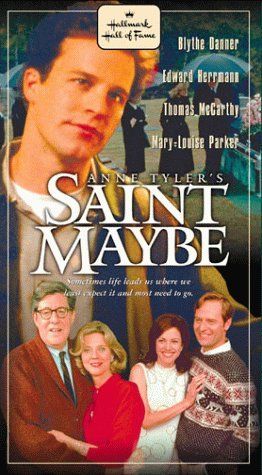

Anne Tyler's book opens with a description of a place: Waverly Street in Baltimore, Maryland. Everyone knows everybody else because this is 1965. We zoom down and look in on the Bedloe family, Bee and Doug, teachers and parents of Danny, Claudia, and Ian, living in a large two-story house on a street full of 'squat clapboard houses' shaded by mostly maple trees.

Ian is 17, and he will soon make a pair of decisions, both of which will haunt him for the rest of his life. One was to tell his older brother, Danny, his suspicions about Danny's new wife, Lucy. This turns out rather ambiguously if you ask me, but Ian believes he is solely responsible for the following tragedy. This leads him into anguished responses of monumental, for him, consequences.

"There was this about the Bedloes: they believed that every part of their lives was absolutely wonderful. It wasn't just an act, either. They really did believe it. Or at least Ian's mother did, and she set the tone."

This doesn't mean bad decisions and tragedies pass the family by. However, it means they have a very useful tool when meeting adversity and bad luck and bad decisions: resilience.

I loved this book. I teared up in several spots. It's definitely a 'feel good' novel. But it is not a shallow cheerful cartoon about people demonstrating rigid moral principles and righteous celebration when vindicated. A touch of saccharine, a bit of fortunate coincidences, a side of smooth friendships - this isn't a book of menacing disasters. But it's nuanced and real, a middle-class American family balancing their personal needs with those of their immediate relatives. The balancing between sacrifice and selfishness is difficult and emotionally stark, but it slowly becomes apparent there are rewards whatever the choice if tempered with positive creativity, more selflessness than selfishness, along with internal strength; and minimum abnegation and resentment.

There are shallow people who never seem to dig deep, and unlikely heroes who save the family with simple formulas - an easygoing religious faith, an acceptance of responsibilities both just and unjust, and a willingness to allow people to fail and make mistakes while keeping the doors open to assist when required. Knowing when to take charge, and knowing what to do isn't always clear, but I think Tyler believes that flexibility along with moderate emotionalism goes a long way to fixing most problems over time. The message here is 'Can-do' expectation works best especially with a forgiving personality, even better than self-examination and space to grow, although those work well later for those able to do so. A drowning individual needs immediately a life preserver, whether that be from a kind, supportive preacher with a list of harmless suggestions (not commandments) or aging, supportive parents with a home but losing ground physically, more than a philosophical discussion about life, gods, morality and predestination. Not everyone has the luxury or intellectual skill set for self-examination. Sometimes simply looking into the faces of your family, dependent on your good will, is motivation enough to do your best at helping and getting them what they need.

A good lesson from this book is, don't overthink it. Just do it, harm no one and be positive. Don't underrate any support group you can gather around you, but be sensible about their help, keeping in mind that what works for you may not work for others.

After all that, did I mention this is a good read? Ahem.

What is our responsibility to other people? When we feel guilty about an error of judgement on our part (if it was an error, or if was it an error of ours that mattered) what do we do to make amends? Feeling guilty is often a guide, but experience and introspection can expose that the feelings we have may not match the event at all, or even if the event can ever be parsed out. Many people cannot or will not examine events, preferring to skim the surface and hope for escape. Some look for a way to ease the feelings with as little introspection as possible, wanting to do the right thing.

Is love enough or is elbow grease and shaping required? What is our purpose in being alive? Is our purpose what we choose or is it chosen for us? Do we choose to make place, duty and family to be important? Do we allow people to fail under the weight of their mistakes? How do we know what the correct responses to these questions should be? Where do step in and take control and where do we back off? Anyone who has a family is faced with these mysteries on a daily basis, and sometimes it matters and often we make no difference at all in the end whatever our responses.

Perhaps an answer, perhaps the best one, is to concentrate on beginning with a good foundation, as if creating a piece of furniture. First, the carpenter knows to build a lasting work he must choose a solid long-lasting wood, such as cherry, and then he must shape it with a competent sensitivity, working with the natural characteristics of the individual wood. As the years pass, it must be maintained by steady perseverance by a responsible owner, by dusting and cleaning and waxing. The most superior piece of furniture will rot over time if not maintained, as any carpenter knows.

Anne Tyler definitely knows.

In a dysfunctional family, per Wikipedia:

List of unhealthy parenting signs which could lead to a family becoming dysfunctional:

Unrealistic expectations

Ridicule

Conditional love

Disrespect; especially contempt

Emotional intolerance (family members not allowed to express the "wrong" emotions)

Social dysfunction or isolation (for example, parents unwilling to reach out to other families—especially those with children of the same gender and approximate age, or do nothing to help their "friendless" child)

Stifled speech (children not allowed to dissent or question authority)

Denial of an "inner life" (children are not allowed to develop their own value systems)

Being under- or over-protective

Apathy "I don't care!"

Belittling "You can't do anything right!"

Shame "Shame on you!"

Bitterness (regardless of what is said, using a bitter tone of voice)

Hypocrisy "Do as I say, not as I do"

Unforgiving "Saying sorry doesn't help anything!"

Judgmental statements or demonization "You are a liar!"

Either little or excessive criticism (experts say 80–90% praise, and 10–20% constructive criticism is the most healthy

Giving "mixed messages" by having a dual system of values (i.e. one set for the outside world, another when in private, or teaching divergent values to each child)

The absentee parent (seldom available for their child due to work overload, alcohol/drug abuse, gambling or other addictions)

Unfulfilled projects, activities, and promises affecting children "We'll do it later"

Giving to one child what rightly belongs to another

Gender prejudice (treats one gender of children fairly; the other unfairly)

Discussion and exposure to sexuality: either too much, too soon or too little, too late

Faulty discipline (i.e. punishment by "surprise") based more on emotions or family politics than established rules

Having an unpredictable emotional state due to substance abuse, personality disorder(s), or stress

Parents always (or never) take their children's side when others report acts of misbehavior, or teachers report problems at school

Scapegoating (knowingly or recklessly blaming one child for the misdeeds of another)

"Tunnel vision" diagnosis of children's problems (for example, a parent may think their child is either lazy or has learning disabilities after he falls behind in school despite recent absence due to illness)

Older siblings given either no or excessive authority over younger siblings with respect to their age difference and level of maturity

Frequent withholding of consent ("blessing") for culturally common, lawful, and age-appropriate activities a child wants to take part in

The "know-it-all" (has no need to obtain child's side of the story when accusing, or listen to child's opinions on matters which greatly impact them)

Regularly forcing children to attend activities for which they are extremely over- or under-qualified (e.g. using a preschool to babysit a typical nine-year-old boy, taking a young child to poker games, etc.)

Either being a miser ("scrooge") in totality or selectively allowing children's needs to go unmet (e.g. father will not buy a bicycle for his son because he wants to save money for retirement or "something important")

Disagreements about nature and nurture (parents, often non-biological, blame common problems on child's heredity, when faulty parenting may be the actual cause)

This list is so dismal, I hate copying it here, but I do so to contrast what a relief it is to read 'Saint Maybe', a book about a functional family which shows how things can be if parents and children avoid the above behaviors. If this suggests to you that there are occasions when reading this novel won't suit your mood, you are right. This novel is about a family which has problems and distresses, but a few key family members pick up the family from its knees during bad and sad times and save the future. No explosions, no psychopaths, no deadly forces or economic displacements.

"Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." From Anna Karenina, by Leo Tolstoy.

"The Anna Karenina principle describes an endeavor in which a deficiency in any one of a number of factors dooms it to failure. Consequently, a successful endeavor (subject to this principle) is one where every possible deficiency has been avoided." -Wikipedia

This is a book where deficiencies are avoided, where being unhappy is solved. I did not find it unreasonable or sappy in the slightest, however. Instead, it seemed to me entirely within the realm of realistic success by families who are both lucky and of moderate expectations.

Happy reading!