Did you know Charles Dickens wrote travelogues? No? Well you’d be right—he didn’t! At least, not in the sense we mean now.

Pictures from Italy is classed as “Travel Literature”, although “Travel Fiction” might be better. It enables us to see into the mind and personality of Charles Dickens, just as the fictional “David Copperfield” is a version of his autobiography. The preposition “from” rather than “of” in the title is significant. These are impressions jotted down at the time, not sober reflections afterwards—and certainly not pretty portraits for a coffee table book.

Charles Dickens set his novels and stories in places he knew well: Great Britain, America, Italy, Switzerland or France. The factual pieces he wrote about other countries are styled like his fiction. They are personal, quirky and opinionated; and no more so than in Pictures from Italy. In no sense are they travel guides to a country, intended to help tourists. There was a plethora of such worthy guides for Victorians who wished to do “The Grand Tour” of Europe, but Charles Dickens was rather contemptuous of these instructive manuals: those reference guides to buildings and works considered to be of artistic merit, writing:

“If you would know all about the architecture of this church, or any other, its dates, dimensions, endowments, and history, is it not written in Mr Murray’s Guidebook, and may you not read it there, as I did?”

A few years later, when writing “Little Dorrit”, between December 1855 and June 1857, Charles Dickens was to draw on his memories of his Italian travels. He even included a wickedly funny character called “Mrs General”. Full of airs and graces, she was forever quoting from “Mr Eustace”: another writer of these essential manuals for every fashionably cultured person. John Chetwode Eustace was an Anglo-Irish Catholic priest and antiquary, who had travelled through Italy with three pupils in 1802. The journal which he wrote during his travels, “A Classical Tour Through Italy” made him famous, and his subsequent “Classical Tour” of 1813 was an instant success. He became quite a celebrity, and a prominent figure in literary society, producing what was viewed as a sort of bible for the Arts.

However, you can almost see Charles Dickens snubbing his nose at this type of writing. He never accepted another’s opinion of what was essential viewing for every educated, civilised person of good taste, or even which works of Art were worthy. Charles Dickens had no compunction about scoffing at paintings, statues or frescoes others might venerate. His life was a quest to get at the truth in all things; challenging what seemed false for any reason, and revealing what lay beneath the surface. His own observations about a country are not refined and in good taste; they are reactive, and full of violent contrasts.

Pictures from Italy began life in 1844. Charles Dickens’s most famous work “A Christmas Carol” in 1843 had been the wonderful success he had hoped for, and he was hugely popular with the public. But it had not earned him the money he sorely needed, after the poor sales of “Martin Chuzzlewit” so far. His publishers had been chary of producing the lavish volume he wished, to match the story he knew was something special. So he had invested his own money in ensuring the books were as beautiful as he wanted them to be. Arguing with his publishers, he financed gold-tooled lettering and gilt-edged pages.

He ended up only making a quarter of what he expected with this first publication of “A Christmas Carol”, and the subsequent piracy and lawsuits meant that he struggled to stay above water financially for a few more months. So after “Martin Chuzzlewit”’s final installment in June 1844, Charles Dickens took a break to recoup his energies, and meanwhile live somewhere more cheaply than London. In fact he did not begin writing novels again for over 2 years, with “Dombey and Son” beginning in September 1846.

Initially for several months, the Dickens family travelled through France and Italy, by coach. They visited the most famous sights, eventually settling in Genoa. First Charles Dickens rented the “Palazzo Bagnerello”, and then he took a villa on a hill, called the “Palazzo Peschiere” (Palace of the Fishponds) for 12 months as a base. He describes it “stand[ing] on a height within the walls of Genoa, but aloof from the town”. Although he liked Genoa’s grand palaces, Charles Dickens was always aware of the dreadful extremes of rich and poor:

“the rapid passage from a street of stately edifice, into a maze of the vilest squalor.”

This is where he wrote “The Chimes”, prompted by the cacophonous chorus of Genoese bells, which assaulted his ears it drifted up the hill to the villa.

Charles Dickens went to Rome, visiting St. Peter’s Basilica, “the great dream of Roman churches” but was disappointed by the centre of Rome, which he found to be like any modern European city:

“When the Eternal City appeared, at length, in the distance, it looked like—I am half afraid to write the word—like LONDON!! There it lay, under a thick cloud, with innumerable towers and steeples, and roofs of houses, riding up into the sky, and high above them, all, one dome.”

Expecting by now desolation and ruin: a certain romantic decaying grandeur, Charles Dickens felt dislocated and discomposed. He even said he preferred decay to classic tourist sites, growing more and more gloomy as they approached Naples, a city of:

“Polcinelli and pickpockets, buffo singers and beggars, rags, puppets, flowers, brightness, dirt and universal degradation”,

where Vesuvius was still smouldering in the background, visiting Florence and the:

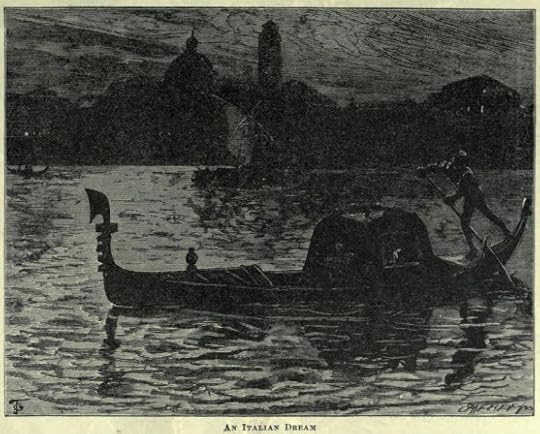

“phantom streets which are canals, and … buildings made by fairy hands”

of dreamy Venice. Almost drunk by the beauty surrounding him in Venice, he expressed himself as all but in a dream, watching pictures repeatedly dissolve into other pictures like a magic-lantern show. Eventually the family returned to England through Switzerland.

Charles Dickens sent letters home to his close friends such as John Forster from all these places. Two years later, he assembled the letters, and they were published for the first time between 21st January and 11th March 1846, as “Travelling Letters, Written on the Road” in the “London Daily News”. There was also an American edition, in two separate magazines under the same title. He then published a slightly edited version as Pictures from Italy later the same year.

He commissioned a young artist called Samuel Palmer (later to become famous) whose sketches he admired, to draw fine vignettes to illustrate Pictures from Italy, for a fee of twenty guineas. Samuel Palmer produced four small illustrations, depicting the Colosseum, the Villa d’Este at Tivoli, a street of tombs in Pompeii and a vineyard scene. The drawings are very delicate, and reflect Charles Dickens’s own perception of the country as a land of disintegration and decay, associating past ruins with the desolation of the present rather than the grandeur of antiquity.

In the first part, “The Reader’s Passport”, Charles Dickens explains:

“This Book is a series of faint reflections—mere shadows in the water—of places to which the imaginations of most people are attracted in a greater or less degree, on which mine had dwelt for years, and which have some interest for all. The greater part of the descriptions were written on the spot, and sent home, from time to time, in private letters.”

This section is almost an apologia for what is to follow, much as Charles Dickens’s “Prefaces” were to each of his novels. The Italy of 1844 was a very different country from Victorian Britain. Charles Dickens had left behind a bleak industrial wasteland. Victorian England was thrust into the beginning of the industrial revolution, when everything was in upheaval, with the building of the railways, the factories, the new housing and so on. What he found on the continent however, was very different.

Italy was a region more than a country. It was partitioned between Austria, the Papal States, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and other small kingdoms, and its reunification would not occur for more than twenty years in the future. It was a troubled region, with years of political domination by foreign powers, and internal divisions. The industrial revolution had not yet reached Italy, and this shocked Charles Dickens, but it also made him aware of what would soon be lost in the march of industrialisation.

He describes Italy’s cities, with their ancient monuments and grandiose buildings, as decaying and decrepit; mere ghosts of their former glorious past. Yet he delights in the colourful customs and people he meets and observes, revelling in the fact that they enjoyed a vibrancy of life which had for the most part disappeared in the industrial society in the England he knew. There is great poignancy in this juxtaposition, and we feel Charles Dickens’s inner struggle; his joy in the moment, yet despairing of the loss of history, and almost fearing what was to come. And there was another dimension which comes through very strongly.

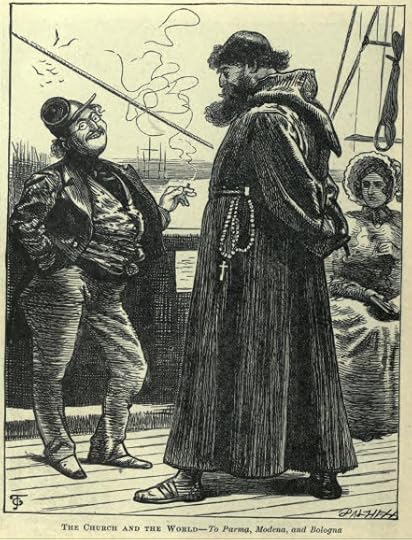

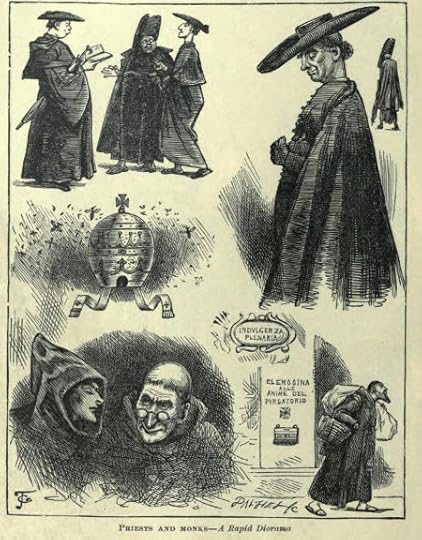

At this time, Protestants in England and other European countries tended to looked down on the Roman Catholic Italians. Charles Dickens was not intolerant in this way; although his own leanings were low church, Pictures from Italy is generally a celebration of the Italian people. Yet some parts could be misunderstood, as he repeatedly ridicules and pours scorn on the pompous clerics, and glittery, tawdry trappings, the:

“sprawling effigies of maudlin monks, and the veriest trash and tinsel ever seen”.

Charles Dickens had no regard for ceremony and was keen to point up what he saw as a vast hypocrisy, with the desperately poor Italians kowtowing to the immensely rich and powerful Catholic church. The avariciousness of the institution is a constant theme. Time and again, he will view a beautiful cathedral, “drowsy Masses, curling incense, tinkling bells”, statues of the Saints and shrines to the Virgin right next to dirt, poverty, beggars and squalor.

Yet Charles Dickens felt a residual doubt that he would be misunderstood in conveying some of his notes, and stressed that he was not criticising conscientious Catholics and their Faith, which he respected. Nor was he criticising the Italian government (although he did so elsewhere), but only reporting what he had seen for himself in practice. He goes on:

“I have likened these Pictures to shadows in the water, and would fain hope that I have, nowhere, stirred the water so roughly, as to mar the shadows.”

And to be sure to get the reader on his side, he sketched a chart: a droll portrait of his desired reader, as “Fair, Very cheerful, Not supercilious, Smiling, Beaming and Extremely agreeable.”

Charles Dickens was a restless traveller, always seeking more:

“It is such a delight to me, to leave new scenes behind, and still go on, encountering newer scenes.”

And such scenes! Never will I forget the image of Charles Dickens on his knees, shuffling up the Holy Staircase in Rome, and his sly but hilarious observations of his fellow shufflers. Or his awe at the great sheets of fire streaming forth from the crater of Vesuvius, sending red-hot stones into the air, before sliding on his situpon—not down the ashes, but down the smooth icy slope of Mount Vesuvius—aware that his clothes were alight, (and also that even an experienced courier had recently slid to his death in the same way). Or his powerful and grotesquely bloody description of scenes or torture by the Inquisition.

It feels as if he is trying to make sense of the extremes of Italy; on the one hand such beauty, on the other a savage, almost unimaginable cruelty. They would not leave him alone, these mental images, and he places the horrific scenes in our minds too. We are aware throughout, as we are entertained, of Charles Dickens’s conflicted views about Italy. Never will I forget his loathing for the village of Fondi, where:

“a filthy channel of mud and refuse meanders down the centre of the miserable streets, fed by obscene rivulets that trickle from the abject houses”

He notes its hollow-cheeked and scowling people, their:

“bad bright eyes glaring at us, out of the darkness of every crazy tenement, like the glistening fragments of its filth and putrefaction”

with near-naked beggarly children scampering around, fascinated at the sight of themselves reflected in Dickens’s shiny coach. And where the incessant demands for money from all sides made Charles Dickens feel he had switched places, from being the observer, to being the one observed.

He approached the subject in the same way that he approached the characters in his novels. They too were frequently taken from life. Sometimes a dozen or more characters in Charles Dickens’s novels are embellished little portraits of his friends, family, acquaintances or well-known personages. No holds barred, he waspishly used his pen to write as entertaining a picture of them as he could.

Sometimes it is better if you do not recognise a famous celebrity of his time when reading, because if they were notorious, then you will have a good idea of what is going to happen to them in his novel! The opposite case can also be made however, that a character portrait for instance of his mother, father, erstwhile sweetheart and so on, can add greatly to a reader’s enjoyment. It enriches the novel, and adds insight into the author’s mind.

So what is the relevance of that here? It is twofold. Firstly Charles Dickens often imbues the buildings and locations—even the furniture in his stories—with human characteristics. He uses personification more than any other author I know. In a scene where another author might write a description of a beautifully decorated or squalid room, Charles Dickens will tell how the room itself feels smug, because it is tastefully decorated at the height of fashion. Or that a roof on a crumbling building is lopsided, and trying desperately to hold on. Or you may find that you start to feel sorry for a creaky, moth-eaten old chair, because he has described it as woebegone. Or as here:

“Queer old towns, draw-bridged and walled: with odd little towers at the angles, like grotesque faces, as if the wall had put a mask on, and were staring down into the moat;”

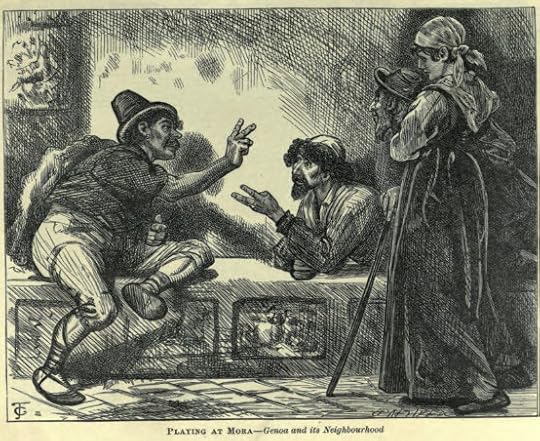

The second point leads on from this. Charles Dickens zooms in on the detail. Whereas most authors of factual works feel an obligation to provide a setting, he will only do so if he thinks it is interesting. Often it will be a cursory sentence or two, before he focuses on what he really wants to say. Perhaps it is the poverty of a certain village, or the untrustworthiness of the inhabitants, or the generosity of other simple folk. He describes performances of street theatre drolly, in great—and hilarious—detail. He is ghoulishly distracted by the death-carts, and will poke fun at the pomposity of a town’s officials, rather than tell you anything about its famous monument. He does cover immense churches, dungeons, prisons, panoramic mountain views, and delightful rustic villages. But just as easily as I have gone into predictable stereotypes just there, Charles Dickens will studiously avoid them.

He will go off at a tangent into history, making us feel sorry for the tragic fate of all the oxen, savagely beaten and worked to death, to carry massive slabs of Carrera marble up the rivers and hills, so that fashionable people may be able to line their hearths and decorate their rooms with beautifully worked pieces. Or he will talk to the prisoners, captive for years in the dark,without basic necessities, and reflect on the previous horrors of torture in the dungeons. He conjures up such a vivid picture, that alongside him, we blink with relief at our freedom, and the light of day, when he emerges into the street. Forget neutrality and a dry academic style; Charles Dickens has his own way of expressing his personal reactions and opinions, whilst convincing you that he is being objective.

Charles Dickens’s novelist’s eye comes through very clearly. His is no guide book to Italy, but an attempt to analyse the soul and character of Italy. He keenly observes human behaviour and conditions, and applies his skills of social criticism, just as he does throughout his novels. In some ways this work parallels his first book, “Sketches by Boz”, which described the social life and customs of England, but Pictures from Italy is a far more mature work, where Charles Dickens’s personal views and reactions are to the fore.

In his novels he also casts aspersions on travel writers, for their prescriptive tone. For instance, when they instruct the reader, you must visit this particular Art gallery, and take note of the works by a specific artist, but only in his later period—not his immature works. You must visit a certain city because it has a wonderful cathedral. If you are a cultured person then you must not miss this one, for its aesthetic beauty, especially noting the triptych on the North-West transept … and so on. Charles Dickens takes exception to what he considers pretentious claptrap, and mocks it mercilessly.

I do wonder what such Art critics and travel writers must have thought of his work in what they would consider “their” field. Perhaps they would have summarily dismissed it as not fit for (their) purpose. They would have been right. Charles Dickens could not write a dry, boring text book to save his life. Even at the the height of terror, or great emotion in his novels, he could never resist putting in a ridiculous image to make us smile. Disrespectful, ludicrous, inspired with awe, scathing or simply in a literary temper, this work is different from any other you will read.

Charles Dickens’s impressions of his journeys are exciting and full of thrills, allied with piercing social commentary. He was very much impressed by the vivacious street carnivals, the costumes, and effusive personalities of the Italians, and we share his enthusiasm. Just as in his novels, his descriptions are in parts hilarious, gruesome, exuberant, damning and sometimes discursive to the point of irrelevance, but they are always entertaining. Charles Dickens is here at his most judgemental—and his most persuasive. If he likes a place, you will wish you were there with him. If not, well then you will share his horror and indignation.

And the writing is sublime.