What do you think?

Rate this book

336 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2019

”He had lived sixty years on this earth and his memories had grown up around him like a garden, so that he now could walk among them and reach out a hand and crush their leaves in his fingers for the scent.”

”He had thought to write a novel in the manner of Joyce, a single twenty-four hour account of his astronomer great-grandfather during the landings of Garibaldi’s soldiers in May of 1860. His prince, Don Fabrizio, would observe uneasily the passing of his world, and his class, and the coming of the new Italy. A nephew, Tancredi, handsome, charming, changeable, would see his opportunity and fight alongside the redshirts.”

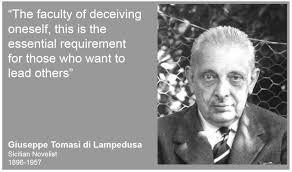

“This state of things won’t last; our lively new modern administration will change it all.” The Prince was depressed. “All this shouldn’t last; but it will, always; the human ‘always’ of course, a century, two centuries . . . and after that it will be different, but worse. We were the Leopards and Lions; those who’ll take our place will be little jackals, hyenas; and the whole lot of us, Leopards, jackals and sheep, we’ll all go on thinking ourselves the salt of the earth.” Don Fabrizio, 'The Leopard' by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa]

The past seemed a great flowing passage through which his bloodline passed, back through the wastrel grandfathers and great-grandfathers, to the saints and holy men of the eighteenth century, to the legendary civic figures of the seventeenth and the royal granting of Lampedusa in 1667 and the first Tomasi's wedding to the heiress of Palma, and deeper, back up the coast to Naples, to Capua, and further back to Siena, and then into the fog of an almost time, to Lepanto or Cyprus or the age of Tiberius in Rome. And he understood his great regret: after him would come nothing. He had produced neither son nor daughter. He had failed them all.

All summer as he had set down his pen and screwed the lid back onto his jar of ink and studied his hands he had seen the flesh of an old man, a failed man. Perhaps, he thought, art could not be created without the failings of its maker. Perhaps it was the very weakness of the writer that made the writing human, and therefore moving, and therefore worth preserving. He had understood for a long time that the world was greater by far than anything he could offer it, and that what he had most longed for, the creation of something to outlive him, a testament in his own hand, would most likely fail in the end. But what he had not understood before was how the strain of the attempt constituted the greater labour. Which, he supposed, as the evenings had lightened in the curtains of his study, was not so very different from the labour of living itself.

His gaze would pass first over the dark entrance of a street he knew too well, and it was here that the old quarter lost its beauty for him and became something other than a part of an ancient city on a quiet coastline of Sicily. For Via Valverde opened onto Via di Lampedusa, and he knew that there lay the crumbling plaster and stone of his beloved palazzo, where his mother had lived out her final years, thin, sullen, solitary, a faint reflection of the dazzling creature she had once been, where she had been discovered dead one morning in a ruined armchair in the bombed-out library, under an open sky, one more casualty of a war that had been ended for two years already and yet would not ever end, having destroyed both the past and the future and leaving in the present nothing but devastation and grief.

Du stellst dir immer vor, dass alles besser wird, sagte er jetzt.

Sie sah ihn überrascht an. Wird es ja auch, erwiderte sie.

Du bist eine Optimistin. Hätte ich das gewusst, hätte ich dich nie geheiratet.

Auch du bist voller Hoffnung, mein Schatz, sagte sie. Deshalb bist du traurig.