What do you think?

Rate this book

288 pages, Hardcover

First published February 22, 2019

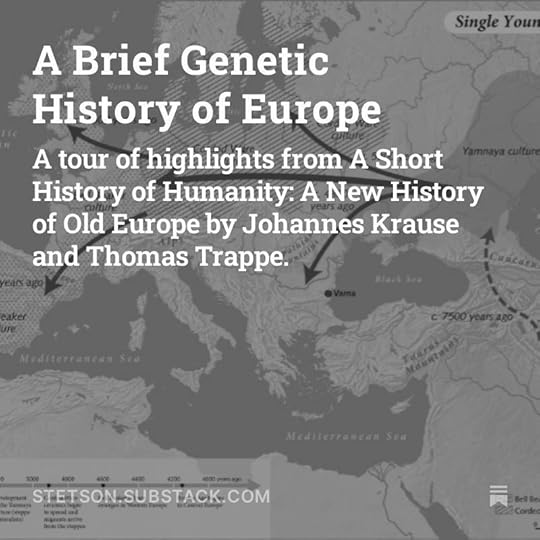

The oldest decoded plague genome dates from this period. It was found in the remains of people from the Yamnaya culture on the steppe, and spread into Europe along the same path as the steppe DNA.

Today’s Spaniards, like Sardinians, Greeks, and Albanians, have the fewest steppe genes of all Europeans.There is a chapter in the book that discusses what can be learned from spoken languages. Generally speaking the study of language differences and similarities provides indications of migrations that are parallel to those produced by DNA.

In 2014, we were able to confirm the diagnosis with genetic analyses of samples from the mummified bones. It was clear that TB had been rife in the Americas long before the arrival of Christopher Columbus, ... By comparing modern tuberculosis bacteria from across the world with pre-Columbian American pathogens, we were able to establish when and where their common ancestors existed: approximately 5,000 years ago somewhere in Africa. None of this fits with the idea that tuberculosis was brought to the Americas by humans 15,000 years ago. Five thousand years later the land bridge to Alaska was underwater, so tuberculosis could not possibly have come to the Americas that way, and certainly not in a cow, because we know that there were no cattle in the pre-Columbian Americas. …This second excerpt is about a mystery that has bothered me ever since I read the book 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed, by Eric H. Cline. Who were the "sea peoples" who caused the collapse of the Bronze Age? DNA analysis is beginning to answer some of the questions about the sea peoples.

What this tells us is that in the past millennia, TB must have taken different routes to the Americas and Europe than previously assumed. In the case of the Americas, we are now quite sure that it swam across from Africa. Pathogens similar to the bovine tuberculosis bacterium have since been found in other animals, including sheep, goats, lions, and wild cattle, but also in seals, and the strain found in seals was the most similar to the variant in the human mummies from Peru. In one of those animals, the bacterium must have found its way from Africa to South America by crossing the Atlantic. In some coastal regions of South America, seals were a popular source of human food, so their resident bacteria would have easily infected the local human population. Over the following millennia, tuberculosis spread across the whole of the Americas, probably evolving into an American variant of the disease. It was this strain that infected—and likely killed—the three mummified individuals in Peru. (p. 196-197)

In order to shed light on this 150-year period after the empires of the Near East collapsed, we examined the skeletons of people who lived in what is now Israel and Lebanon both before and after the crisis. We managed to obtain usable DNA from half a dozen individuals from three of the biblical Philistine settlements and saw a clear shift in the region’s DNA after the presumed arrival date of the sea peoples. A new genetic component from the south of Europe had been introduced. We can infer from this that the Philistines’ homeland may have been located in the Aegean, since the Mycenaeans living there had a similar genetic structure. At the start of this 150-year dark age, the Mycenaean civilization was among the first to crumble, just before raids by the sea peoples were reported in the empires farther east and south. In other words, the sea peoples do seem to have existed, and evidently they came from the area around the southern Mediterranean. The idea that they were Mycenaeans is only conjecture, however, because as yet we haven’t examined enough Mediterranean civilizations from the late Bronze Age to narrow down the origin of the Philistines more precisely. Theoretically, the seafarers’ new genetic component could have come from Cyprus or Sicily. As we don’t currently have enough sequenced genomes from these regions, we can’t rule them out. On the other hand, archaeological findings have suggested a connection between the Philistines and the Aegean. Our analysis revealed another surprise. We found almost no traces of the newly introduced southern Mediterranean DNA in individuals from those Philistine cities a few hundred years after their initial arrival, suggesting that those migrants did not keep to themselves over the following centuries; they rather admixed with the local population. We could not find any significant differences between the local Philistine and Caananite population by 800 BCE, debunking ideas of genetic separation between people from those different cultural groups during the Iron Age. Like everywhere else during this time, they were highly connected through trade and marriage. (p.153)