What do you think?

Rate this book

220 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1846

χρόνος ανάγνωσης κριτικής: 41 δευτερόλεπτα

Είχα σκοπό να διαβάσω αυτό το βιβλίο όταν θα ήμουν Ρώμη τον

περασμένο Σεπτέμβρη αλλά κλασικά λόγω καθυστέρησης του κούριερ

το διάβασα στην Κύπρο, αφού επέστρεψα από την Ρώμη.

Τουλάχιστον οι ρωμαϊκές μου μνήμες ήταν νωπές ακόμη.

Στη Ρώμη μπήκα την επομένη στα Ιταλικά Public a.k.a. LaFeltrinelli

και πήρα την πλήρη και πρωτότυπη έκδοση των εμπειριών του Ντίκενς

στην Ιταλία του 19ου αιώνα.

Η απορία μου για αυτή την όμορφη αλλά ταυτόχρονα μικρή ελληνική έκδοση

είναι η εξής:

Γιατί να μην εκδοθεί η πλήρης έκδοση αντί μια έκδοση που όχι μόνο είναι

αποσπασματική της πρωτότυπης αλλά είναι και το 1/5 του εκτενέστερου

κεφαλαίου, Ρώμη.

Θα μπορούσε η γραμματοσειρά να μην ήταν αυτή των παιδικών βιβλίων

και να ήταν μεγαλύτερη η έκδοση.

Ίσως ήταν μια δοκιμαστική έκδοση τσέπης για να δουν αν διαβάζεται ο Ντίκενς;

Αλλά αφού διαβάζεται. . .

Τέλος πάντων, το βιβλίο αυτό το συστήνω αν έχετε πάει πρόσφατα ή θα πάτε Ρώμη

και δεν ξέρετε Αγγλικά.

Περιέχει δύο από τις 10 τουλάχιστον εικόνες / εμπειρίες που είχε ο Ντίκενς στην Ρώμη,

την καρναβαλίστικη παρέλαση, και τον αποκεφαλισμό ενός εγκληματία.

Η συνέχεια στην αγγλική έκδοση εδώ.

χρόνος ανάγνωσης κριτικής: 23 δευτερόλεπτα

Σε αντίθεση με την ελληνική έκδοση εδώ,

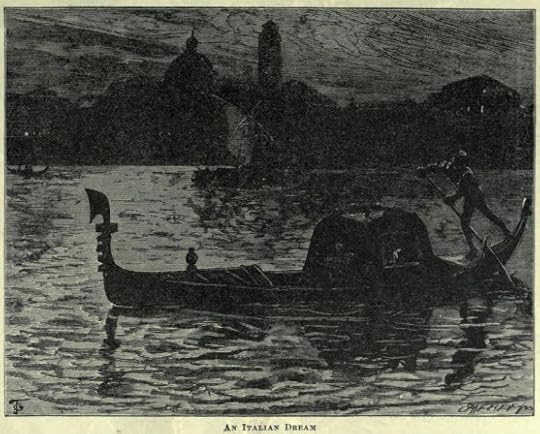

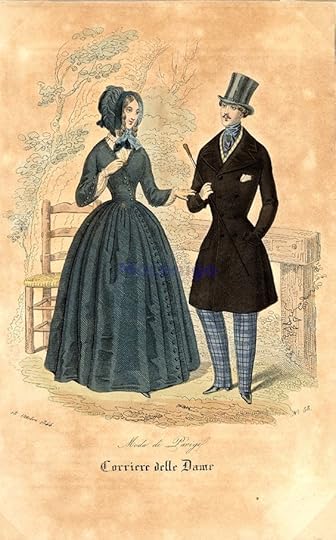

η αγγλική περιέχει εικόνες και από την Φλωρεντία (κούκλα πόλη που επίσης

επισκέφτηκα τον περασμένο Σεπτέμβρη), εικόνες από την Βενετία και την Βερόνα,

που επισκέφτηκα το 2010, όπως επίσης και από πολλές άλλες πόλεις της Ιταλίας,

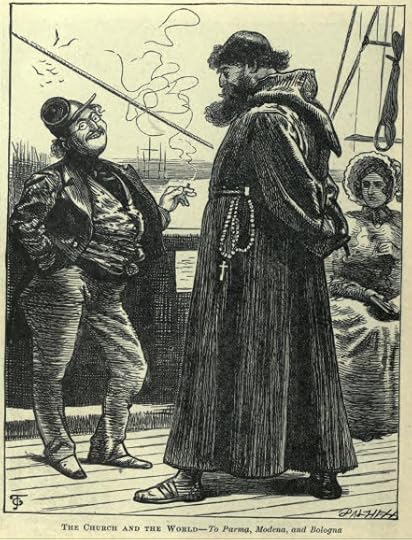

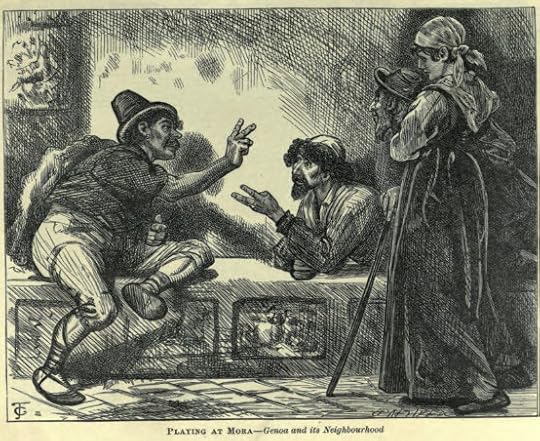

Γένοβα, Πάρμα, Μιλάνο, Νάπολη, Πίζα Πάδοβα, Μπολόνια κλπ.

Εξού και ο τίτλος: Εικόνες της Ιταλίας αντί Δύο εικόνες της Ρώμης

No offence, αλλά παρόλο που είναι πολύ παλιότερός του, η γραφή του Ντίκενς

είναι πολύ πιο ενδιαφέρουσα από του Καζαντζάκη η οποία όπως έχω ξαναπεί

είναι τίγκα στη φιλοσοφία αντί να μας ταξιδέψει με εικόνες των τόπων που πάει.