What do you think?

Rate this book

144 pages, Paperback

First published September 1, 1994

The trouble with me, he said, is that I have classical aspirations but a romantic temperament. I not only like but believe in the notion of regular daily work, of there being no question without an answer, no problem without a solution. But when it comes to it I cannot work unless I am fired by a belief in what I am doing, and there are many questions to which I have not been able to find the answer, many works I have started with high hopes and then been forced to abandon because I was unable to find the right solutions or even to decide what such solutions might be like if I should find them. But that is what we have to live with, he said, and got up abruptly and we left the lake and plunged once more into the birchwoods.

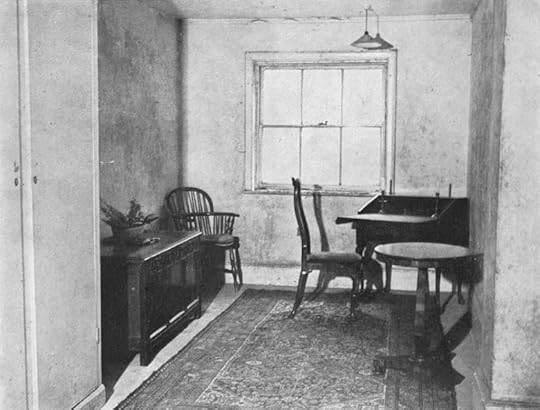

[Swift's:] anger and despair, he said, lay in this contradiction, that he could only speak with ease when he donned a mask and yet he hated the thought of hypocrisy and cowardice and wanted to tear the mask off as soon as it was on. Why I thought of Moor Park as a title, he said, is that, like Animal Languages, it is a contradiction in terms, and I like titles like that. A park is precisely what is not a moor, he said, what has ceased to be moor, nature, and has become park, civilisation. A moor, he said that day in Epping Forest, is nature without boundaries. A park, on the other hand, is precisely the imposition of boundaries, it makes human what was once natural. All books, he said, are moor parks, whether they realise it or not.

A decent conversation, he says, should consist of winged words, words that fly out of the mouth of one speaker and land in the chest of the other, but words that are so light that they soon fly on again and disappear for ever. We don't formulate a thought first and then polish it and finally release it, he said. If we did that we would never get to speak at all. We let it fly, he says, and sometimes it draws something valuable in its wake and sometimes nothing.

Forster and Greene were bad enough, he said, but if their art is not up to much at least it has integrity. Today in the majority of cases our writers have substituted self-righteousness for integrity, they flow with the filthy tide and talk of subversion and risk. It is laughable, he said, to hear them talk on television and in newspaper interviews about how they are vilified and silenced and how the authorities deny them a voice.

But what we have to do, he said as we fled from the Park and the cries of the caged animals and birds, is to live out the contradictions and to see what can be done with them. What I am after, he said as we waited at the bus-stop, is a work which tries to be generous to all contradictions, to place them against each other and let the reader decide. Even that, he said, is the wrong way of putting it. The reader too can only live out those contradictions, cannot adjudicate between them.