What do you think?

Rate this book

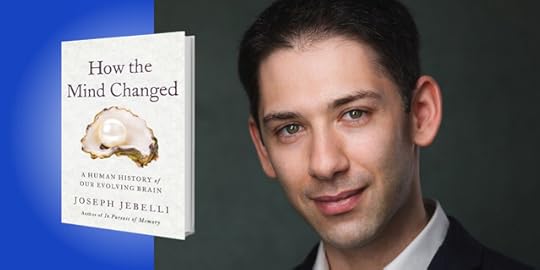

320 pages, Hardcover

Published July 12, 2022

Researchers have found that ancient cave art is often located in acoustic hot spots: spaces where sound generates echoes. These cave chambers are harder to reach than chambers that have no echo, so it’s thought they were deliberately chosen as places for secretive rituals and dramatic storytelling.Maybe these chambers that are harder to reach were chosen because they were safer? Maybe the art is a product of being in them for a while and having nothing better to do? Are the 'quiet chambers' easier to access, it seems so but the author doesn't say, if so maybe the people weren't in them very long compared to the safety of the hard to access ones?

Strikingly, when acoustic archaeologists study the sonic properties of these caves, they find that paintings of cloven animals such as bulls, bison and deer, appear in chambers that generate echoes and reverberations that actually sound like hoof beats. Quiet chambers, on the other hand, are painted with dots and handprints.

Simply put, it states that humans need large brains to manage their remarkably complex social systems. However, there is a constraint on the number of individuals a person can maintain a stable relationship with, which Dunbar calculates to be about 150 people – Dunbar’s number, otherwise known as a ‘clan’.I wonder if that is true or not of Goodreads, I can't believe myself it is true of FB, Twitter or anything else surveyed without any bias.

It turns out that a striking number of human organisations from factories to villages to armies operate around units of about 150 people. And the vast majority of Facebook users list around 150 friends.

These growing brains would then explain many of the behavioral changes across the Pleistocene. Hunters of small, fleet prey may have needed to develop language and complex social structures to successfully communicate the location of prey and coordinate tracking it.So this hypothesis is that social structures grew as a result of bigger brains, rather than the author saying that brains grew bigger because of social interaction.

"...When we think of minds changing we usually think of psychological changes that affect our moods and outlook. Or neurological changes following a head injury or during an illness. But the changes I am interested in run much deeper. They span the evolutionary history of our early human ancestors and shape every aspect of who we are – our emotions, our memories, our languages, our intelligence and, indeed, the very fabric of our cultures and societies. It might not feel like it, but we are all heirs to millions of years of brain evolution: countless trial-and-error experiments in our mind’s relationship with the natural world. As a result, we are cleverer and more interconnected than our forebears ever imagined."

"Scholars in the new field of discursive psychology, a branch of science that investigates how the self is socially constructed, are particularly interested in how people’s pronouns affect their sense of self. According to these scholars, the self is a ‘continuous production’ built from words and culture. Until recently, the first-person pronouns ‘I’, ‘me’ and ‘mine’ predominated in Western society. Now, however, dozens of pronouns are used to express various identities: ‘ze’, ‘ey’, ‘hir’, ‘xe’, ‘hen’, ‘ve’, ‘ne’, ‘per’, ‘thon’ and more. Sticklers for grammar view this as an assault on the English language. Sticklers for tradition view it as a slippery slope to government-mandated speech codes.

Yet far from being new-age gobbledygook or an omen of tyranny, novel pronouns in fact have a crucial social function. They reveal your personality, reflect important differences among groups and help knit communities together."

"Even today, the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnosis and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the DSM-IV, defines autism as a condition manifesting in an ‘abnormal development in social interaction and communication, and a markedly restricted repertoire of activity and interests.’ But I am reluctant to accept the words of a psychiatric organisation that as recently as 1968 defined homosexuality as ‘a mental disorder’."

"Conventional wisdom suggests that seeing the bear triggers a feeling of fear, which in turn causes the surge of adrenalin our body needs to fight or flee. But this is actually the reverse of what happens. The truth is that when we see the bear, our body instantly responds — blood pressure rises, pulse rate increases, respiration quickens — and because of these physiological changes we feel afraid. The emotion arises at the end of the sequence, not the beginning. It is merely the perception of change. "

"Common sense says we lose our fortune, are sorry and weep; we meet a bear, are frightened and run; we are insulted by a rival, are angry and strike... the more rational statement is that we feel sorry because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble. "

"My body was feeling happy, because I felt a rush, a flutter, as if blood was coursing through my veins, trying to tell me, 'this is joy'. It might sound strange, but I think emotions aren't really made in the brain; they're interpreted there. Predicted, maybe. "

"We construct emotions all the time. We are not born with them. They are not hardwired into the brain. When we think about that upcoming exam, or desire someone else's possessions, or bump into an old flame, the emotions of anxiety, envy and love can appear and then disappear automatically. They are as fleeting and ephemeral as memory — and as equally dependent on the times. Just compare how we feel about the environment and gender roles today with how we felt about them only a few decades ago. We create emotions. The brain invents them, moment to moment, to make sense of an ever-changing world.

[...]

Evolution still had to build the amygdala and Other neurological hardware to let us experience different emotions. To separate the biology of emotions from the cultures that influence them would be like separating the tides from the sea. "

"Different cultures create their own emotional language. [...] It is our societies shaping our emotions, rather than our emotions shaping our societies. We are reacting to society, not simply feeling in a void. The societies we build have an extraordinary influence on how we feel and experience the world"

"The second possibility is that depression is an adaptation that evolved in response to complex problems, and is our brain's way of telling us to stop and solve these problems. Research shows that depressed people are often highly analytical: they think intensely about their problems and are usually unable to think about anything else. Viewed this way, the sufferer's indifference to everything from house- cleaning to socialising to simply staying awake is instead the brain redirecting energy in order to ruminate on an important problem that has become unbearably difficult to resolve, such as a failing relationship or a struggling business. The psychologist Lauren Alloy calls this ability 'depressive realism'. "

"Though it might sound a little far-fetched, geneticists are now finding that many of the genes that increase one's risk of depression also boost the brain's immune response to infection. Among them is a gene called NYP, which codes for one of the most abundant proteins in the brain: a neurotransmitter known as neuropeptide Y. Normally NYP kills infectious agents by unleashing the brain's inflammatory response, a powerful yet short-lived measure that must be tightly controlled "

"Depression forces us into a kind of social hibernation, much like the self-imposed hibernation we go through when unwell, and this would have allowed our ancestors to conserve the energy necessary to fight off an infection, as well as reducing their chances of being infected by something else. The theory also helps explain the extended duration and diversity of depression's symptoms — because infections can last a long time and are becoming increasingly diverse themselves. With this radical new approach to depression, Bullmore writes, 'we can move on from the old polarised view of depression as all in the mind or all in the brain to see it as rooted also in the body; to see depression instead as a response of the whole organism or human self to the challenges of survival in a hostile world.'"

"Many scientists argue that memories are physically encoded in the brain by a network of neurons in the hippocampus and cortex. The fundamental idea is that you have an experience — say, you lose your virginity — and a memory of the experience is sent to the hippocampus in the form of electrical signals travelling across synapses. The memory may then reside in the cortex as long-term memory, or it may not. 'That depends on complex molecular processes involving neurotransmitter receptors, enzymes, genes, epigenetics, and so on. Until recently this idea was mainstream neuroscience.

The language that scientists use to describe memory — 'memory' retrieval', 'memory acquisition', 'memory trace', 'memory consolidation' and so on presupposes the notion of 'a memory', something that is separate from the person doing the remembering. Do you see the problem? The language defines memory as separate from the mind instead of an integral part of it; when the truth is, your brain doesn't store or retrieve memories. It is memories. "