Q:

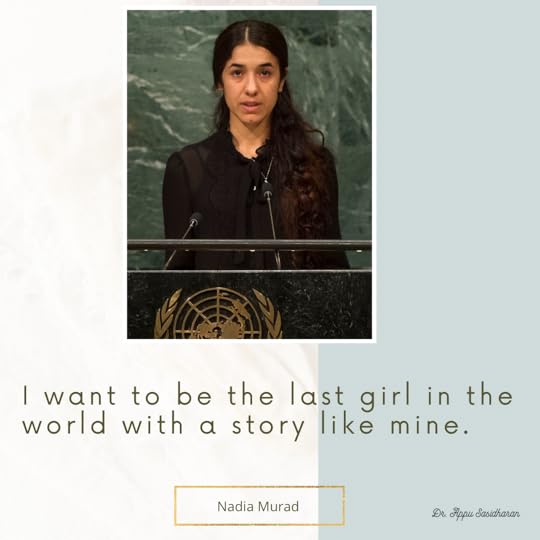

More than anything else, I said, I want to be the last girl in the world with a story like mine. (c)

Horror fic writers have nothing on our contemporaries. This is a story to illustrate it: a story of a girl who went through true horrors and miraculously lived to tell us about it.

We are supposed to be living in an enlightened and modern and advanced and educated and informed world. And... it all amounts to nothing, since most vulnerable people out there remain just that, vulnerable, and fall victims while we go on thinking just how great our modernity is. Newsflash: it isn't. It isn't even all that modern, since in this book we can get a tiny and very redacted and sanitised glimpse of horrors, very ancient ones at that.

Instead, it's plain scary that our supposedly postindustrial and humanistic and diverse and democratic and altogether oh-so-very-enlightened world has allowed such thing from hell as DAESH to happen to our contemporaries. Including young and defenceless girls who have pretty much nowhere to run. Like Nadia.

And the DAESH surely didn't rise from some God-cursed sand in some God-forgotten desert, on their God-forsaken own. I'm not naive enough to believe that. There's no Petri dish anywhere, which would produce grown religious fanatic fighters on its own, without any external input. And the religion is probably only one of the ingredients here, since, well, many people of Islam are peaceful. Seriously, someone somewhere obviously believes it worthwhile to pay for DAESH weapons, to teach them to fight, maybe even to fight alongside them. Of-freaking-course, what ever could go wrong with a bunch of armed militants going around, running slave markets, casually killing and otherwise 'conquering' women, children, mature people and everyone else? Otherwise, these SOBs would've already long since ran out of resources, since they don't do much business or, say, agriculture or create modern weapons or do pretty much anything that could have kept them supplied with weaponry they rely upon. So, WHAT. THE. HELL. This world must be sick.

The language of writing is simple and unaffected which makes the tale even more touching and heartbreaking. This book can be split into the BEFORE and the AFTER. Such a loving and tranquille and even a bit bucolic setting of the life BEFORE (however hard it was, one can feel the author's nostalgia for what once was and what cannot be recreated AFTER) against the crescendo of sorrow and pain and hurt and all the horror of the AFTER. Our world should not contain such AFTERs. We should not allow such things to happen on our planet.

This book should make us all angry and full of shame that we stand and watch genocide and worse, much WORSE, unthinkably WORTH and do nothing or extremely little.

I don't think many of us can even begine to imagine the depth of horror that has happened to all these victims. Even after reading this book, I don't expect we still could be able to understand it all.

One can only hope that this mission and support and faith and God will help Nadia and give her strength to continue in this uneven struggle and maybe, just maybe, there will eventually be the ultimate last girl to have endured such dreadful horrors.

PS. Some fellow readers are feeling it their civic duty to inform me that DAESH is an Islamic group. While I know that, I also have read the book and paid close attention to the author's take on religion. Nadia is very cautious about her views on Islam and makes it clear that her village has had lots of peaceful interaction with Muslims. And while not one of them (or of anyone else!) came forward to help her fellow villagers in the time of dire need, and while the religion is obviously a sore point for most sides involved in this horrible crisis, Nadia is very gracious about Islam. And I respect this point of view and I don't particularly care about religious hate comments/messages.

The author, even after all the torments, understands that this war is not exactly about religion but rather of a perversity of it, and that anything can be distorted into horror, if someone applies to it. If Nadia can be this gracious, the commentators are advised to do their own work on their own empathy somewhere in private!

Q:

Our faith is in our actions. (c)

Q:

It was a simple, hidden life. (c)

Q:

“I don’t know why God spared me,” he said. “But I know I need to use my life for good.” (c)

Q:

The slave market opened at night. (c)

Q:

Along with the farmers, the kidnappers took a hen and a handful of her chicks, which confused us. “Maybe they were just hungry,” we said to one another, although that did nothing to calm us down. (c)

Q:

As lucky as I am to be safe in Germany, I can’t help but envy those who stayed behind in Iraq. My siblings are closer to home, eating the Iraqi food I miss so much and living next to people they know, not strangers. If they go to town, they can speak to shopkeepers and minivan drivers in Kurdish. When the peshmerga allow us into Solagh, they will be able to visit my mother’s grave. We call one another on the phone and leave messages all day. Hezni tells me about his work helping girls escape, and Adkee tells me about life in the camp. Most of the stories are bitter and sad, but sometimes my lively sister makes me laugh so hard that I roll off my couch. I ache for Iraq. (c)

Q:

Yazidism is an ancient monotheistic religion, spread orally by holy men entrusted with our stories. Although it has elements in common with the many religions of the Middle East, from Mithraism and Zoroastrianism to Islam and Judaism, it is truly unique and can be difficult even for the holy men who memorize our stories to explain. I think of my religion as being an ancient tree with thousands of rings, each telling a story in the long history of Yazidis. Many of those stories, sadly, are tragedies. (c)

Q:

There are so many things that remind me of my mother. The color white. A good and perhaps inappropriate joke. A peacock, which Yazidis consider a holy symbol, and the short prayers I say in my head when I see a picture of the bird. (c)

Q:

Yazidis believe that before God made man, he created seven divine beings, often called angels, who were manifestations of himself. After forming the universe from the pieces of a broken pearl-like sphere, God sent his chief Angel, Tawusi Melek, to earth, where he took the form of a peacock and painted the world the bright colors of his feathers. (c)

Q:

This is the worst lie told about Yazidis, but it is not the only one. People say that Yazidism isn’t a “real” religion because we have no official book like the Bible or the Koran. Because some of us don’t shower on Wednesdays—the day that Tawusi Melek first came to earth, and our day of rest and prayer—they say we are dirty. Because we pray toward the sun, we are called pagans. Our belief in reincarnation, which helps us cope with death and keep our community together, is rejected by Muslims because none of the Abrahamic faiths believe in it. Some Yazidis avoid certain foods, like lettuce, and are mocked for their strange habits. Others don’t wear blue because they see it as the color of Tawusi Melek and too holy for a human, and even that choice is ridiculed. (с)

Q:

We treat happiness like a thief we have to guard against, knowing how easily it could wipe away the memory of our lost loved ones or leave us exposed in a moment of joy when we should be sad, so we limit our distractions. (c)

Q:

We treat happiness like a thief we have to guard against, knowing how easily it could wipe away the memory of our lost loved ones or leave us exposed in a moment of joy when we should be sad, so we limit our distractions. (c)

Q:

April is the month that holds the promise of a big profitable harvest and leads us into months spent outdoors, sleeping on rooftops, freed from our cold, overcrowded houses. Yazidis are connected to nature. It feeds us and shelters us, and when we die, our bodies become the earth. Our New Year reminds us of this. (c)

Q:

It took a long time before I accepted that just because I didn’t fight back the way some other girls did, it doesn’t mean I approved of what the men were doing. (c)

Q:

Before ISIS came, I considered myself a brave and honest person. Whatever problems I had, whatever mistakes I made, I would confess them to my family. I told them, “This is who I am,” and I was ready to accept their reactions. As long as I was with my family, I could face anything. But without my family, captive in Mosul, I felt so alone that I barely felt human. Something inside me died. (c)

Q:

Every second with ISIS was part of a slow, painful death—of the body and the soul—and that moment ... was the moment I started dying. (c)

Q:

We were no longer human beings—we were sabaya. (c)

Q:

... although I stayed quiet, fully believing Abu Batat would kill me if I lashed out again, inside my head I never stopped screaming. (c)

Q:

“And so God turned them into stars.”

On the bus, I started praying, too. “Please, God, turn me into a star so that I can be up in the sky above this bus,” I whispered. “If you did it once, you can do it again.” But we just kept driving toward Mosul. (c)

Q:

II was quickly learning that my story, which I still thought of as a personal tragedy, could be someone else’s political tool, particularly in a place like Iraq. I would have to be careful what I said, because words mean different things to different people, and your story can easily become a weapon to be turned on you. (c)

Q:

“Be patient,” she told me. “Hopefully everyone you love will come back. Don’t be so hard on yourself.” (c)

Q:

“We are surrounded on three sides by Daesh!” ... But Kocho was a proud village. We didn’t want to abandon everything we had worked for—the concrete homes families had spent their entire lives saving for, the schools, the massive flocks of sheep, the rooms where our babies were born. (c)

Q:

I cried for Kathrine and Walaa and my sisters who were still in captivity. I cried because I had made it out and didn’t think that I deserved to be so lucky; then again, I wasn’t sure I was lucky at all. (c)

Q:

“I used to think that what happened to my sons was the worst thing a mother could bear,” she said. “I wished all the time for them to be alive again. But I am glad they didn’t live to see what happened to us in Sinjar.” She straightened her white scarf over what remained of her hair. “God willing, your mother will come back to you one day,” she said. “Leave everything to God. We Yazidis don’t have anyone or anything except God.” (c)

Q:

Justice is all Yazidis have now ... (c)