What do you think?

Rate this book

208 pages, Hardcover

First published September 14, 2017

‘—somebody compared the eclipse to the state of the arts in our country; somebody said that children conceived during an eclipse were born with birth defects or just flat-out evil, which meant that it wasn’t a good idea to make love during an eclipse, total or partial. Then it was time to pay and we all dug into our pockets. As usual, somebody was out of cash, or didn’t have enough, or hadn’t brought cash with him, and among all of us, democratically, we had to cover what he’d ordered, a beer, a coffee, a dish of pineapple preserves. Nothing very expensive, as you can see, though when you’re poor anything that isn’t free is expensive.’

‘(From Lola Fontfreda to Rigoberto Belano) I’m Catalan. I’m an atheist. I don’t believe in ghosts. But yesterday Fernando came to me in a dream. He stood beside my bed and asked me to take care of the child. He asked me to forgive him for leaving me nothing. He asked me to forgive him for not loving me. No. He asked me to forgive him for loving me less than he loved books. But the child made up for all that, he said, because he loved him more than anything. Both of them: Didac and Eric. Actually, the children are what he said, which could have been a reference to all the children in the world, not just his own children. Then he got up and went into another room. I followed him. It was a hospital room. Fernando undressed and got into one of the beds. The other beds were empty, though the sheets were rumpled and in some cases shockingly dirty. I went to Fernando’s bed and took his hand. We smiled at each other. I’m burning up, he said, feel my forehead, how high is my fever? One hundred and seven, I answered. I don’t know why, since there was no way to take his temperature. You’re so precise it’s scary, he said, but now you should go—When I went out, I started to cry. I think Fernando was crying too. From here a person can go back anywhere, he said, please don’t come in—Then I woke up. I was shaking and soaked in sweat. It took me a while to realize that I was crying too. Since I couldn’t sleep anymore, I decided to write this. Now I think I should send it to you.’

‘To speak of Roberto Bolaño’s novels and stories as fragmentary—I’ve done so myself, I admit—is inexact, since each fragment relies on a whole in constant motion, on a genuine process of creation that at the same time is the consolidation of a universe. And precisely because these fragments (like Bolaño’s characters) are in constant motion and because they always lead us back to the larger body of his work—’ (from ‘Afterword’)

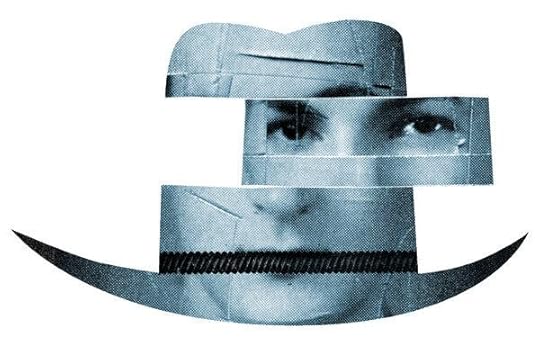

life takes many turns, mr. belano, the adventure never ends...pulled from the late chilean's archives, cowboy graves (sepulcros de vaqueros) collects three novellas: "cowboy graves," "french comedy of horrors," and "fatherland." bolaño's works are all intertextual and referential and overlapping for the most part, and so it is with these three shortish pieces, most likely to appeal to completists and/or anyone who's already read most of his other works, both major and minor.

the silence, as i was saying, is almost total. every so often there's a bit of news, not in the papers or on television, but in magazines, like stories about flying saucers. we know it exists, but the reality is so awful that we'd rather pretend we don't. that's human progress. assaults on a deserted street are awful at first, and break-ins are even worse, but we end up coming to terms with both. we've progressed from the perfect execution to the concentration camp and the atomic bomb. we seem to have stomachs of steel, but we're not ready to digest child-killing cannibalism, despite the counsel of swift and dupleix. we'll accept it eventually, but not yet.