What do you think?

Rate this book

208 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2005

‘A song is expansion into the past, a photo is finitude. A song is the happy sensation of time, a photo its tragic side. I’ve often thought that one’s whole life story could be told just with songs and photos.’

‘The horror at the other end of our love, as if the outside world had always to be there, beyond the kitchen window.’

‘I now realize that the only thing that can justify scientific and philosophical endeavor, and art, is not knowing what nothingness is. And if the shadow of nothingness, in one form or another, does not hover over writing, even of a kind most acquiescent to the beauty of the world, it doesn’t really contain anything of use to the living.’

‘I feel there’s nothing we could do together that would be better than this, an act of writing at once united and disjointed. Sometimes it also frightens me. To open up your writing space is more violent than to open up your sex.’

... the material traces of presence

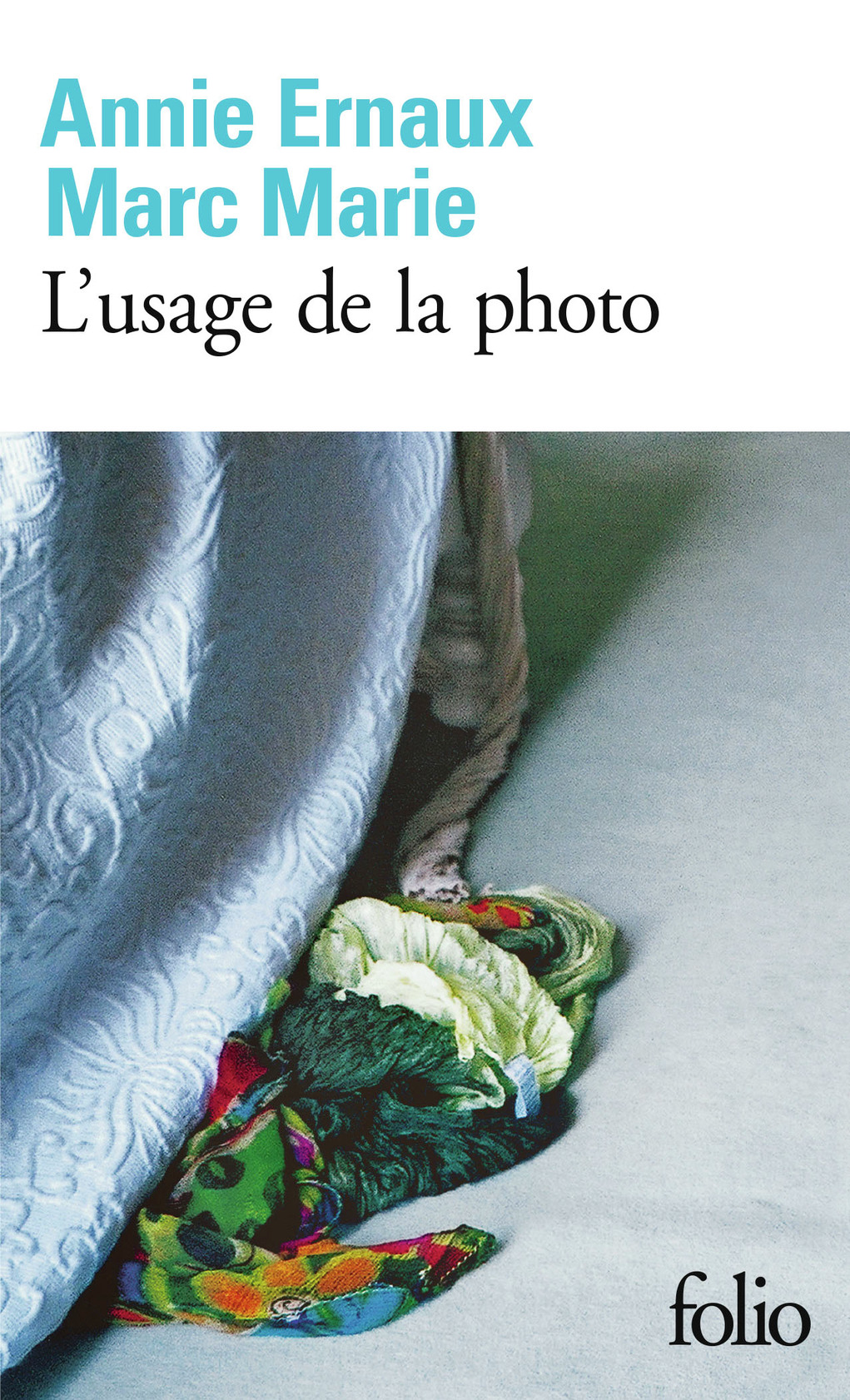

Week after week, the photographs accumulated, several dozen in all. The spontaneous act of taking photos became a matter of ritual. But always, at the moment when I collected my things and destroyed that harmony, my heart sank, as if each time I were desecrating the relics of a sacred place. To us it was as beautiful as a work of art, as remarkable for the play of colours as for the interaction between the different fabrics as if, though immobile for the moment, they were preparing to creep towards each other and perpetuate our gestures. The crime lay not in what we’d done, but in the action of undoing it.

When this photo is taken, my right breast and the submammary fold are a brownish colour, burnt by cobalt, with blue crosses and red lines drawn on the skin to precisely indicate the area and the points to be irradiated. At the same time, I have been prescribed a postoperative chemotherapy protocol that is different from the previous one, and, every three weeks, for five days in a row, even at night, I have to wear a kind of harness, a belt around my waist with a bumbag containing a plastic bottle, in the shape of a baby bottle, filled with chemotherapy products. It has a thin transparent plastic tube coming out of it, ending with a needle stuck into the catheter and covered by a dressing. Strips of adhesive tape hold the tube in place against the skin. Its heat causes the chemo liquids to rise and flow through my veins. Because of the bag on my belly, I cannot close my jacket or my coat, and I have difficulty hiding the plastic tubing attached to the bottle and threaded up under my jumper. When I am naked, with my leather belly, my vial of poison, my multicoloured markings and the tube running across my upper body, I look like an extraterrestrial.

I can no longer abide novels or films with fictional characters suffering from cancer. What possesses those authors, how do they dare to invent these kinds of stories? Everything about them seems fake, to the point of being ridiculous.

Since our arrival on Friday, we’ve been going from place to place in the pouring rain – Uccle, the Bourse, the rue de Midi, the rue du Marché aux Poulets, the Métropole bar, the place de Brouckère – Brussels as I have always known it, not really hostile, just reticent.