What do you think?

Rate this book

272 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1928

Peaceful little one, standest thou yet? cool nook, earthly paradisal cupboard with leaf-green light to see poetry by, I fear much that 1918 was the ruin of thee. For my refreshment, one night's sound sleep, I'll call thee friend, ‘not inanimate’…

I suddenly remembered, here, that midnight had passed, and this was my twenty-first birthday.

by

by

Robert Graves

Robert Graves by

by

Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Sassoon

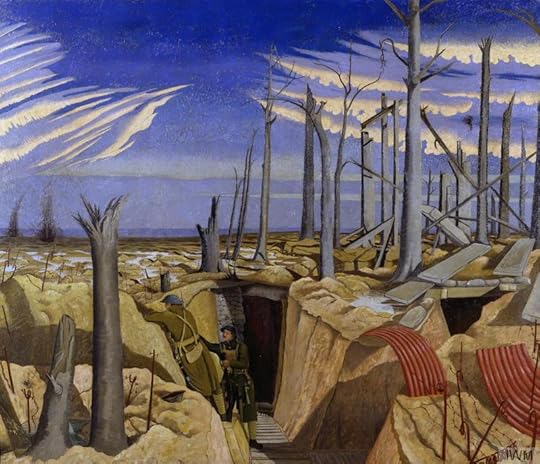

It was Geoffrey Salter speaking out firmly in the darkness. Stuff Trench - this was Stuff Trench; three feet deep, corpses under foot, corpses on the parapet. He told us, while still shell after shell slipped in crescendo wailing into the vibrating ground, that his brother had been killed, and he had buried him; Ivens - poor "I won't bloody well have it sergeant-major" Ivens - was killed; Doogan had been wounded, gone downstairs into one of the dugout shafts after hours of sweat, and a shell had come downstairs to finish him; " and," says he, "you can get a marvellous view of Grandcourt from this trench. We've been looking at it all day. Where's these men? Let me put 'em into the posts. No, you wait a bit, I'll see to it. That the sergeant-major?"