What do you think?

Rate this book

159 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1967

Furthermore, his house had no electricity, and its tiny bathroom was so small that when he sat upon the throne-of-thought he could not shut the door without hitting his knees, which was an outrage.

The young vicar suggested the teacher cut two round holes for his knees to stick through, and offered to trade his outhouse for the teacher's bathroom, but the teacher was not amused. There was one more thing he felt it his duty to inform the vicar. The vicar might as well know right now that as for himself, he was an atheist; he considered Christianity a calamity. He believed that any man who professed it must be incredibly naive.

The young vicar grinned and agreed. There were two kinds of naivete, he said, quoting Schweitzer; one not even aware of the problems, and another which has knocked on all the doors of knowledge and knows man can explain little, and is still willing to follow his convictions into the unknown.

"This takes courage," he said, and he thanked the teacher and returned to the vicarage.

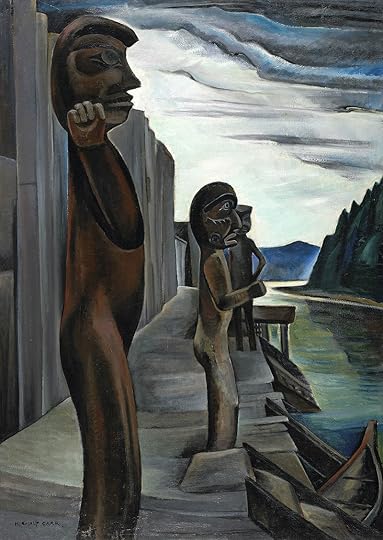

The young vicar stopped his patching and descended the ladder.American author Margaret Craven (1901–80) first heard about the Kwakwaka'wakw (Kwakiutl) culture on the coast of British Columbia from her brother, who had visited there, and arranged with the Columbia Coast Mission of the Anglican Church to see for herself. The immediate result was this short novel, published in Canada in 1967 to great acclaim, and in the US in 1973. In that it is fiction, the story is quietly affecting. But you also see the non-fiction writer building on her travel journal, compiling native legends and traditions, and making a plea for the preservation of a First Nation culture that was quickly being obliterated by the modern world. Both elements have their place, but they do not necessarily combine into a strong novel.

"Chief Eddy," he said earnestly, "there is something I have been meaning to ask you. How do you pronounce the name of your tribe?" It is spelled Tsawataineuk.

"Jowedaino."

There was a silence.

"Would you mind saying it again?"

"Jowedaino," and Mark listened more carefully than he had ever listened to any work in his entire life and could not tell if the word was Zowodaino or Chowudaino.

"And the name of the band to which your tribe belongs?" which in the books of anthropology is written Kwakiutl.

"Kwacutal," and Mark listened and could not tell if the word was Kwagootle, Kwakeetal or Kwakweetul.

"And the name of the cannibal who lived at the north end of the world?"

"Bakbakwalanuksiwae," and it came from the chief's lips like a ripple.

The premise is artificial but effective. A doctor tells a bishop that a young ordinand has less than three years to live, though he does not know it. The bishop decides not to tell the young vicar, in case it should make him try too hard, but sends him to the parish where he feels he will learn most quickly: the village of Kingcome, at the head of the Kingcome Inlet off Queen Charlotte Sound. The young vicar, whose name is Mark Brian, is given an Indian boatman to look after him for the first year. He sails upriver to his new parish, where he finds the people welcoming but both vicarage and church in poor repair. What follows is much like an Anglican version of Willa Cather's Death Comes for the Archbishop moved to the Pacific Northwest. Mark is naive but touchingly humble. For example, when the bishop offers to send him a prefabricated vicarage to replace the old one, he defers, preferring first to make the repairs with his own hands. When the new building does arrive a year or two later, all the men in the village now turn out to help him, for he has won their trust and in all sorts of ways made himself part of their lives.

Approaching Kingcome village

Although Mark is an Anglican vicar, religion is not a major theme of this book, but as much the background to his life as are the forests and mountains surrounding the village. He does not waste time thinking whether the ancient ceremonies and totems conflict with the Christian faith, but celebrates their importance to the tribe. When a young woman returns from the outside world pregnant with the child of her former boyfriend who has decided to remain there, Mark replies, "What you have done is strange to me, but I think I understand it"—which is, of course, to return part of the heritage to the village that gave them birth. Perhaps Mark is too good to be true, and the Biblical simplicity of the writing often reads more like fable than modern fiction, sometimes requiring a little indulgence from the reader.

Kingcome church today

Soon the huge flights of snow geese would fly over the river on their way back to the nesting place, the spring swimmer woulf come up the river to the Clearwater, and on the river pairs of cocky, small, red-necked sawbills would rest, the father flying off when Mark passes and the mother pretending she had broken a wing to lead him awaw from her little ones. And each would feel the pull of the earth and know his small place upon it, as did the Indian in his village.

He went slowly up the river. In front of the vicarage he anchored the boat and waded ashore. He trudged up the black sands to the path and stopped. From the dark spruce he heard an owl call—once, and again—and the questions that had been rising all day long reached the door of his mind and opened it.