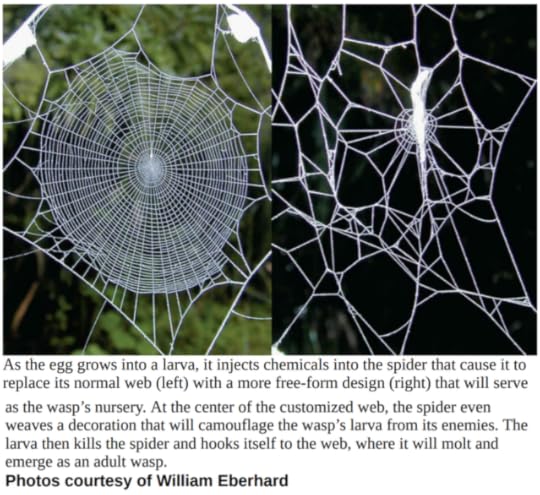

From there, we go on to learn about numerous other parasites that have the ability to manipulate their host's behavior. For example, fungus that makes ants climb up a plant, hang from the bottom side, and then die there with their jaws locked on so that the fungus which sprouts from their body will rain spores down on other ants. Or the wasp that performs brain surgery on a cockroach (admittedly, not a large brain), and then has a compliant zombie which will allow its antennae to be yanked off and will go wherever the wasp steers it to, and stay there. Like, say, in a chamber waiting for the wasp's egg to hatch so the next generation wasp can eat it. It's hard to feel sorry for a cockroach, but that's pretty horrifying.

It gets worse: they are starting to find evidence of more parasites that live in humans, and alter our behavior (hopefully not resulting in any of our limbs being yanked off, though). It gets even worse: with the rapid drop in the price of DNA sequencing, we are able to find out about non-human DNA inside us at an ever-accelerating rate. We may find out about a lot of parasites inside us, that we never knew were there, in the near future. They may live in our gut and make us crave the foods they want, instead of what we should eat. They may do things we haven't even guessed at yet.

Just when you think the book is headed down into a nightmarish melange of uncomfortable science that leaves our concept of free will a bloody pulp, McAuliffe takes a sharp turn, and we start talking about non-parasites. Not everything that lives on us and in us is a parasite, not even if we're just talking about the ones that influence our behavior. Lab mice who are purged of absolutely all microbes, turn out not to be healthier or smarter. Instead, they turn out to be listless, reckless, unable to learn as well, unable to avoid predators. Most of those microbes living inside us do NOT want us to get eaten by a cat, because their lifecycle involves getting passed on to a baby human (or lab mouse, as the case may be), and they need us alive and well to do that.

Then, we go into even stranger ground, and here McAuliffe (by her own admission) is getting a little ahead of the evidence (but not much). There are starting to be more and more researchers looking at whether or not the presence of more or fewer dangerous microbes, has impacted how human cultures evolved. What is the best attitude towards a stranger who shows up? Should marriage outside of the culture you're in be allowed? Is it ok to eat new foods? How should we regard people who travel a lot, and adopt strange practices from other places? McAuliffe thinks it may have something to do with whether there's more or less risk of a new plague showing up with that stranger, or that xenophile from your own tribe who travels abroad and then comes back. The greater the risk of a culture-obliterating parasite), the less the potential payback of new ideas and new friends is worth it. If you don't think it can happen, read up on the fate of the Native American city-based civilizations. Had they been more culturally xenophobic, they might still be here.

Well, maybe. It's certainly an intriguing idea, but lots of intriguing ideas turn out not to be true. On the other hand, the idea that toxoplasmosis gondii can alter human behavior seemed pretty wacky twenty years ago, and it's now been supported by multiple studies in different countries by different researchers. When McAuliffe points out that we are apt to underestimate the impact of microbes simply because they are not seen, I am reminded that much of the history of the clash between Native Americans and Europeans is pretty much beside the point. If every European settler had been peaceful, and every Native American friendly, the end result would have been much the same, because smallpox, measles, cholera, and a host of other diseases didn't want to play nice. It was really the microbes that dictated how the West was won, and the humans involved were mostly just vessels, and all the wars fought between them were sideshows that had little impact on the end result.

So McAuliffe's book may or may not be getting the details right, but the underlying message is surely on target. We may not be paying attention to parasites, but they are paying attention to us, and they have been for a long, long time. It's very likely that we are underestimating their impact.