What do you think?

Rate this book

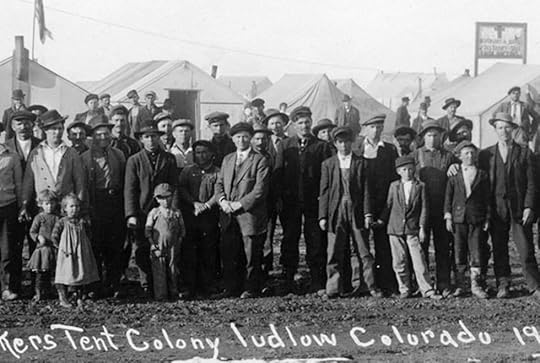

On a spring morning in 1914, in the stark foothills of southern Colorado, members of the United Mine Workers of America clashed with guards employed by the Rockefeller family, and a state militia beholden to Colorado’s industrial barons. When the dust settled, nineteen men, women, and children among the miners’ families lay dead. The strikers had killed at least thirty men, destroyed six mines, and laid waste to two company towns.

Killing for Coal offers a bold and original perspective on the 1914 Ludlow Massacre and the “Great Coalfield War.” In a sweeping story of transformation that begins in the coal beds and culminates with the deadliest strike in American history, Thomas Andrews illuminates the causes and consequences of the militancy that erupted in colliers’ strikes over the course of nearly half a century. He reveals a complex world shaped by the connected forces of land, labor, corporate industrialization, and workers’ resistance.

Brilliantly conceived and written, this book takes the organic world as its starting point. The resulting elucidation of the coalfield wars goes far beyond traditional labor history. Considering issues of social and environmental justice in the context of an economy dependent on fossil fuel, Andrews makes a powerful case for rethinking the relationships that unite and divide workers, consumers, capitalists, and the natural world.

(20090215)386 pages, Hardcover

First published October 1, 2008