What do you think?

Rate this book

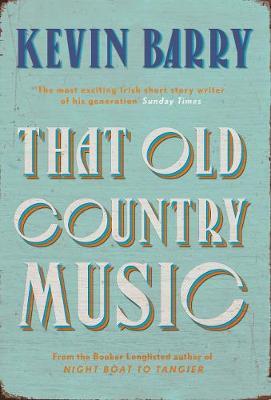

187 pages, Kindle Edition

First published October 15, 2020

The writing was going tremendously. I was due to deliver my third novel. The central philosophy underpinning all of my work to date was that places exerted their own feelings — nonsense, of course, half-thought-out old guff that sounded okay at literary events but now, here in Aldo’s cottage, there was incontrovertible evidence that it was the case. In this place I was calm, lucid, settled in my skin, and apparently ravishing . Elsewhere I was, as ever, a bag of spanners.~ Old Stock

Seamus Ferris could bear a lot. In fact, already in his life he had borne plenty. He could handle just about anything, he felt, shy of a happy outcome.

It was the idea of him rather than the fact — the idea of a long, thin, sombre man, in a soak of noble depression, smelling of lentils, in a damp pebbledash bungalow, amid a scrabble of the whitethorn trees, a man ragged in the province of Connacht and alone at all seasons, perhaps already betrothed to a glamorous early death, and under some especially mischievous arrayment of the stars he was all that a girl could ask for.

The Canavans — they had for decades and centuries brought to the Ox elements that were by turn very complicated and very simple: occult nous and racy semen.

Love, we are reminded, yet again, is not about staring into each other’s eyes; love is about staring out together in the same direction, even if the gaze has menace or badness underlain.

The moving sea gleamed; it moved its lights in a black glister; it moved rustily on its cables.

Why are you so drawn to it? To death? Why are you always the first with the bad news? Do you not realise, Con, that people cross the road when they see you coming? You put the hearts sideways in us. Oh Jesus Christ, here he comes, we think, here comes Who’s-Dead McCarthy. Who has he put in the ground for us today?

There were times of great change beyond the woods, but it did not matter, and the noises of the towns sometimes grew frantic — it did not matter; she read her books — and there were times of mobbed voices and great migrations — it did not matter — and there was the time of the fires across the lakes — it did not matter — and the gaseous blue of their after-glare, but all of it soon faded again and passed, and did not matter.

I used to be afraid of the dogs but they got used to me. Ever the more so as I walk I take on the colours and notes of the places through which I walk and I am no longer a surprise to these places. My once reddish hair has turned a kind of old-man’s green tinge with the years and this is more of it. What the ramifications have been for my stomach you’re as well not to know. I have very little of the language, even after all this time, but the solution to this is straightforward — I don’t talk to people. This arrangement I have found satisfactory enough, as does the rest of humanity, apparently, or what’s to be met of it in the clear blue mornings, in the endless afternoons.

She looked out across the high fields. Just now as the cloudbank shifted to let the sun break through the whitethorn blossom was tipping; the strange vibrancy of its bloom would not tomorrow be so ghostly nor at the same time so vivid; by tacit agreement with our mountain the year already was turning. The strongest impulse she had was not towards love but towards that burning loneliness, and she knew by nature the tune’s circle and turn — it’s the way the wound wants the knife wants the wound wants the knife.

By the time they get you in the bughouse, usually, the worst of it is over. His left hand rests on his fat belly to feel out each breath as it moves through his ribs and eases him. His right hand lies limply by his side but the index finger is busy and scratches quick patterns on the grey starched sheet — it makes words.