What do you think?

Rate this book

A fascinating look at key thinkers throughout history who have shaped public perception of science and the role of authority.

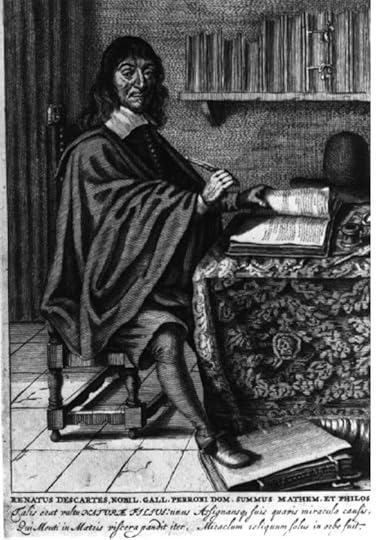

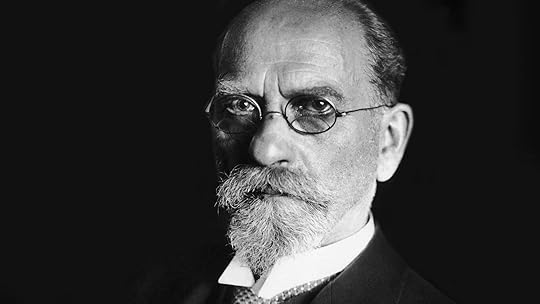

When does a scientific discovery become accepted fact? Why have scientific facts become easy to deny? And what can we do about it? In The Workshop and the World, philosopher and science historian Robert P. Crease answers these questions by describing the origins of our scientific infrastructure—the “workshop”—and the role of ten of the world’s greatest thinkers in shaping it. At a time when the Catholic Church assumed total authority, Francis Bacon, Galileo Galilei, and René Descartes were the first to articulate the worldly authority of science, while writers such as Mary Shelley and Auguste Comte told cautionary tales of divorcing science from the humanities. The provocative leaders and thinkers Kemal Atatürk and Hannah Arendt addressed the relationship between the scientific community and the public in in times of deep distrust.

As today’s politicians and government officials increasingly accuse scientists of dishonesty, conspiracy, and even hoaxes, engaged citizens can’t help but wonder how we got to this level of distrust and how we can emerge from it. This book tells dramatic stories of individuals who confronted fierce opposition—and sometimes risked their lives—in describing the proper authority of science, and it examines how ignorance and misuse of science constitute the preeminent threat to human life and culture. An essential, timely exploration of what it means to practice science for the common good as well as the danger of political action divorced from science, The Workshop and the World helps us understand both the origins of our current moment of great anti-science rhetoric and what we can do to help keep the modern world from falling apart.

592 pages, Kindle Edition

First published March 26, 2019

The very gears that make Facebook socially wonderful—its ease of connecting and sharing—are the same ones that facilitate trolling, the flourishing of hate groups, the dissemination of fake news, and dirty political tricks. In a similar way, the gears that make science work—the fact that it is done by collectives, is abstract, and always open to revision--also provide fuel for science deniers…The chapters that follow will explain how the current state of affairs came about, and what will be necessary to change it. Aristotle, one of the most practical and wise of all philosophers, wrote that, while it is easy to become angry, it is harder to be angry “with the right person, and to the right degree, and at the right time, and for the right purpose, and in the right way.” This book is about how to get angry about science denial in the right way.

Factual truth is essential to the public space and the ability to act. “Freedom of opinion is a farce unless factual information is guaranteed and the facts themselves are not in dispute.” She concludes: “Conceptually, we may call truth what we cannot change; metaphorically, it is the ground on which we stand and the sky that stretches above us.” To threaten facts is to threaten human existence, and freedom itself.

US politicians who attack science are like the Islamic State militants who bulldozed archaeological treasures and smash statues. Is such a comparison really over the top? Science is a cornerstone of Western culture, not only to ward off threats but also to achieve social goals. In seeking to destroy those tools science deniers are like ISIS militants in that they���re motivated by higher authority, believe mainstream culture threatens their beliefs, and want to destroy the means by which that mainstream culture survives and flourishes, If anything, ISIS militants are more honest, for they openly admit that their motive is faith and ideology, while Washington’s cultural vandals do not. It’s disingenuousness, prevents honest discussion of the issues, and falsely discredits and damages American institutions. At debates and press conferences, such politicians should be asked: “Explain the difference between ISIS religious extremists who attack cultural treasures and politicians who attack scientific process.” How they respond will reveal much about their values and integrity.