What do you think?

Rate this book

208 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1940

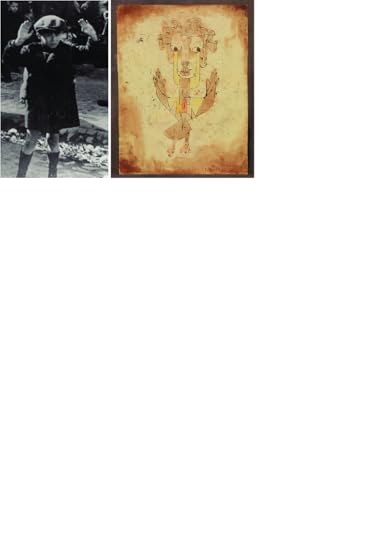

“A Klee painting named ‘Angelus Novus’ shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such a violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”

"Sinasabing may automaton na nakakasagot sa bawat kilos ng manlalaro ng chess upang ito ang tiyak na mananalo sa laro. May papet na nakasuot ng damit Turko at mga shisha sa bibig na nakaupo sa harapan ng board na nakapatong sa isang malaking mesa. Lumilikha ang isang sistema ng mga salamin ng ilusyon na walang nakaharang sa ilalim ng mesa mula sa lahat ng panig. Sa katunaya'y may maestro ng chess na kubang pandak sa loob na ginagalaw ang kamay ng papet sa pamamagitan ng tali. May maiisip ng katumbas sa pilosopiya ang aparatong ito. Lagi raw mananalo ang papet na binansagang "materyalismong istoriko." Mula rito'y madali na lamang talunin ang kahit sinumang basta kinuhang tagasilbi ng teolohiya na sa kasalukuya'y maliit at pangit at talaga namang hindi dapat ipakita."There are nineteen others like this and they deal with history, philosophy, sociology, religion, etc. They seem to be very interesting and if I only have time, I would google each term and people mentioned in the book plus the ones in Wiki. However, suffice it to say that this book is worth reading and pondering if you are into history and philosophy.

“Historicism [….] dominates the ideas of authors as diverse as Lukács, Korsch, Gramsci […] Sartre. It is characterized by a linear view of time [….] The knowledge of history is then the self-consciousness of each present [….] class consciousness [….] the organic ideology of the ruling (hegemonic) class [….] Human intersubjectivity as a whole, human ‘praxis’ […]” (L. Althusser, Glossary in: Reading Capital 1968, p.351, Verso, 2009)In other words, still an idealist conception of history, despite even deriving that primacy of investigation of consciousness from an economic-base:

“Historicism justifiably culminates in universal history. Nowhere does the materialist writing of history distance itself from it more clearly than in terms of method. The former [Historicism?] has no theoretical armature. Its method is additive: it offers a mass of facts, in order to fill up a homogenous and empty time. The materialist writing of history for its part is based on a constructive principle. Thinking involves not only the movement of thoughts but also their zero-hour [….] The historical materialist approaches a historical object solely and alone where he encounters it as a monad.” (W. Benjamin, On the Concept of History 1940, p.20, Classic Books America, 2009)Anyway, in the science of history, the primary historical-material is not just a mass of raw-data and facts, but an economic-dialectic. History is usually taught (or thought of) as a list of facts of historical-material to memorize, such may be the content (or events taking place) in history, but more important is the logic of history, the self-moving cell (production, class-struggle, or work and fight) which powers the totality, universal to all economic modes of production versus the particular developments to each historical-era:

“Hitherto, sociologists had found it difficult to distinguish the important and the unimportant in the complex network of social phenomena (that is the root of subjectivism in sociology) and had been unable to discover any objective criterion for such a demarcation. Materialism provided an absolutely objective criterion by singling out production relations as the structure of society, and by making it possible to apply to these relations that general scientific criterion of recurrence whose applicability to sociology the subjectivists denied. So long as they confined themselves to ideological social relations (i.e., those which before taking shape, pass through man’s consciousness) they were unable to note the recurrence and regularity in the social phenomena of the various countries, and their science was at best only a description of these phenomena, a collection of raw material.” (V. I. Lenin, What the ‘Friends of the People’ are and how they fight the Social-Democrats 1894, p.12, FLP, Peking, 1978)The specific content, events of history, are to an extent recurring, if the former is the case, then, all that is left is to explain the inner-economic-logic, or laws which govern the direction, goal, outcome, (end) of that history, for which a structure of change emerges. In this sense, the science of history may even eliminate those specific contents of history, seeing waves, cycles and spirals if left only to abstractions without any relation to concrete technological-developments, and their subjective implementation. People always ask for the following, an account of history so precise we may as well be attempting to raise the dead:

“The chronicler who recounts events without distinguishing between the great and small [….] only for a resurrected humanity would its past, in each of its moments, be citable. Each of its lived moments becomes a citation […]” (W. Benjamin, p.4)The science of history is entirely partisan for the revolutionary subjects of history, the socially necessary labourers, in recognizing their work and fight as a force of positive change for which their knowledge is transferred. To claim the science of history is a positivist ‘distanced observer’ mistakes the opposite of the science of history for the science of history! This ‘concept’ of history then reflects the totality of essential and inessential viewpoints, without prioritizing (or only giving a notion of) the essential alone which is necessary in description of the inner-laws which govern the objective-process. At first, there may be an all-sided analysis of each class in the class-struggle, but the point is, in the final analysis, primarily, partisanship towards the catalyst of production and technological advance, socially necessary labour, or the classes who are the revolutionary subjects of history:

“Fustel de Coulanges recommended to the historian, that if he wished to reexperience an epoch, he should remove everything he knows about the later course of history from his head. There is no better way of characterizing the method with which historical materialism has broken. It is a procedure of empathy. Its origin is the heaviness at heart, the acedia, which despairs of mastering the genuine historical picture, which so fleetingly flashes by [….] Few people can guess how despondent one has to be in order to resuscitate Carthage [….]” (W. Benjamin, p.8)

“To articulate what is past does not mean to recognize ‘how it really was.’ It means to take control of a memory, as it flashes in a moment of danger. For historical materialism it is a question of holding fast to a picture of the past […] ” (W. Benjamin, p.7)

“In the historical materialist they have to reckon with a distanced observer [nonsense] …. the cultural heritage [….] It owes its existence not only to the toil of the great geniuses, who created it, but also to the nameless drudgery of its contemporaries. There has never been a document of culture, which is not simultaneously one of barbarism. And just as it is itself not free from barbarism, neither is it free from the process of transmission, in which it falls from one set of hands into another. The historical materialist thus moves as far away from this as measurably possible. He regards it as his task to brush history against the grain.” (W. Benjamin, p.8)

“Every child knows that a nation which ceased to work, I will not say for a year, but even for a few weeks, would perish.” (Marx to L. Kugelmann, July 11, 1868, In: K. Marx, F. Engels, Selected Letters, p.33, FLP, Peking, 1977)The science of history does not crudely collapse subject and object (spirit and nature), into a spontaneously-materialist or positivist absolute-substance (eliminating the subject), but rather affirms the subject to be reflected from and dependent upon-and as a result reactive later, on the object. There is no objectivist, positivist, pure, neutral third, ‘absolute subject’, ‘distanced observer’ standing above overseeing all history with a so-called timeless-morality, existing outside the world, disaffected by sin, negativity and historical-economic necessity, denying motion with total indifference to everything:

“The puppet [wow!] called ‘historical materialism’ is always supposed to win. It can do this with no further ado against any opponent, so long as it employs the services of theology […]” (W. Benjamin, p.2)Our ideas may very well just be a reflection of the real (the refraction of an economic-class in the prism of the process of production) so theology can also be considered an ‘organic’ reflex of society itself:

“man, turning against the existence of God, turns against his own religiosity.” (K. Marx, F. Engels, The Holy Family 1845, p.110, FLP, Paris, 2022)Hence, to turn against theology in a religious-society is to turn against society itself - our own selves. But if society has turned against religion, turning to a theology which is alienated from life, confronting society, is then to turn against society which has changed its economic habits and practices. So long as in real-life we are estranged from, and confronted by that real-life (i.e. creating a world which we do not willfully create, but for a wage to eat bread) philosophy, theology, scientific-abstractions, university discourse, bourgeois ideology → alienated-thought will persist:

“The production of ideas, of conceptions, of consciousness, is at first directly interwoven with the material activity and the material intercourse of men, the language of real life. Conceiving, thinking, the mental intercourse of men, appear at this stage as the direct efflux of their material behavior [….] In direct contrast to German philosophy which descends from heaven to earth, here we ascend from earth to heaven [….] We set out from real, active men, and on the basis of their real life-process we demonstrate the development of the ideological reflexes and echoes of this life-process. The phantoms formed in the human brain are also, necessarily, sublimates of their material life-process, which is empirically verifiable and bound to material premises [….] men, not in any fantastic isolation or abstract definition, but in their actual, empirically perceptible process of development under definite conditions. As soon as this active life-process is described, history ceases to be a collection of dead facts as it is with the empiricists (themselves still abstract), or an imagined activity of imagined subjects, as with the idealists. Where speculation ends—in real life—there, real, positive science begins: the representation of the practical activity, of the practical process of development of men. Empty talk about consciousness ceases, and real knowledge has to take its place. When reality is depicted, philosophy as an independent branch of activity loses its medium of existence.” (K. Marx, F. Engels, The Germany Ideology 1845, p.13-14, FLP, Paris, 2022)In this sense, we can say that philosophy is over and science has begun, only if we mean that the problems of the old philosophy have been solved, that is, when the idea corresponds to the real, when being asserts its primacy over thought, or when the historical-material recorded is a description of the real and not of the ideal. However, an end of philosophy (alienated-thought), then assumes an end of the history of alienated-being. As soon as truth is identified with reality (which mediates knowledge), philosophy as alienated-thought, a reflection of alienated-being, begins its end. When humans in the world are no longer alienated, so to, ends alienated-thought (philosophy). Philosophers writing about knowledge, may make systems of knowledge, noting down alienated-thought, but this is not the same as the process of being (becoming) which acquires knowledge: real-life processes, life-activity, economic-relations. Such is where a science of history is possible to begin:

“the science of the history of society, despite all the complexity of the phenomena of social life, can become as precise a science as, let us say, biology, and capable of making use of the laws of development of society for practical purposes. Hence, the party of the proletariat should not guide itself in its practical activity by casual motives, but by the laws of development of society, and by practical deductions from these laws. Hence, socialism is converted from a dream of a better future for humanity into a science.” (J. Stalin, Dialectical and Historical Materialism 1938, p.23, FLPH, Moscow, 1951)Of course, the economic-laws of the macro-societal world are in no way any less scientific than the so-called “eternal” laws of the biological micro-world (observed from some microscope or telescopic apparatus), as if the abstractions drawn from under a microscope are any more scientific than the relational-abstractions extrapolated from the economy:

“The laws of the microworld are paradoxical from the standpoint of conventional macroscopic conceptions […]” (M. E. Omelyanovsky, Dialectics in Modern Physics 1973, p.19, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1979)And so, we have ended with the beginning, with the banishing various phantasms from the study of history. Beginning with the end, and ending with the beginning, the beginning also defines the end (another word for the end is direction, outcome, goal, objective, purpose, etc. immediately, a law governed process of economic-development, from the simple to the complex, comes to mind):

“the end is the beginning and the beginning the end. The content is thus a circle; it is the discovery of the self in the other extreme [...]” (L. Althusser, On Content in the Thought of G W F Hegel 1947, in: The Spectre of Hegel Early Writings, p.56, Verso, 2014)

"...expecting a meeting with past generations, we may suddenly realize that the response to our wait is us, ourselves; we understand that those awaited were – are – ourselves. This is how the look ‘backwards,’ to where we suppose that that ‘other’ generation – that of the past – exists, reveals itself to be a look ‘forwards,’ towards the future generation: that is, towards the present generation in which we ourselves, the contemporaries, live. The ‘others’ – those of the past and those of the future – suddenly coincide in ‘us,’ those of now. This is the moment in which the rotating gaze of the Angel of History has captured us and has detained us in now-time."