What do you think?

Rate this book

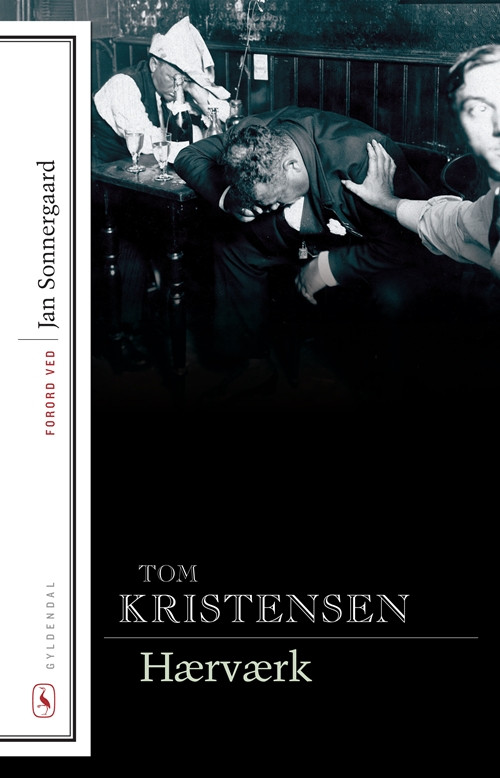

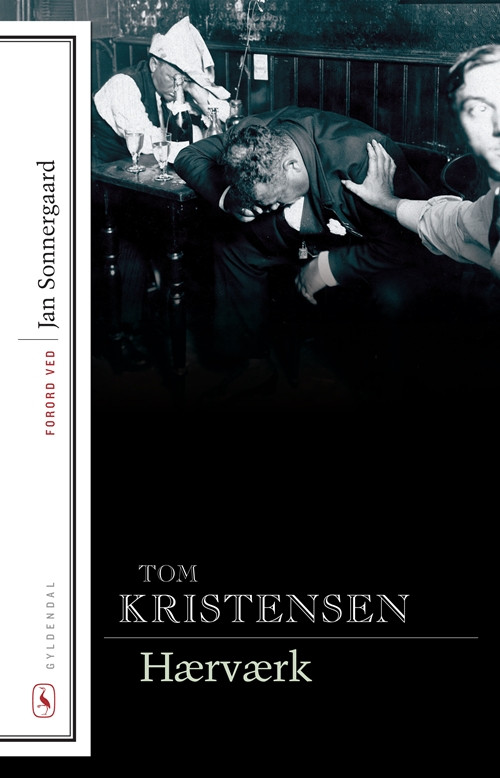

571 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1930

”¡De profundis clamavi!”La novela se lee con la sensación persistente del que está viendo una película de terror en la que el estúpido personaje, haciendo oídos sordos a todas nuestras advertencias, se va encaminando hacia la puerta con la intención de abrirla. ¡No la abras, no abras esa maldita puertaaaaaa¡, nos desgañitamos inútilmente: el personaje, obviamente, abre la puerta y… Bien, pues así nos las tenemos que ver, aunque sin sombra alguna de la intensidad que ponemos ante el tipo de la puerta, durante más de seiscientas páginas con Ole Jastrau, un pobre hombre con una juventud políticamente rebelde y con ínfulas de poeta que a su mediana edad se ve encerrado en una vida burguesa y acomodada que lo va secando poco a poco mientras él se va mojando en alcohol de mucho en mucho. De nada sirve que nos desgañitemos mentalmente, Ole Jastrau va tomando en cada momento la opción que justamente más le perjudica, aunque quizá sea también la única opción que puede soportar, la que le acerca un poquito más a la devastación buscada.

”¡Oh, allí no había vacío! ¡Vida! ¡Vida!... Sumérgete en whisky y cree en tus amigos.”Nada se le puede decir a Jastrau, no serían más que “voces desde la orilla mientras él pasa flotando a la deriva”. Su familia, su trabajo, su vida entera, la que siente como una traición a todos sus principios, se va escabullendo poco a poco en una lenta espiral degradante alrededor del desagüe que, como un agujero negro, terminará por atraerlo y absorberlo sin mucha resistencia por su parte. Jastrau es de esas personas que arrojan sobre sus espaldas todas las culpas de la humanidad y por las que, como la figura de Jesucristo con la cual se identifica a menudo, no descansará hasta obtener su castigo.

“Sí, beber hasta perder el juicio tenía algo de religioso. La sensación de vacío se desvanecía. El espacio se colmaba de un yo ruidoso, balbuciente y borracho, todo el espacio.”El atractivo de ese fondo del pozo al que se dirige activamente radica en el sentimiento de invulnerabilidad, no tener ya nada que temer, y, sobre todo, no tener que ceder más para mantener esa vida burguesa que desprecia tan intensamente y para la que no encuentra alternativa posible más allá del próximo vaso de whisky.

“Nunca he visto una anémona azul… necesito sacarme de la cabeza esta asquerosa anémona azul, la muy maldita.”Todo esto suena muy bien, al menos para un lector como yo. Hasta tiene alguna que otra pincelada de humor:

“—La vida es la mayor canallada con la que me he topado, qué vergüenza que Goethe jamás escribiera una palabra al respecto.Y sin embargo, a pesar de todo ese interesante camino hacia la devastación personal, uno lee las seiscientas cincuenta páginas con una aburrida indiferencia. El estilo de Kristensen es frío, su ritmo, lento, las escenas, repetitivas (quizás un homenaje al eterno retorno de Nietzsche, citado en la novela) … En fin, otro libro en el que la letra es estupenda pero la música no es capaz de resaltarla como convendría.

—Sí, es para volverse loco… La cantidad de cosas que Goethe no escribió.”

“Hay que construir un lenguaje nuevo… El lenguaje es una furcia, sí, señor. El ser humano jamás debería haberse liado con ella. No debería haber aprendido a hablar, no. Eso ha destruido la vida… esas estúpidas palabras cierran el camino hacia el infinito”

I have longed for shipwrecks,

For havoc and sudden death.”

"في زماننا قد يُولَد قدّيسٌ واحدٌ كلَ مئة عام، بينما يو لدُ آثمو ن كلَ ثانية، نحن لسنا قلّة ".

- توم كريستينسن