What do you think?

Rate this book

352 pages, ebook

First published December 1, 2019

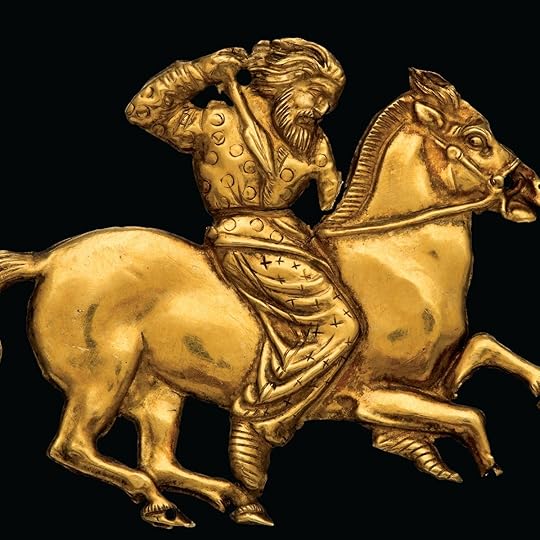

Scythian rider wearing vibrant red tight-belted coat and trouser, visibly holding his battle-axe and wearing akinakes (a type of short-sword) on his waist. Painting by Evgeny Kray based on the archaeological finding of Pazyryk kurgan.

“We shall do well to heed Sir John Boardman's warning: ‘We think we know a lot about Scythian life, but most comes through Greek eyes and texts. The Greek-style finds and Herodotus are given prominence, but the majority of the sites and tombs tell a different story, of a people immune to most Mediterranean ways of life and probably more likely to exploit than be exploited by the newcomers from the south.’” ~Introducing the Scythians: Herodotus on Koumiss research paper, page 85, by Stephanie West.

Artistic representation of the Scythians. Both men wore richly embroidered tight-belted coats and they’re adorned with golden jewellery. A gorytos (leather bow case) is slung on the first man’s waist and the other holds an akinakes (short sword).

“The Roxolani (one of the Sarmatian tribes), now dominant on the Pontic steppe, were described as ‘wagon dwellers’ by Strabo. He writes of their transhumant lifestyle, dependent on their flocks and herds, moving from winter camps along the shore of the Sea of Above, where in their leisure time they hunted deer and wild boar, to the inland steppe pastures, where they turned their attention to wild asses and roe deer. But in spite of this bucolic lifestyle they were a force to be reckoned with.” ~Chapter 12: Scythians in the Longue Durée, page 319.

“In the Indo-Iranian tradition the king had charisma (farnah-) which materialised in the form of gold, the royal metal. Thus in controlling the sacred golden objects the king was displaying the outward and visible signs of his extraordinary powers.” ~Chapter 10: Of Gods, Beliefs, and Art, page 272.

“The love of gold, the use of inset turquoise, and motifs of fabulous beasts are all characteristics strongly reminiscent of Sakā burials in the Kazakh steppe.” ~Chapter 12: Scythians in the Longue Durée, page 315.

“From the Scythians, the Hellenes mainly purchased grain, for which there was a great demand in Greece. Another object of trade were Scythian slaves, whose presence in cities such as Athens is confirmed extensively in Greek literature of the classical era (5th–4th century BCE). It cannot be ruled out that the Hellenes also purchased traditional nomadic products (milk, animal skins, horses, cattle, etc.). Among the Scythians, and among many other nomadic peoples, luxury goods produced in Greek craftsmen’s workshops were highly prized. Judging by the content of the graves of the Scythian aristocracy, articles produced by Greek goldsmiths were particularly popular.” ~Black Sea-Caspian Steppe, part of The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe book by Aleksander Paroń.

Greek depictions of Scythian archer on Attic pottery (sixth century BCE).

“The skull of a particularly detested enemy, such as a relative killed in a feud, might be turned into a drinking cup. ‘Having sawn off the part below the eyebrows and cleaned out the inside, the cover the outside with leather.’ A rich man would also line the inside with gold. On the occasions when the cup was being handed round to prestigious visitors stories would have been told of the exploits which led to its creation. Here the intention seems to have been to insult the memory of the deceased and induce the visitors to share in the insult. The veracity of Herodotus’ description of skull cups is shown by the discovery of a workshop specialising in skull cup production in the fortified settlement of Bel’sk. In 529, when the Sakā queen, Tomyris, defeated the persian leader, Cyrus, in battle, it is said that she took his head as a trophy.” ~Chapter 9: Bending the Bow, page 262.